Regenerative Container Gardening

Building “Living Soil” in Pots & Planters

Container gardening can be deceptive, but we think we’ve found a way to make it work.

In June, everything looks perfect. The plants are small, the weather is mild, and the system works. But somewhere around the first week of August, the dynamic changes. You walk out to the patio and find your tomato plant wilting, even though the soil is damp. You water it, assuming it’s thirsty. The next day, the leaves turn yellow and the plant stalls.

The standard advice—small pots, gravel for drainage, and chemical fertilizer—sets up a cycle that breaks exactly when the summer heat peaks. The physics of a 5-gallon bucket simply cannot handle the energy load of an August afternoon.

For years, we assumed this was just the price you paid for gardening in a pot or container. We knew the standard “best practices”—we used shade cloth, heavy mulch, and drip irrigation—but even with those defenses in place, we felt like something was missing. It felt like we were fighting the environment rather than working with it.

We wanted more than survival—both for ourselves and for our customers who rely on our advice. We wanted resilience. We wanted the same nutrient-dense, self-regulating soil web we had in our raised beds, but in a smaller footprint that was easier on our backs.

To get there, we realized we needed to shift our focus toward regenerative container gardening. We had to look at our containers through a totally different lens.

This reality led us to ask a hard question: Is it possible to build a true “living soil” ecosystem in a container garden?

We wanted to know if a pot could function like a real ecosystem—maintaining its own soil moisture and cycling its own nutrients—or if being cut off from the Earth made that impossible.

We found that the answer is a qualified YES, and we are going to show you exactly how to succeed with regenerative container gardening.

When we looked for a guide on the physics of container soil, we came up empty. Most advice simply treats a pot like a smaller version of a garden bed. But no one seemed to be talking about the unique climate inside that box.

So, we had to go back to our sources. We dug into agricultural hydrology papers and soil physics textbooks—the dense stuff—to find out why these failures happen.

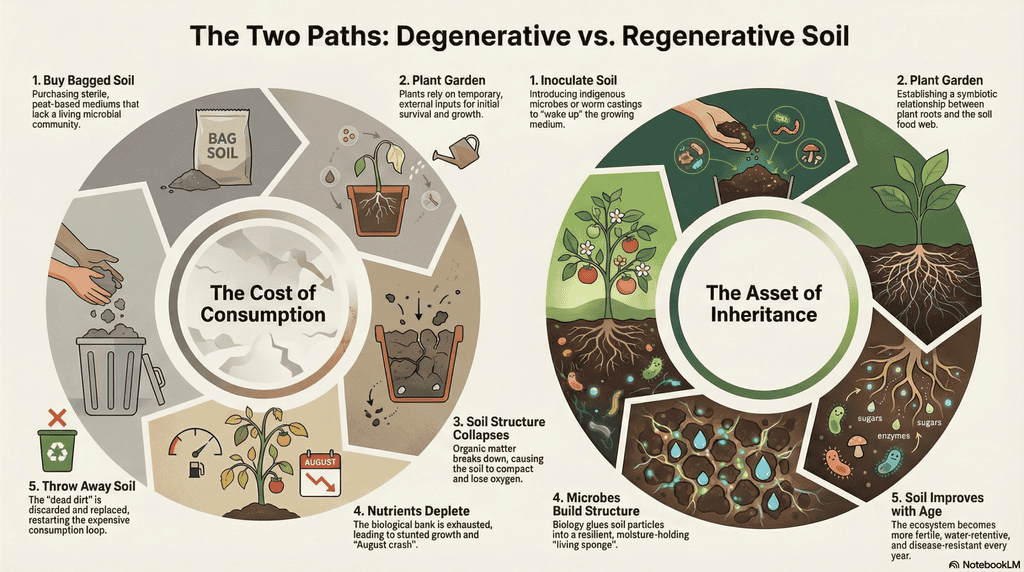

The Two Paths: Standard gardening consumes soil (Degenerative). Our method builds it (Regenerative). You stop buying dirt and start building a biological asset that improves every year.

The Definition

Organic vs. Regenerative

Before we get into the engineering, we need to clarify our terms. “Regenerative” is often treated as an agricultural buzzword for giant farms, and to most home gardeners, it sounds like a fancy word for “Organic”, but it applies to your container garden, too. But there is a critical difference.

- Organic is defined by what you don’t use (No chemicals, no pesticides).

Sustainable means keeping things the same. You put energy in, you get energy out. You maintain the status quo.

Regenerative is defined by what you build (Better soil every year).

In a standard container garden, the soil gets worse every year. It runs out of nutrients, collapses in structure, and eventually, you have to throw it away and buy new bags. That is a degenerative cycle.

In a regenerative container, the soil should be better in Year 5 than it was in Year 1. Because you are building a living food web—a biological engine—your soil becomes more fertile, more water-retentive, and more disease-resistant the longer you use it. You stop buying dirt and start building an inheritance.

The New Laboratory: Our transition from 24-foot in-ground beds to waist-high horse troughs. We moved to save our backs, but quickly realized we needed to engineer these new micro-climates to save our soil.

From Raised Beds

to Horse Trough Containers

A few seasons ago, Cindy and I made a decision that many of you are likely facing right now. Whether you are working with a shrinking backyard, moving to a patio, or—like us—simply deciding it is time to save your back, the challenge is the same: How do you keep growing when your physical footprint gets smaller?

After almost three decades of gardening in twenty-plus 24-foot raised beds, we knew we didn’t want to stop growing—that isn’t in our DNA. But we needed to change how we grew. We relocated our entire garden into a collection of large, horse watering troughs raised to waist height.

We went into this transition with 25+ years of soil-building experience. We didn’t mess around with small pots; we went straight for the biggest volumes we could find. We filled them with living soil. We treated them with the same “soil-first” philosophy we’ve always taught. We honestly thought it would be a simple “copy and paste” of our field success into a smaller footprint.

We were wrong.

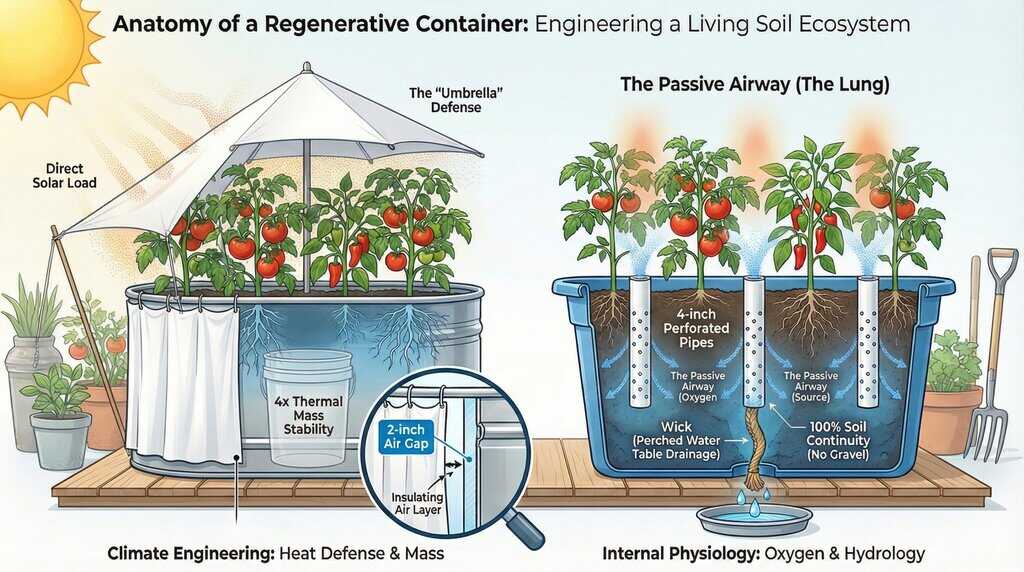

The Invisible Enemies: Inside a standard pot, the “Swamp” drowns roots while the “Dead Core” suffocates them.

The Diagnosis

Why Our Pots Were Failing

When we started analyzing our own failures, we realized we weren’t dealing with bad luck. We were dealing with hidden variables. In a raised bed, the earth forgives your mistakes. In a pot, there is no buffer.

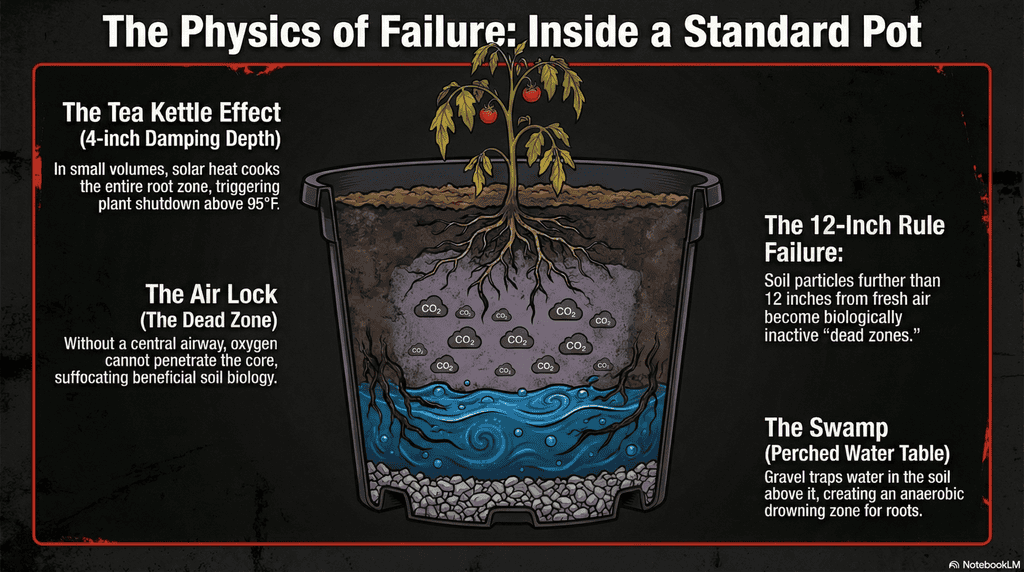

We discovered that standard containers fail because they create three invisible problems:

- The Heat Trap: Small pots heat up faster than roots can handle, triggering a biological shutdown.

The Swamp: The “gravel for drainage” myth actually creates a layer of stagnant, anaerobic water at the bottom of the pot.

The Air Lock: Without side-vents, the center of a large pot becomes an oxygen-starved dead zone.

We realized that to fix the biology, we first had to fix the physics. Here is the 5-step process we developed to turn our containers from “death traps” into thriving ecosystems.

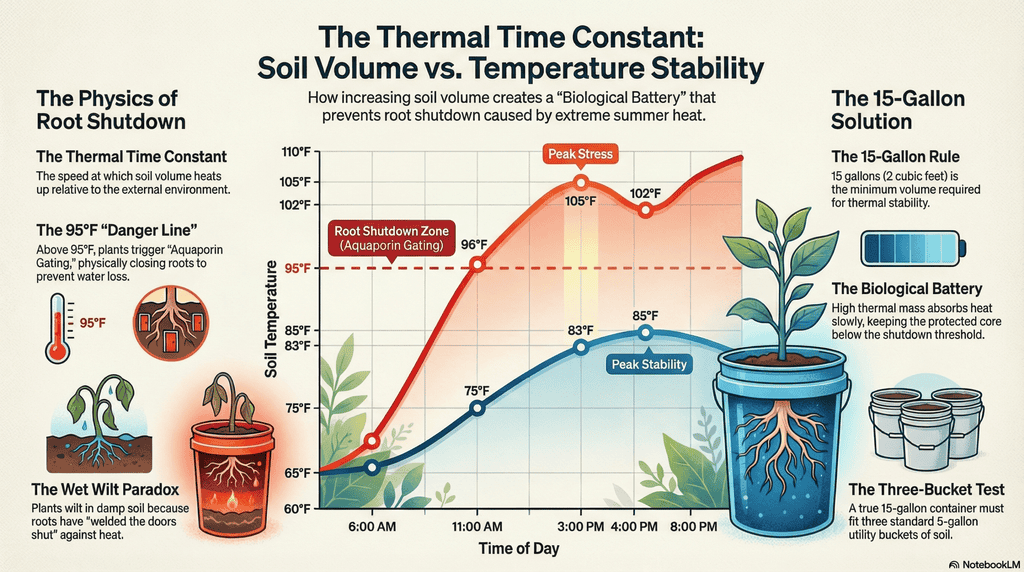

The Tea Kettle vs. The Battery: Small pots spike into the “Root Shutdown Zone” (>95°F) by noon, while large volumes maintain a stable core.

Step 1: The Biological Battery

Volume is Stability

In our raised beds, we never worried about the soil overheating. The sheer mass of the earth acted as a stabilizer. But in 5-gallon buckets, our peppers would wilt every afternoon, even when wet.

We learned that this is called the “Thermal Time Constant.”

A small volume of soil heats up rapidly—often in less than 2 hours. When the sun hits a small pot, the root zone spikes above 95°F. At that temperature, plants flip a survival switch called “Aquaporin Gating.” They physically close their roots to stop losing water. In regenerative container gardening, volume acts as a thermal battery.

This explained the “Wet Wilt Paradox” we kept seeing: The plant was sitting in mud, but the roots had welded the doors shut to survive the heat.

The 15-Gallon Rule

We found a clear stability line at 15 Gallons. Anything smaller than 15 gallons acts like a tea kettle; it heats up too fast for the biology to survive. A 15-gallon or larger (roughly 2 cubic feet) volume creates a “Biological Battery” that absorbs heat slowly during the day and releases it at night, keeping the root zone below 95°F.

- Why 15 Gallons? The sun’s heat wave travels about 4 inches into the soil each day (known as the Damping Depth—the point where the solar energy runs out of steam).

In a 5-gallon bucket, that heat wave consumes the whole pot. It behaves like a small tea kettle—it boils quickly.

In a 15-gallon pot, you have enough volume to absorb the heat while keeping a cool, protected core for the roots.

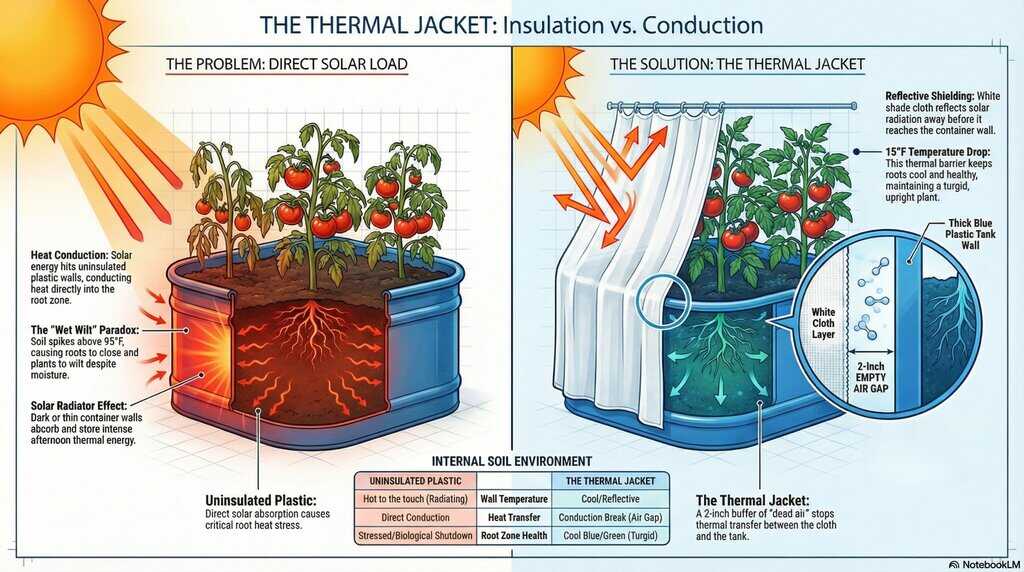

The Conduction Break: A simple air gap prevents the container wall from becoming a radiator, dropping root zone temperatures by 15°F.

Step 2: The Thermal Jacket

The Air Gap

Even with big pots, we noticed the sides facing the afternoon sun were hot to the touch. Inside, the roots against that wall were cooking.

We realized that any color plastic or galvanized metal acts like a solar radiator. We needed a shield.

The Solution:

Insulation, Not Just Shade

We put up shade cloth on the west side of the beds to shade the plants and soil, and that helped, but even with big pots, we noticed the sides facing the afternoon sun were hot to the touch. Inside, the roots against that wall were cooking.

The breakthrough was creating an “Air Gap.” A core principle of regenerative container gardening is protecting the root zone with a thermal jacket.

We started attaching white shade cloth to the outer rim of our troughs, letting it hang down loosely like a curtain. This creates a 2-inch buffer of dead air between the cloth and the plastic wall.

Why it works: The cloth reflects the radiation, and the air gap stops the conduction. It works exactly like a double-paned window—air is a terrible conductor of heat, so it acts as a shield.

This simple “Jacket” dropped our soil temperatures by 15°F, keeping those root channels open all day long. Combined with shading the plants and soil from above, this made all the difference.

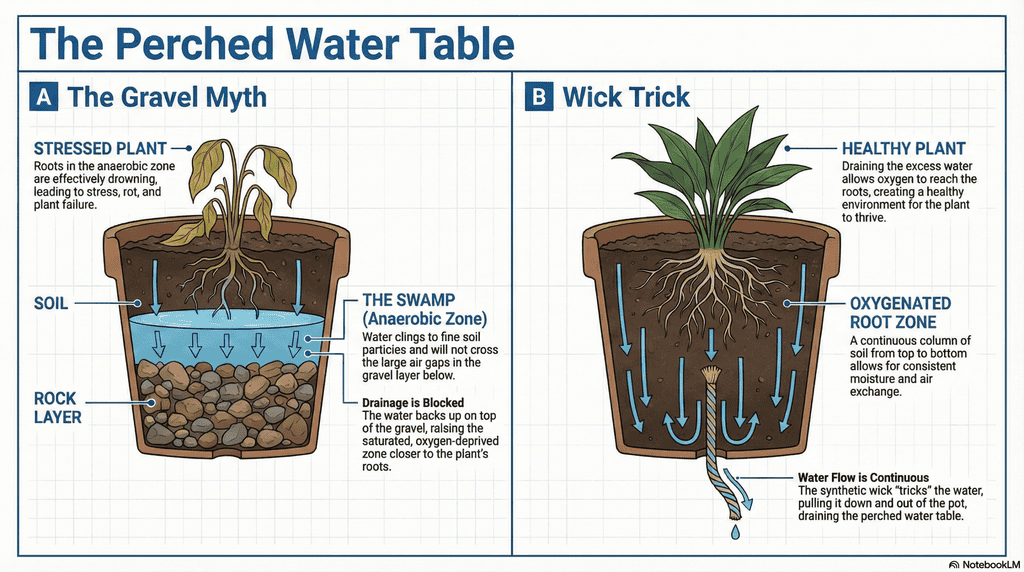

The Gravel Myth: Adding rocks actually raises the water table (Left). A soil wick restores drainage by tricking the water into flowing down (Right).

Step 3: The “Anti-Gravel” Protocol

Hydrology

This was the hardest habit for us to break. For 20+ years, we heard the same universal advice: put gravel or pot shards in the bottom of the container “for drainage.”

It turns out, that was drowning our plants.

Researching how soil physics works – how water moves through soil – teaches us about the “Perched Water Table.” Water does not like to move from a fine material (soil) to a coarse material (gravel). Instead of draining, it “perches” right on top of the rocks, creating a layer of anaerobic sludge. By adding gravel, we were actually raising the water table closer to the roots.

The Solution:

The Synthetic Wick

We stopped using gravel entirely. Standard drainage fails here. Regenerative container gardening uses a wicking system to manage hydrology. We now fill the pot with soil from top to bottom. To handle excess water, we installed a “Wick.”

- The Method: We use a long screwdriver to punch a vertical tunnel up through the central drainage hole into the soil. Then, we insert a 6-inch piece of synthetic rope into that tunnel.

The Physics: This “tricks” the water into thinking the soil column is deeper. The wick physically pulls the perched water out by gravity, sucking fresh oxygen down into the roots in the process.

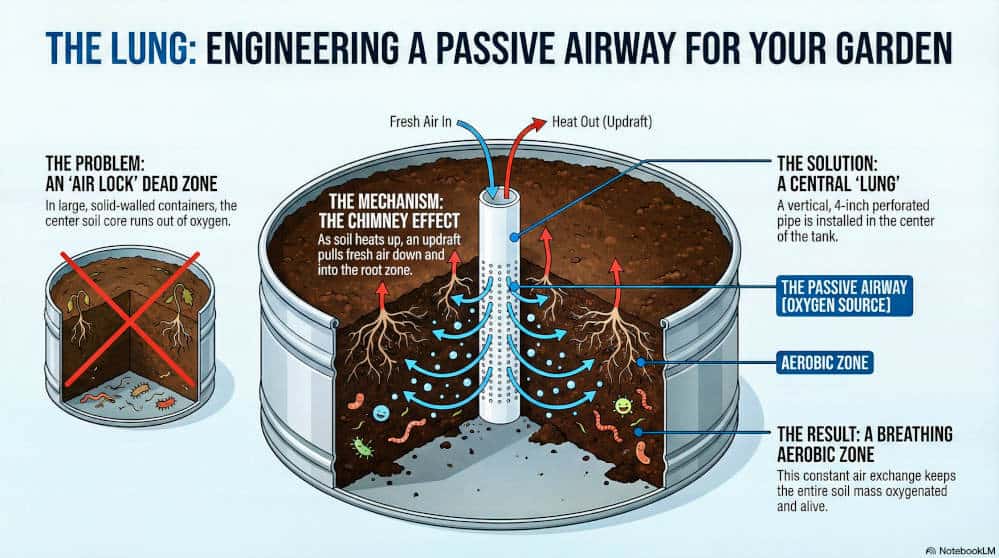

The Lung: In large containers, the center becomes a “Dead Zone.” This vertical airway uses the chimney effect to pull fresh oxygen down into the core, fueling beneficial microbes.

Step 4: The “Lung”

Aeration

When we moved to large stock tanks (over 2 feet wide), we hit a new problem. The plants in the middle weren’t thriving.

After once again diving into the world of soil physics – this time how air moves through the soil – we realized that while the edges of the pot could breathe, the center was a “Dead Zone.” Oxygen couldn’t penetrate that deep into the moist soil. We needed a way to let the center breathe.

The 12-Inch Rule

We adopted a strict engineering constraint: No soil particle should be more than 12 inches from fresh air.

To achieve this in big tanks, we installed a “Lung.” We placed a 4-inch perforated drain pipe vertically in the center of the tank. This creates a “Chimney Effect.” As the soil warms up, it pulls fresh oxygen down into the core and vents CO2 out the top. It turned our “Dead Zone” into the most biologically active part of the garden.

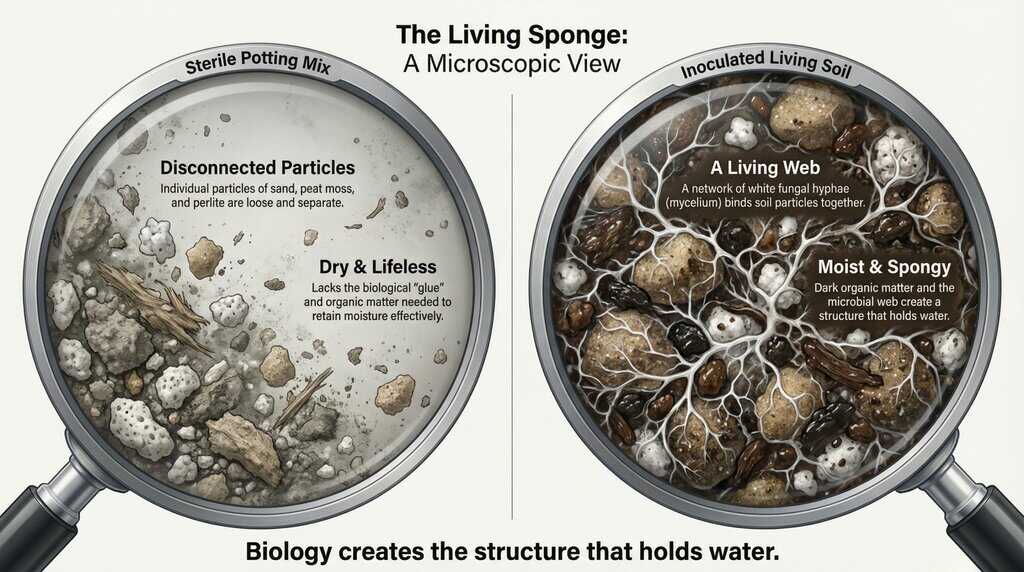

Structure holds water. The fungal web (mycelium) glues soil particles together, turning sterile dust (Left) into a moisture-retaining sponge (Right).

Step 5: The “Living Sponge”

Inoculation

Finally, we had to address the soil itself. Organic, bagged potting mix provides great structure, but it is biologically sterile. It’s a ghost town. In our raised beds, the worms and fungi showed up on their own. In a pot, we are the sole provider. If we don’t bring the life, it never arrives.

We use a “Slow vs. Fast” approach depending on how much time we have.

Option A: The Slow Way (The “Pre-Biotic” Smoothie) Best if you have 1 week before planting.

This is the standard approach, but it requires two specific ingredients: Worm Castings and Molasses/Milk.

You need both because they play different roles. Castings are essentially pure microbial life—packets of dormant bacteria and fungi waiting to wake up. The microbes in the castings are hungry; the sugar feeds the bacteria, and the milk enzymes feed the fungi.

- Inoculate: Mix high-quality compost or worm castings into your potting mix (10-15% by volume). This introduces the workforce.

Feed: Water the mix with a solution of unsulfured molasses and milk (1 tbsp each per gallon). This is the meal for the microbes.

Wait: Let the pot “cook” for 5-7 days. The microbes eat and go to work.

After 5 days of feasting, that dormant “workforce” explodes in population, gluing the sterile soil particles together into a moisture-holding sponge.

Option B: The Fast Way (The “Lightning Bolt”) Best if you need to plant in 48 hours.

We use a technique from the JADAM organic farming system (a streamlined cousin of Korean Natural Farming). JADAM translates to “People who resemble nature,” and its core philosophy is simple: Don’t buy generic microbes from a bottle; breed the indigenous microbes that already thrive in your climate.

The specific tool we use is called JMS (JADAM Microbial Solution). Instead of relying on sugar, JMS uses boiled potatoes as the food source. This creates a powerful, starch-based “breeding ground” that mimics the natural soil environment. By introducing a handful of local leaf mold to this starch water, you can explode a tiny population of native bacteria and fungi into the billions in just 24–72 hours.

The “Lightning Bolt” Recipe Brew this in a separate 5-gallon utility bucket to create a concentrate, then apply it to your larger pots.

1. The Brew (In a 5-Gallon Bucket):

- Water: 4 gallons of rainwater (or dechlorinated tap water).

Food: Boil 3 medium potatoes until soft. Mash them completely and mix them into the water. (This is the starch energy).

Bridge: Add 1 tablespoon of Sea Salt. (This provides minerals for cell structure).

Spark: Go to a healthy forest or under an old tree and grab a handful of “Leaf Mold” (the dark, decaying leaves and soil). Put this in a mesh paint strainer bag and massage it into the water.

Urban Alternative: If you don’t have access to a forest, use 1 cup of high-quality Worm Castings (fresh is best, but bagged works) or a handful of soil from a healthy, established compost pile.

Wait: Cover the bucket loosely. Wait 24 to 72 hours until you see a thick ring of foam on top.

2. The Application (For a 20-Gallon Container):

Do not use it straight. This is a powerful concentrate.

- Dilute: Mix 1 part solution to 10 parts water.

Drench: For a standard 15-20 gallon pot, mix 2 quarts of your brew into a 5-gallon watering can, fill the rest with water, and soak the soil until it drips out the bottom.

You have just added billions of indigenous microbes to your soil in one afternoon.