By all accounts, the FDA is a miserable failure for food safety.

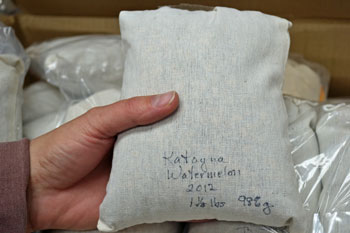

Many of us remember the national food safety nightmare – a listeria outbreak in cantaloupes from around Rocky Ford, CO – in the summer of 2011. All in all, there were 147 illnesses and 33 deaths, making this incident the most deadly outbreak of food-borne illness in our country since 1924. The farms owners declared bankruptcy later that fall. All of this occurred because of jerry-rigged potato cleaning equipment had been adapted to wash melons in conditions that heavily favored bacterial growth. There were no anti-microbial solutions – such as chlorine – used to kill the bacteria, only water.

As bad as this sounds, it is only the tip of the iceberg. The real tragedy, or crime, depending on how you view it is that not once in its 20-year history had the farm been inspected by the the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), tasked with the oversight of the safety of our food supply. A third-party inspection company was used by the farm, and accepted by the FDA as certifying the safety of the equipment and processes used in its handling systems. In fact, the company had one of its auditors at the farm at the time the first people were being sickened, and gave the processing facility a “superior” rating of 96 percent after a four hour visit.

This, sadly, is not an isolated major food safety incident. There are about 48 million cases of food poisoning each year, according to the Center for Disease Control. These result in more than 3,000 deaths. Affected foods include fresh vegetables and fruits, eggs, meat and cheeses – just about everything we eat! The rate of outbreaks and food recalls has been steadily rising since 2007. In a nutshell, our national food safety record sucks.

Why have these outbreaks increased in numbers and severity? What can be done about it? Let’s address the first question, then we will look at the second one. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has found that the FDA is riddled with shortcomings, both in the administration and regulation areas. The process it uses for product recalls is ineffective and confusing, it has waffled with the blatent overuse of antibiotics in animal feeding operations, and lacks the manpower to perform the scientific studies required to do its basic job of food and drug safety. When enforcement is attempted it only occurs about half the time and is half-hearted, with fines rarely imposed. It also accepts third-party inspections, which often have serious conflict-of-interest issues alongside questions of the quality of inspections, as shown by the cantaloupe fiasco. Another example is the Iowa based salmonella based recall of over 550 million eggs that led to the first (and only) inspection performed by the FDA, followed by a warning letter threatening “regulatory action”. A month later the company was allowed to resume selling eggs, with no corrective action being confirmed or other inspections performed. Yet another example was the salmonella outbreak in peanut butter in 2007. A plant was missed after an “intensive round of inspections” that was the cause of a second, more deadly salmonella outbreak. When that plant was finally inspected, it was found to have mold on the walls and slime covering the processing equipment.

One of the main reasons for the increased number of outbreaks is the amount of control the food industry has over the FDA. When an industry has enough political power, it uses that power to determine what the FDA will do in response to an issue. Unfortunately, that response is all too often to “do nothing” unless there are enough deaths to attract enough public attention to the issue. In addition to political pull, there is a “revolving door” policy where top industry people go to work at the FDA, sometimes while still drawing a paycheck from their “former” employers. Conflict of interest, anyone? One of the prime examples of this is Michael Taylor, a Monsanto attorney who prepared research on the constitutionality of states determining labeling laws for Monsanto’s bovine growth hormone rBGH. Then, once he had become the FDA’s deputy commissioner for policy, he wrote the guidelines for rBGH labeling policy for the FDA. Not surprisingly, they were in agreement with the research memo he worked on while at Monsanto. This is not an isolated case, either. There are many former and current employees of Federal regulatory agencies who are or were industry executives and vice versa.

Now to address the question of what can be done? Surprisingly, there are several possible movements afoot that might have a positive impact on the state of food safety. The Food Safety Modernization Act of 2011, a very controversial plan that was opposed by many smaller producers and supported by larger ones, may have some keys to this puzzle. It has been delayed with budget issues and has not gone into effect, but grants the FDA the power to prevent repeat offender from continuing to sell their product by revoking their registration. Another proposal by a Connecticut congresswoman would sever the ties of the food industry to inspection agencies. Third-party inspections can be effective if the inspector is not bing paid directly by the company they are inspecting. Some inspection companies have board members who are executives in client companies they monitor. Again, what conflict of interest?

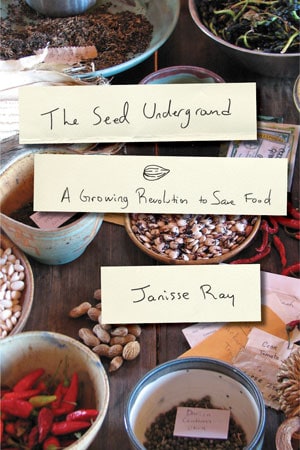

These are all well and good, but can the average person trust them to be effective? Will they measurably improve the quality of the safety of our food? That remains to be seen. In the meantime you can do what has been proven to be extremely effective so many times before. If you are concerned with the safety of your food, do something about it. Take a personal interest and responsibility for what you eat. This means doing some reading and research, asking questions and listening to the answers. You will establish your own “approved list” of food suppliers that you trust and those to stay away from. This will take some work, but probably much less than you think and for a shorter time period than you would initially expect. Once you establish a safe list, you won’t have to research each and every food item you buy, just the new ones that you aren’t familiar with.

Not surprisingly, you will quickly find that the majority of food producers you come to trust are the ones you can get to know. They will be local or regional, with small to medium sized operations. They will answer your questions and your phone calls, not minding that you need some answers. They will offer farm or facility tours, which you should accept. There are already several organizations that help with finding just these sort of companies. We’ve written about several of these, one is FarmPlate, another is Horsepower and yet another is Local Harvest. All of these are online tools to help you do what I just described, find quality and trustworthy sources of good, clean and fair food.

By taking responsibility for your food, you ensure that what you eat is to your standards. You also take that decision process out of the hands and control of a corporation and put it firmly in your grasp. You might be surprised at how the quality and safety of your food improves with much less cost than you expected.