Papalo – Heat Loving Cilantro Alternative

Papalo is a fabulous, but still relatively unknown, ancient Mexican herb you should be growing. A heat-loving alternative to cilantro, its flavors are both bolder and more complex. It has been described by some as somewhere between arugula, cilantro and rue; others say it tastes like a mixture of nasturtium flowers, lime, and cilantro. Younger leaves are milder flavored, gaining pungency and complexity as they mature.

Papalo (PAH-pa-low) is known by many names; Quilquiña, Yerba Porosa, Killi, Papaloquelite and broadleaf in English. It is a member of the informal quelites (key-LEE-tays), the semi-wild greens rich in vitamins and nutrients that grow among the fields in central and South America. These green edible plants grow without having to plant them. They sprout with the first rains or field irrigation, often providing a second or third harvest, costing no additional work but giving food and nutrition.

Other quelites include lamb’s quarters, amaranth, quinoa, purslane, epazote and Mache or corn salad.

Papalo pre-dates the introduction of cilantro to Mexico by several thousand years, which is a very interesting story all by itself. South America is thought to be the ancestral home of papalo.

Cilantro is also known as Chinese parsley and was brought to Mexico in the 1500s by Chinese workers in the Spanish silver mines of southern Mexico and South America. Spain had a huge trade industry with China, exchanging silver from America for china, porcelain and various drugs – opium and hashish among them. They also imported many Chinese workers for the silver mines, as European diseases had decimated the native population which had no immunity. The Chinese workers brought along foods, herbs and spices which were familiar to them, so cilantro came to the Americas.

Papalo is sometimes called “summer cilantro” due to its heat-loving character and its delay in bolting and setting seed until late summer or early fall.

The name Papalo originates with the Nahuatl word for butterfly, and Papaloquelite is said to mean butterfly leaf. The flowers provide nectar to feeding butterflies, while also attracting bees and other pollinators to the garden with their pollen.

Part of the aroma and flavor is seen above with the oil glands which look like spots on the underside of the leaves. Those glands produce a fragrance which repels insects from eating its leaves.

There are two different leaf shapes grown – a broadleaf and a more narrow leaf, often called poreleaf. We have found the broadleaf variety to be more palatable, quite a bit more pungent than cilantro but quite tasty. When beginning to use papalo, start with 1/4 to 1/3 as much as the normal amount of cilantro. The flavor is much stronger and lasts longer, so a little goes a long way until you’ve gotten used to it. We grow and offer only the broadleaf variety.

When we hear about people complaining of papalo tasting of soap, detergent or having a rank or funky odor, usually they have encountered the poreleaf or narrow leafed variety. It is quite a bit more pungent than the broadleaf type, so usually comes as quite a shock to our palates.

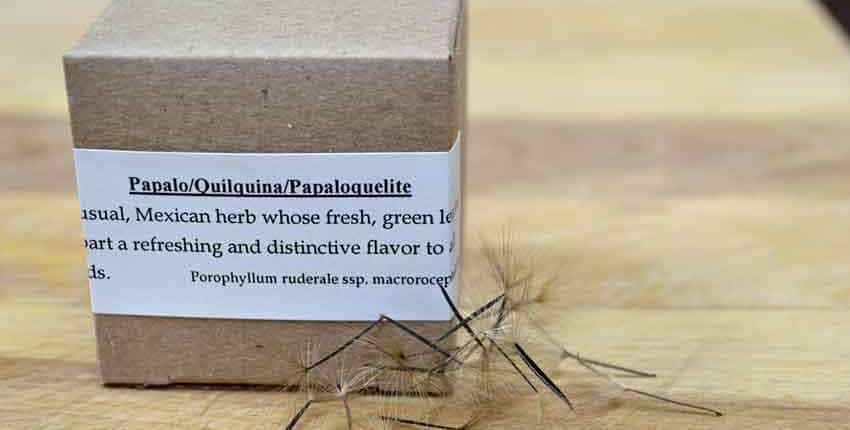

Papalo seeds look much like dandelion seeds, with the stalk and “umbrella” to help carry them on the wind to their new home. Having the umbrella attached is very important to good seed germination, which we will show you in just a bit.

The harvested seed comes from our grower in a big clear plastic trash bag, as it just isn’t possible to harvest and clean the seeds without breaking the umbrellas off. The seeds are almost weightless, so a big bagful that you can hide behind weighs less than a pound.

Cindy has a handful of seed heads, showing how they clump together after maturing. As the seed matures, the sheath or covering that protects the young seeds peels back, exposing these clusters to the wind, which will carry them away as they dry.

A closer look at the clump of seeds. We haven’t found a better way to separate them without damaging them, so we usually pack them much like this – by the ever so gentle pinch! There are probably 30+ seeds in this photo.

Papalo is often described as having “very low and variable” germination. This is true if the seed is packed in a standard seed packet, which breaks off the umbrella from the stem. From experimenting, we have found germination will drop to around 10% if the seed is broken, but will be as high as 90% or better if the seed is intact.

This photo of papalo in our germination tray shows the proof. Using seed germination paper to keep the seed damp, there was 100% germination in less than 72 hours. In fact, the seedlings hit the lid of the germination chamber, trying to get to the light.

A close-up shows how the stem emerges from the bottom of the stalk, immediately turning vertical in growth, searching for light.

Seen in Cindy’s hand it is easier to identify the parts of the seed and where the seedling emerges from, as well as how tall they can grow in a short time.

We have developed this simple but highly effective packing box from our germination experiments. It keeps the seeds intact for planting as well as protecting them from being broken during shipping.

Young seedlings don’t have the oil glands developed yet, so they are milder in flavor and aroma than when they begin to mature. This planting is a bit thick, but it is sometimes difficult to separate the seeds without damage. In this case, just plant them thick and don’t worry about it. If desired, you can clip the unwanted or unneeded seedlings to thin them. Make sure not to pull them out, as this really disturbs the roots of the adjacent plants and seriously disrupts their growth.

Even in a very harsh spring with sustained high temperatures and punishing winds, the young papalo grows strongly. The weather effects can be seen in the drying of the leaf margins, as well as the scruffy and dry leaf appearance. The holes are not from a bug chewing on the leaves, but from the oil vaporizing from the porous oil glands. The lighter colored spots on the leaves are additional oil glands.

A fully mature papalo leaf in good growing conditions looks like this – a moderately deep, rich green with oil glands distributed across each leaf. The leaves have a medium thickness to them with a fairly substantial feel. They don’t feel delicate like some vegetable leaves, but aren’t thick and succulent either.

Touching them will release some of the aromatic oils, so you should be able to immediately experience their singularly unique aroma, even from an arm’s length away. This is the same with organically grown or home-grown cilantro – the aroma will be much more pronounced.

The seed heads start out looking much like marigold flower heads. After flowering, they will set seed and begin the cycle anew. When harvesting seeds to save, make sure to clip the seed head after it has fully matured and begun to dry but before it is completely dry. Otherwise, you will go out to the garden to collect seeds to find it has all blown away!

In October 1999, when Alice Waters, renowned chef of Chez Panisse in Berkeley, California, first tasted one variety of papaloquelite, she was ecstatic and demanded to know why she had never experienced it before. She purchased every seed packet available from the Underwood Gardens booth at the Taste of the Midwest Festival, an annual event sponsored by the American Institute of Wine and Food.

When we met Alice at Slow Food Terra Madre in Turin, Italy, in 2012, we mentioned this past connection. She immediately remembered the event, and her eyes lit up when we discussed the aromatic flavors and how she introduced them to her restaurant patrons.

It’s always used raw and added at the last minute, giving its signature, unique piquant flavor to dishes. It’s used in fish dishes, salsas and guacamole. There is a memorable guacamole that uses cucumbers and papalo for added depth of flavor that we can’t get enough of. We also really like it in scrambled eggs, fresh salsas, and finely diced in a strongly flavored salad of spinach, arugula, mustard greens, and kale. Devilled eggs take on an entirely new dimension with a couple of leaves finely diced and mixed into the filling. People always try to guess the mystery seasoning and always mistake it for something else.

In restaurants in the state of Puebla in Mexico, it’s common to find a sprig of papalo in a glass jar of water on the table, next to the salt, pepper and salsas — ready to be added raw to soups, tacos, tortas or beans. The diners will take off a leaf or two and tear it up finely before sprinkling it over their meal.

Papalo is very easy to grow and has a history stretching back thousands of years, so give it a try in your herb garden this season!

I received my Papalo seeds in a carefully shipped small cardboard box. Wow, there are alot of seeds! I was able to share with several friends and still place three seeds each into 12 Coir pellets. Within 3 days they began germinating under grow lights and on a warming mat. I’m excited to try these!!!

Don, glad to hear!