Italian Balsamic vinegar is pretty amazing, as even the “everyday” variety is highly tasty. Surprisingly, the traditional balsamic vinegar isn’t “true” vinegar in the classic sense of a fermented product that is removed from the fermentation after a specific period of time such as apple cider, wine or rice vinegar. Balsamic vinegar remains in the fermentation vessels for the entire time it is aging. It has been made in the Modena and Reggio Emilia regions since the Middle Ages, being mentioned as an established and highly regarded product in documents from 1046.

Traditional balsamic vinegar is produced by reducing pressed Trebbiano and Lambrusco grapes over low heat until the desired syrupy consistency is reached, called mosto cotto in Italian. This syrup, called a “must” is then aged for a minimum of 12 years in a series of seven barrels of successively smaller sizes. The barrels or casks are made of different woods such as chestnut, acacia, cherry, oak, mulberry, ash, and in the past, juniper. The results of this aging is a thick liquid that is a rich, glossy deep brown with complex flavors and aromas from the grapes and different woods that they’ve absorbed over time. The typical time for aging is 12, 18, 25, 50 and up to 100 years in those assorted wooden casks. No sampling is allowed until the aging is finished, and then a unique method of production is put into motion. A small amount of finished balsamic vinegar is drawn from the smallest and oldest cask, with each cask being topped off from the next largest and youngest cask. This happens once a year and is called “in perpetuum”. This is one of the reasons that certified traditionally produced balsamic vinegar can cost upwards of $150 – $400 for a 100ml bottle!

While we were at the Slow Food Terra Madre event in Turino, Italy last October, we were fortunate enough to be invited to sample several traditional balsamic vinegars produced in the Modena region, and certified as traditionally made. It seems that being tall, from Arizona and wearing my Australian Akubra hat gave us an open invitation with many of the food vendors that were eager to talk about the American West and share their culture!

This is what we were greeted with when he motioned us over to sample his treasures! There were some empty jam jars in front, followed by an apple and pear vinegar, made very similarly to how traditional balsamic vinegar is made, but not aged nearly as long – only 3 – 5 years. Very light, intensely fruity and delicious. We never knew that these kinds of vinegar existed.

Next he started sampling the aged balsamic vinegars. The 12 year bottle was the first one, much like what we are used to seeing in the United States in consistency, but darker and much more aromatic as he poured the small sample out onto our spoons. Even at almost arms length, we could immediately smell the complex aromas of wood cask aged balsamic. Our mouths were watering before ever tasting the first sample!

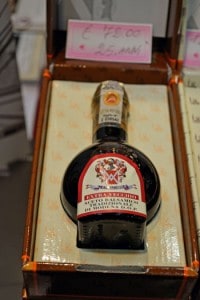

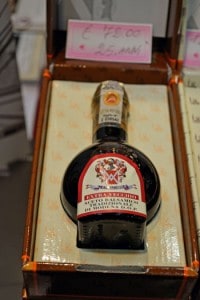

This is what the presentation or shipping box looks like for the 18 year old balsamic. You’ll notice the price – 47 Euros, which translates to about $63.00 in late 2013. That sounds expensive until you look online at what DOP certified balsamic vinegar produced in Modena sells for in the US. We didn’t taste this one, as there wasn’t an open bottle.

Next up was the 25 year old variety. Noticeably thicker in consistency, almost syrup-like. It moved slower out of the bottle and clung to the walls for longer. The aroma was much more complex and intense. The flavors really popped on the tongue with 4 or 5 flavors readily identified, then others showing up that surprised us. The flavors lasted for a long time, showing us how a tiny bit could be used for a powerful intrigue in dressings or sauces.

The presentation box for the 25 year balsamic, with pricing. 75 Euros is $100. It takes some dedication and patience to take a quarter of a century for a $100 bottle of vinegar!

We were then treated to a 50 year old balsamic vinegar. This was much thicker than the others, the gentleman had to shake the bottle a bit to get a few drops onto our spoons. It was different in that it didn’t have as much of an immediate aroma, but really lit off some fireworks of flavors in our mouths! As soon as it warmed up on our tongues, our sinuses were filled with multiple scents that continued to surprise us, coming from what was originally grape juice! The flavors didn’t just linger, they dominated our palates for a couple of minutes – to the point where we couldn’t smell anything other than this vinegar. After a couple of minutes lost in wonder at the craftsmanship and experience that created such a wonder, we took some swigs of water to prepare us for the Holy Grail of aged balsamic vinegars.

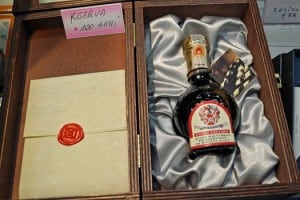

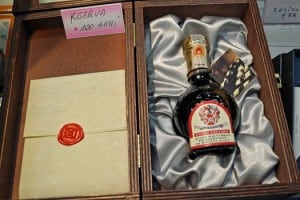

100 years of aging for this balsamic vinegar. He showed it to us, and I was very impressed that he would share such an expensive and precious delicacy with a complete stranger. I had read about these ancient balsamics, but had not expected to come across one or be invited to taste it. These highly aged balsamics are so valued that there are families that pass a bottle like this down from one generation to another.

All through this process, there were a number of people visiting his booth and a number of people were curious to see what we were sampling, but no one else joined us during the tasting. The proprietor explained in his limited English what we were tasting and the ages of the different samples. One of the impressive things that we experienced was the continuation of the flavors from the youngest to the oldest. There was a clear connection between all of them, with each successive taste getting stronger, more complex and more intriguing. It was like walking into a hall with a few doors, opening one to see hundreds more doors, then opening another to see thousands. That was what each taste was like!

The presentation box for the 100 year old balsamic is hand made of wood, with a satin lining to cushion the bottle. There was no price tag, but when we asked were told that it was “around 450 Euros” or $605 in 2013 dollars. It has been made this way since 1850 by the Malpighi family in Modena. They are truly connected with the land and the craft of making artisan balsamic vinegar.

It was an education and an honor to be invited to sample such flavors and aromas that take time and dedication to produce. It was another reminder of why food is truly important, why the quality matters and why care and dedication to craftsmanship remains a valuable part of our food pathways even in today’s ever-connected and busy world.

The Land Connection Foundation

The Land Connection Foundation