There are a growing number of conversations and discussions taking place around the country, in person and online, about a highly important emerging question – how are we going to feed ourselves with a growing population, diminishing resources and a challenging climate?

We see news reports of crop devastation from droughts, floods and other weather related impacts around the world. There was a world-wide food shortage in 2008, causing a sharp spike in wheat prices that started a series of governmental overthrows in the Middle East. Clearly, food is important in a way that many have not thought about here in the United States. We didn’t experience much in the way of price spikes in 2008, but if we look, there is clear evidence that we are experiencing our own price increases; they are just in a different manner.

The prices for food, when compared to a couple of years ago, have risen significantly, even here in America. Our food system is complex, with major food companies and distributors absorbing the brunt of price increases and passing them along in increments, instead of all at once, so that we are not as aware of the increases in food prices. With a severe drought across most of the country in 2012, and winter moisture levels significantly below normal for this year (2013), more crop failures are predicted along with higher prices.

It is natural that this conversation is beginning to happen. In venues ranging from upscale coffee shops to rural diners to governmental meetings, more and more people are asking, “How are we going to feed ourselves?” The conversation more often than not becomes some form of commercial vs. small scale agriculture, with both sides speaking passionately about the benefits of their systems and judiciously pointing out the shortcomings and detriments of the other systems. It becomes an either/or argument and is a great example of false dichotomy.

We are not against large-scale farms, as there are a number of great examples of how size does not automatically mean a dependence on petro-chemical inputs, using fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides in an attempt to change a natural process into an industrialized, mechanical one to be controlled.

There is a need for a food production system of many sizes and for many reasons. We need diversity in size and scale, as it gives resiliency to our food system as a whole.

There is also an increasingly urgent need to re-examine our food distribution system, as there is an estimated 30 – 40% of food waste that happens before the food even reaches our homes. Utilizing this wasted food would go a long way toward easing hunger here in the United States.

There is also an increasingly urgent need to re-examine our food distribution system, as there is an estimated 30 – 40% of food waste that happens before the food even reaches our homes. Utilizing this wasted food would go a long way toward easing hunger here in the United States.

During the course of these conversations a logical disconnect often occurs. The commercial scale folks talk in solid, proven, real world terms and numbers. They should, as this is what they know. They talk about how only industrial farming can feed the world, as it will require their technology, equipment and inputs to grow twice as much food. These are terms that they are familiar with. When the alternative of small scale, local and sustainable agriculture is put forth, they begin to talk in relative and theoretical terms, partly out of ignorance as they are not experienced or familiar with this different approach to agriculture. Sometimes it will be as a dismissal of the effectiveness of sustainable agriculture.

Here is where the disconnect happens: when advocates of local and sustainable agriculture talk, they also tend to talk in theoretical and abstract terms, not in the proven, real world results based terms that the industrial ag folks use. This skews the entire conversation!

Some of this is understandable, as the definition of “local and sustainable agriculture” is completely opposite on the spectrum of commercial and industrial. It is hard to speak about total food production or capacity from the local and sustainable model as it is from the commercial one, for the simple reason that there is more documenting and reporting of figures in large scale agriculture, with almost none in the local one.

This doesn’t mean that alternative agriculture has nothing to contribute. Far from it. Sustainable agriculture, on any scale, is a highly important contributor to the conversation, and our future. There is a school of thought that states, “We will ultimately wind up in a sustainable economic and agricultural model, either by choice or by force.” I’m going to ignore the economic portion of the statement for this article, as it is beyond the scope of our focus.

The thought goes on to show how we don’t have a choice on becoming sustainable in agriculture, as we simply cannot continue our current path of mining our soils of nutrients and using petroleum as a replacement. The petroleum is used for transportation, to power the mining equipment extracting the minerals used to replace those lost in the soil, and for herbicides, pesticides and petro-chemical based fertilizers. Both the nutrients and petroleum are finite, we all know this. What we don’t know is precisely when these resources will run out. They are becoming more expensive each year, looking past short-term fluctuations.

We can make the choices to move our food production into a model where we aren’t strip-mining the earth of its nutrients to grow our food, or we will wind up with no more petroleum to replace these critical nutrients, and our food production on any scale comes to a halt, with devastating consequences. We at Terroir Seeds are working on the choice solution – rather than force – helping to create a better, healthier, more productive, diversified, decentralized and independent food production system that everyone has access to and can participate in, no matter where they live.

We can make the choices to move our food production into a model where we aren’t strip-mining the earth of its nutrients to grow our food, or we will wind up with no more petroleum to replace these critical nutrients, and our food production on any scale comes to a halt, with devastating consequences. We at Terroir Seeds are working on the choice solution – rather than force – helping to create a better, healthier, more productive, diversified, decentralized and independent food production system that everyone has access to and can participate in, no matter where they live.

During the conversation on feeding ourselves, several examples of sustainable agriculture that are currently being practiced are usually brought up, such as Cuba. When Cuba suffered the oil embargoes and trade restrictions, many citizens died from the catastrophic decrease in daily calories as a result of very limited food production on the island in relation to the size of the population. Everyone lost around 30 pounds as they struggled to find ways to grow all of their own food with most people having little to no gardening experience and a loss of machines to work the land. Eventually they did succeed, and today Cuba is an example of small, local and sustainable agriculture feeding the population.

This example is pooh-poohed by the industrial ag proponents, “Of course Cuba can grow their own food, they are a tropical island, they can grow anything. It’s not like that here or in the rest of the world.” They ignore the difficult history and work that it took for Cubans to be able to grow their own food.

What if there was another example; one of an industrialized, well-populated country that is larger than the USA, grows about half of its total food production in home gardens in a difficult and short-season climate, with no machines or animals to help? Would that example suffice to show that local, small-scale, sustainable agriculture can be a proven, viable alternative to the industrial agriculture model?

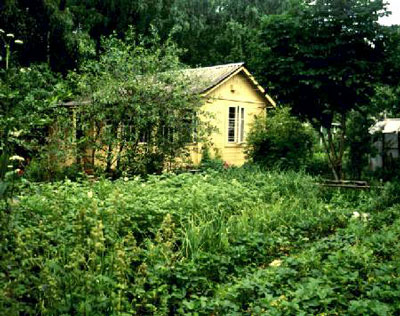

That example is Russia, and the model is called dacha gardening. It has provided food for the people of Russia for over 1,000 years, starting as mainly subsistence or survival gardening and evolving into an independent, self-provisioning model between the Bolshevik Revolution and World War II and continues into today.

That example is Russia, and the model is called dacha gardening. It has provided food for the people of Russia for over 1,000 years, starting as mainly subsistence or survival gardening and evolving into an independent, self-provisioning model between the Bolshevik Revolution and World War II and continues into today.

The term dacha, dating back to at least the eleventh century, has had many meanings; from “a landed estate” to the rural residences of Russian cultural and political elite. Since the 1940s, the term “dacha” has been used more widely in Russia to define a garden plot of an urban citizen. This is when the urban populations began to rapidly expand their garden plots to provide food for themselves, their families and neighbors.

Dacha gardening accounts for about 3% of the arable land used in agriculture, but grows an astounding 50% by value of the food eaten by Russians. According to official government statistics in 2000, over 35 million families (approximately 105 million people or 71% of the population) were engaged in dacha gardening. These gardens provide 92% of Russia’s potatoes, 77% of its vegetables, 87% of the berries and fruit, 59% of its meat and 49% of the milk produced nationally. There are several studies that indicate that these figures may be underestimated, as they don’t take into account the self-provisioning efforts of wild harvesting or foraging of wild-growing plants, berries, nuts and mushrooms, as well as fishing and hunting that contributes to the local food economy.

Clearly, there is something to be acknowledged and studied here! Of note to us Americans, dacha gardening or self-provisioning gardening was the foundational reason that the Russian people did not experience a famine in the early 1990s after the USSR collapsed, and the state sponsored, heavily subsidized, industrial commercial agriculture collapsed along with it. This drew the attention of researchers seeking to find an explanation. Several attempts to explain it away as only a survival strategy have failed, especially when the extensive historical context is examined. Dacha gardening is much more than merely survival, and has always been.

This was not reported outside of Russia, as it wasn’t considered newsworthy. What is truly newsworthy today is that we as a nation aren’t in as favorable of a position if there were a similar catastrophic occurrence in our food distribution, power grid or dollar value. We are all too dependent on outside sources for our food, with most Americans tied to the grocery store and its 3 day supply of food being constantly trucked in.

Russian household agriculture – dacha gardening – is likely the most extensive system of successful food production of any industrialized nation. This shows that highly decentralized, small-scale food production is not only possible, but practical on a national scale and in a geographically large and diverse country with a challenging climate for growing. Most of the USA has far more than the 110 days average growing season that Russia has.

Russian household agriculture – dacha gardening – is likely the most extensive system of successful food production of any industrialized nation. This shows that highly decentralized, small-scale food production is not only possible, but practical on a national scale and in a geographically large and diverse country with a challenging climate for growing. Most of the USA has far more than the 110 days average growing season that Russia has.

Today’s dacha gardening closely resembles the peasant gardening production of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This shows a continuation of methods and techniques that have proven effective in a small scale garden that works as well today as 200 years ago. The Russians do not use machines – tillers or tractors – or animals on their garden plots, cultivating them in much the same way as the peasants did in the 18th Century.

Dacha gardening is not and never has been simply a survival strategy – a response to poverty, famine, adverse weather or social unrest. Recent studies have shown that Russian food gardening is a highly diverse, sustainable and culturally rich method of food production. This was initially recognized almost a century ago and has been confirmed more recently.

If examined through a strictly economic lens, dacha gardening makes no sense at all. There is much more labor as a dollar value invested than is harvested, but that isn’t the point of this type of system at all. The function of dacha gardens goes well beyond their economic significance, because they serve as an important means of active leisure as well as a way to reconnect with the land. Traditional economic calculations fail to realize the true value and benefits of a dacha garden. Clearly, a wider viewpoint is needed to realize all of the benefits! Time spent in the garden is seen as relaxation, education, entertainment and exercise – all in one. Food production is a very valuable bonus.

Despite their significant contribution to the national food economy, the majority of dachas mostly function outside of the cash economy, as most dacha gardeners prefer to first share their surplus with relatives and friends after saving enough to feed them through the winter, and only then look at selling what remains. A few will sell the remainder at local markets, and move into a small market production model for extra cash.

The Russian mindset relating to the sharing of surplus food is important to examine, as it is one of the keys that ensure the success of the dacha gardening model. In dacha gardening, people will share their excess food out of a sense of abundance or plenty. It is a very positive and powerful motivator which creates an upward, positive spiral of sharing among the community.

For example, a neighbor helps you to build a fence on your property. Instead of paying them money for their help, you give them 50 pounds of apples from your tree. These apples have little monetary value for you, as you have all of the apples you can use for the year stored up, canned, made into apple butter and jams. You are sharing your abundance. The neighbor is overwhelmed, as this is a considerable gift for a few hours of work, so he feels compelled to share some of his gardens abundance with you, for the same reason. He shares from his abundance. This process continues around the neighborhood until there is a solid network of people actively sharing food with one another. This system creates a resilient food network that is not only local and sustainable, but has many other positive benefits as well.

For example, a neighbor helps you to build a fence on your property. Instead of paying them money for their help, you give them 50 pounds of apples from your tree. These apples have little monetary value for you, as you have all of the apples you can use for the year stored up, canned, made into apple butter and jams. You are sharing your abundance. The neighbor is overwhelmed, as this is a considerable gift for a few hours of work, so he feels compelled to share some of his gardens abundance with you, for the same reason. He shares from his abundance. This process continues around the neighborhood until there is a solid network of people actively sharing food with one another. This system creates a resilient food network that is not only local and sustainable, but has many other positive benefits as well.

There are no feelings of “owing” from one person to another. When someone gives food to another, it is not “charity” or putting them under an obligation to repay. It is an exchange of excess freely given with no thought of repayment or obligation.

Economic profit is only one of the potential benefits of this type of food production. Other economic components are increased food security with a robust, decentralized and local food supply and distribution. Agricultural sustainability, conservation of bio-diversity and the preservation of heirloom varieties are some of the environmental contributions of dacha gardening. Socially, dacha gardens help create community and a connection with the land and nature.

In addressing the question of “How are we going to feed ourselves?”, we have a lot to consider in looking at the effective, proven and ongoing examples that Russian dacha gardening has to offer us. A closer study of the methods and especially the mindsets will help all of us become more resilient and self-sustaining in our food systems right here at home.