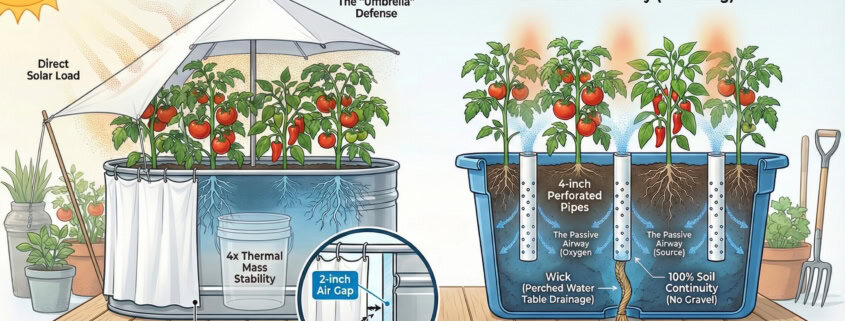

Why do most pots fail in August? It’s not water; it’s physics. Discover the 5 engineering principles of regenerative container gardening—from “Thermal Jackets” to “Wicking Beds”—and learn how to build a living soil system that thrives in the heat.

Discover the importance of soil health for thriving gardens. Shift your focus and partner with nature for better results.

Learn how to work with your soil’s natural processes – protecting it, feeding its living workforce, minimizing disturbance, increasing plant diversity, and watering thoughtfully – to create the foundation for truly flavorful harvests and a more resilient garden with less work.

Discover the power of cover crops for easy soil improvement in your garden. Enhance soil health, suppress weeds, and attract beneficial insects with these natural helpers.

Cover Crops Boost Fertility While Beating Weeds

Historically, our soils were developed through the interaction of diverse plant and biology growth but much of this has been lost through large scale commercial agriculture becoming increasingly dependent on chemicals to feed the plants, instead of the soil and its organisms. This “trickle-down” effect has also affected home gardeners and small scale growers, and now we struggle to find ways to bring that plant diversity back to the garden.

Planting a multi-species cover crop in your garden will greatly stimulate the soil life and biology while suppressing weeds, interrupting disease cycles and even supply nutrients for next season’s crops.

We spend a significant amount of time teaching straightforward ways home gardeners can improve their soil, so we are often asked: “How can I manage pest and disease issues in my garden?” The simplest answer is: “Improve your soil.” Immediately followed by: “Plant a cover crop.”

The next question we hear is usually: “How will that help my pest and disease issues?”

Let’s take a closer look, and remember that a diverse cover crop mix can accomplish several of these at once.

We’ll start with a few of our customers’ gardens and let them tell you about their experiences in their own words! Then, we’ll explain how and why planting a cover crop in your garden this season will boost your soil’s fertility.

Crimson Clover

Tomatoes with Crimson Clover cover crop. A perfect illustration of the “no bare soil” concept.

“Experimented in one of my six raised beds (4’W x 16’L) and was very happy with virtually no weeds. Plan to use this as a between plantings cover crop going forward!!”

– Skipper

“I needed a ground cover that would improve my really bad soil and offer the disappearing bees and pollinators a refreshment stand. As usual, Terroir filled the bill. I planted these seeds in several different locations and they sprouted and grew in every one of them – from crushed granite mixed with sandy soil to soil that had been covered for YEARS by heavy green plastic. Full sun, partial shade – it made no difference. They thrived.

And two days ago they started to bloom AND I saw three honey bees land on them. “

– Karen

Garden Cover Up Mix

“Germination was excellent. I have a beautiful cover crop that the bees are totally enjoying. This mix has been the easiest cover crop I have ever planted, no fuss, very little upkeep, just add a little moisture. It’s so magnificent I spend 5-10 minutes every day just enjoying it.”

– Linda

“I’ve grown vegetables in my 4 4’x12′ raised beds for over 25 year, renewing the soil annually with a layer of compost; yields had become just OK. Two autumns ago I planted the Cover Up Mix, turned it into the soil in spring, covered the beds with the usual compost; happily report last year’s yields were up appreciably. The garden was positively lush (an unusual state in our high desert environment with 2017’s prolonged high summer heat). So I planted your cover crop mix again last fall and am looking forward to this year’s results. Definitely recommend!”

– Kerry

“First time I’ve used a cover crop; planted 6 weeks ago in 1/2 of my garden because the other half was still producing. Easy to plant, grew quickly with great coverage. The best part is that everywhere the cover crop was planted there are NO WEEDS! Morning glory has been my biggest problem and I have none where I planted the cover crop. Seeing the comparison between the two halves has made me a believer… already re-ordered enough for the whole garden for next year, and plan on using it in my flower beds, too. Highly recommend!”

– Pamela

Soil Builder Mix

“Great germination, fast early growth and very thick. Really looking forward to better soil.”

– Victoria

“I love this! It is growing so healthy and lush. I love the great variety of plants in it. It will get turned in as a green manure day after tomorrow and I am so looking forward to reaping the benefits!”

– Donna

How and Why Cover Crops Work

Suppress Weeds

The best way to suppress weeds is with a highly competitive crop that quickly forms a canopy and shades weeds out. Summer annual cover crops like buckwheat and crimson clover form tight, dense canopies and will often outgrow many weeds. A diverse mixture of cover crops like our Garden Cover Up Mix – which includes both buckwheat and crimson clover – is much more weed-competitive than a single species.

Reduce Weeds in Next Year’s Garden

Planted in late summer or early fall as part of our Garden Cover Up mix, cereal rye is one of the best weed-suppressing tools if your next crop in that bed will be a legume like beans, chickpeas, lentils, peas, or soybeans as it aggressively ties up nitrogen – leaving little for weeds to use.

The legumes don’t mind, as they just fix their own nitrogen.

If your next crop is nitrogen demanding like corn or green leafy vegetables, a fall legume like hairy vetch can be used to both produce nitrogen and suppress weeds. Vetch does make nitrogen, but when it is cut or frost-killed the nitrogen is a protein and must decompose before it is available to either crop or weeds.

Both rye and hairy vetch form a thick mulch when cut that helps suppress small-seeded weeds like Palmer amaranth – better known as pigweed – by starving them of sunlight after germination so they run out of energy. Both rye and vetch produce biochemical compounds that stunt weed growth, called allelopathy.

Fix Nitrogen

This is best accomplished with a diverse mix dominated by legumes like our Garden Cover Up Mix. Remember, mixtures are capable of fixing much more nitrogen in a more stable and plant-useable form than single-species cover crops alone.

Build Soil Organic Matter

As gardeners, this should be our very first priority.

As we have learned more about how soil organic matter is formed, we have come to realize the most important contributor to soil organic matter happens in the root zone through what is known as root exudates – biologically active compounds deposited into the soil through the roots – and not simply the aboveground plant growth as previously thought.

Therefore, the best and fastest way to dramatically improve your soil health and fertility is through significantly increasing root growth of a diversity of species and plant families, along with as much aboveground biomass as possible.

Diversity of plant families makes for a more nutritious diet for the soil organisms that build organic matter in the soil, as some species have root exudates high in sugar, others high in protein, others high in lipids, while others are high in minerals; when combined, it makes a more complex and balanced diet than a single cover crop can provide. In general, since the production of root exudates depend on the level of photosynthesis, the more biomass a plant produces, the higher the root exudates and the faster you build soil organic matter.

To Really Build Soil Organic Matter

Inoculate your first planting with our mycorrhizal fungi – MycoGrow. Mycorrhizal fungi form mutually beneficial relationships with plant roots, extending their reach and monitoring nearby soil nutrients, feeding needed nutrients that are otherwise out of reach of the plant roots.

The soil proteins – called glomalin – produced by the mycorrhizal hyphae is the most persistent form of organic matter known and does wonders for the soil.

Now It’s Your Turn

Hopefully, you have a much better understanding of why and how cover crops can make a big positive difference in your garden, no matter if you have a traditional row garden, raised beds, or large containers. If you have soil, cover crops will improve it!

We’ve watched the skepticism on people’s faces when we talk about the multiple benefits of using cover crops in their garden, but then when they try them, the skeptical looks turn to astonishment when they describe how much better their gardens performed.

Help Us Help You

Did this help you understand cover crops better? Do you know a gardening friend who could use this information in their garden?

Please share this with your friends – either with the buttons below or on your social network of choice.

Soil Elixir Jump-Starts Your Garden’s Soil

One of the most anticipated times of year for gardeners is Spring, with the attendant planting season. Everything is new and fresh, a chance to start over and improve on last year’s garden. A big subject for gardeners is what to do with the soil to prepare it for planting. If you have been reading our articles over the past several years, you know we advocate building the health and vitality of the soil in a natural, biologically safe manner. Soil becomes healthier, more productive, and disease, weed, and pest resistant. It results in an upward spiral where the garden gets better year after year.

Here is a unique recipe for a spring garden elixir that is easy to mix, completely non-toxic, and hugely beneficial for jump-starting your garden’s soil and getting it ready for planting. It comes courtesy of Crop Services International, which has over 35 years of experience helping growers accomplish their goals. They provide a Non-Toxic/Biological/Sustainable approach to growing food, from a full-scale commercial farm to the home gardener. We have read “The Non-Toxic Farming Handbook,” which they wrote to educate ourselves on improving our knowledge and approach.

This recipe is based on a 20′ x 50′ garden or 1000 sq. ft. Adjust for your garden size.

Before You Start

This recipe and applications assume an average garden soil that is basically good but could use some help.

It works in fertile soils by subtracting the lime or gypsum application, adding compost before spraying the elixir.

It helps very poor soils, but won’t give as much effect.

Preparing your garden beds for the elixir will require a couple of things.

First, evenly spread a 50 lb bag of high calcium lime (for acidic soils) or gypsum (for alkaline soils) across your beds. Your local garden center should have this. If using lime, it should be high calcium lime with as low magnesium as possible. 5% or less is great, up to 10% is acceptable, but nothing over 10%. The higher magnesium percentage releases excess nitrogen into your soil, greatly decreasing its fertility. It also overloads both the chemical and biological processes of your soil. Do not buy Dolomite lime, as it has too much magnesium.

Then, follow with 100 lbs of rich, aged compost, spread evenly across your beds, about 2 full-sized wheelbarrows. This can be purchased or from your own compost pile. Again, the best is made by you, and it is easy – “Compost – Nourishing Your Garden Soil” has all the details.

After doing both of these, make and apply the elixir.

Notes on Ingredients

- When purchasing the fish fertilizer, if you can find one with kelp or seaweed, even better. If you want the absolute best fish emulsion possible, brew your own! Read our “Best Homemade Fish Emulsion” for the recipe and instructions.

- Blackstrap molasses is best for its increased mineral content. Unsulphured is preferred but not absolutely necessary. One of the best sources of inexpensive molasses is a feed store that supplies horses, which can be bought by the gallon for much less than at a supermarket.

- Do not buy diet cola, as the Aspartame/NutriSweet used as the sweetener acts as a chelating agent, meaning it ties up the minerals and nutrients in the soil, making them unavailable to the plants. (It also does the same thing in your body!) The cola has Phosphorus to add to the mix along with sugars.

- The beer adds B vitamins – no, not vitamin Beer!

- The Borax powder adds Boron, one of the most important elements in the biochemical sequence of plant growth.

- Cranberry juice is full of vitamins and minerals, acts as an antibacterial agent, and has an acidic pH. Depending on how the juice is processed, it can also contain significant amino acids.

This recipe is based on a 20′ x 50′ garden or 1000 sq. ft. Adjust for your garden size.

- 20-24 oz liquid fish fertilizer Home-made is best

- 1/2 cup molasses Black strap has more nutrients

- 16 oz bottle of cola – NOT DIET!

- 24 oz beer 2 - 12 oz cans, any beer works

- 1/2 cup Borax powder

- 1 qt cranberry juice – make sure to get 100% cranberry juice, not a dilution

- Mix well with a stirrer and thin with enough water to enable mixture to be sprayed with a tank type or hose-end sprayer.

Apply the mix evenly over lime or gypsum and compost base with sprayer. If needed, go back over with second application to use up all of the batch, just make sure to apply evenly.

Broad-fork or lightly rototill garden soil. If using a rototiller, don’t go more than 2 inches deep at the maximum. Most of the biological growth happens at the 2-3 inch mark and the soil is turned over an inch or so beyond what the tines reach. Tilling deeper only destroys microbial life in the soil, setting you back in your efforts to create and build biologically active soil.

It must be noted that the sprayer cannot have been used to spray any chemical treatments like herbicides, pesticides, etc. as this will put those chemicals onto your soil, killing the microbial life in the soil and feeding the chemicals to the plants, where you wind up eating them!

Seed Planting Elixir

Once you have applied the elixir and broad-forked or lightly tilled the soil, prepare your garden planning and seedlings. We have another planting elixir to use just after planting the seeds and transplanting the seedlings into the garden that we’ll share with you: In a gallon milk jug, mix 1/2 cup of fish emulsion, 1 tsp sugar (preferably raw or brown), and 1/2 cup of cola. Fill the jug with water and shake well. Apply the mixture over the seeds and transplants. Each gallon will treat approximately a 50-foot row.

This is a great start towards sustainable, biological agriculture in your own garden. Remember, though, it is just a start, a good step in the right direction. To continue to make progress in knowledge and soil health, you need to find out where you are starting from. Do more reading, ask questions, and get a complete soil analysis, not just the widely offered NPK and pH soil tests. Spend the money to find out exactly where your garden soil is, and then you can make sound decisions on where you want and need to go. Then you won’t be guessing and shooting in the dark, trying to do what is right but not really knowing if you are making positive progress.

A Universe in Your Hand

In a handful of soil from your garden, you hold potentially billions of different living organisms hard at work making your soil a better place for your plants to live. Most of these team players are microscopic – too small to see with the eye, but a few are large enough to observe. Bacteria, fungi, mycorrhizae, protozoa and possibly algae are on the microscopic side while earthworms, pillbugs, arthropods and some nematodes are big enough to see in your hand.

We pay lots of attention to improving soil, for good reason. Healthy, fertile soil grows stronger, healthier, more productive plants while reducing insect and disease damages. You see and taste the difference in richer, brighter colors and sweeter or more flavorful vegetables and fruits.

Most attention focuses on the structure and chemistry of the soil – is the soil made up of sand, loam, clay or some mixture? The chemistry shows what nutrients are present and in what amounts. This is the common approach but leaves out one of the biggest components of soil improvement – the biological community.

It’s easy to overlook them because they can’t easily be measured – like determining soil structure or reading a soil analysis for nutrient deficiency.

There’s a saying among soil consultants that,”You must build a house for the biology.” That means that soil structure and chemistry must be aligned before the beneficial organisms can fully go to work. It also recognizes the critical but often overlooked role they play. Beneficial soil organisms release tied up nutrients in the soil and move them into the reach of plant roots, improve soil structure and increase nutrient retention, among many other things.

Now that you understand a bit more about them, let’s introduce you to your team!

The Big Boys

Starting with the larger, more visible players-

Earthworms – An acre of good garden soil can have between 2 and 3 million of these black gold producing workers, constantly processing organic matter into readily available nutrients your plants absolutely love.

That means each square foot of good soil in your garden can have up to 45 – 70 earthworms. You won’t be able to see all of them, as they can range a few feet deep.

Arthropods – are ants, mites, and springtails who voracious shred decomposing plant leaves, stems, and mulch. They do the heavy lifting, getting the plant organic matter into bite-sized pieces for the smaller team members.

Pillbugs– are land-based crustaceans, distant cousins to lobsters, crabs, and shrimp. They are scavengers, mainly feeding on moist, decaying plant materials – very useful in shredding dead plant matter so it can be fully decomposed.

If you see these guys in your handful of soil or in your garden, you are doing several things right. They won’t stick around in dead soil with little or no organic matter, or in soils that are heavily contaminated with pesticides.

The Little Guys

Now, on to the smaller and less visible players that are no less important –

Fungi – More common in woodland soils or in areas where woodchips have been laid down. They can appear as mushrooms with stems and caps – especially after a rain – but are more often seen as a whitish growth on moist and decomposing parts of the woody material. They send out hyphae or long, thin strands to decompose organic materials, transport nutrients, and improve soil structure while stabilizing it.

Protozoa – Single-celled animals that are always busily feeding on bacteria, soluble organic matter, and sometimes fungi. As the feed, they release nitrogen that is used by plant roots and other players on the team.

Actinomycetes – (pronounced act-in-o-my-seetees), are special beneficial bacteria that are responsible for the rich, earthy smell of freshly turned soil. Their specialty is digesting the high carbon cellulose in wood and the chitin of shed pillbug shells and insect bodies.

Beneficial bacteria – These microorganisms are more common in the nutrient-rich garden soils, forming associations with annual vegetables and grasses.

Beneficial nematodes – Not all nematodes are destructive, and these guys search out, infect, and kill targeted destructive insects. Different nematode species attack different pests.

Mycorrhizae – A very specialized fungi that bond with the tiny, hair-like roots of plants in a mutually beneficial relationship. The fungi send out hyphae into the soil to bring back specific nutrients needed by the plant, in return for a sugar-based plant sap that feeds the mycorrhizae. In essence, they feed each other what they can’t get for themselves. Mycorrhizae can only survive on living plant roots, and about 95% of our garden plants depend on their fungi friends to thrive.

Help Your Team Out

Now that you’ve met the team working tirelessly for you in the garden, help them out with making sure they’ve got food, water, and shelter – which compost provides almost everything for them!

When you hear someone talk about “beneficial soil organisms“, you will know exactly what they mean!

Soil Builder vs Garden Cover Up Mix – which is best for your garden?

Both of our cover crop mixes give you multiple benefits in the soil and above it. You can’t go wrong with either one. The Garden Cover Up mix is a general use cover crop, while the Soil Builder mix is more specific toward improving the overall condition of your soil.

Cover crops improve soil in a number of ways. They protect against erosion while increasing organic matter and catch nutrients before they can leach out of the soil. Legumes add nitrogen to the soil. Their roots help unlock nutrients, converting them to more available forms. Cover crops provide habitat or food source for important soil organisms, break up compacted soil layers, help dry out wet soils and maintain soil moisture in arid climates.

It’s always a good idea to maintain year-round soil cover whenever possible, and cover crops are the best way.

Let’s look at how cover crops work overall, then we’ll see the differences of each mix.

Most cover crop mixes are legumes and grains or grasses. Each one has a different benefit to the soil. Legumes include alfalfa, clover, peas, beans, lentils, soybeans and peanuts. Well-known grains are wheat, rye, barley and oats which are used as grasses for animal forage.

Legumes

Legumes help reduce or prevent erosion, produce biomass, suppress weeds and add organic matter to the soil. They also attract beneficial insects, but are most well-known for fixing nitrogen from the air into the soil in a plant-friendly form. They are generally lower in carbon and higher in nitrogen than grasses, so they break down faster releasing their nutrients sooner. Weed control may not last as long as an equivalent amount of grass residue. Legumes do not increase soil organic matter as much as grains or grasses. Their ground cover makes for good weed control, as well as benefiting other cover crops.

Grains or grasses

Grain or grass cover crops help retain nutrients–especially nitrogen–left over from a previous crop, reduce or prevent erosion and suppress weeds. They produce large amounts of mulch residue and add organic matter above and below the soil, reducing erosion and suppressing weeds. They are higher in carbon than legumes, breaking down slower resulting in longer-lasting mulch residue. This releases the nutrients over a longer time, complementing the faster-acting release of the legumes.

This pretty well describes what our Garden Cover Up mix does, as it is made up of 70% legumes and 30% grasses.

Our Soil Builder mix takes this approach a couple of steps further in the soil improvement direction with the addition of several varieties known for their benefits to the soil structure, micro-organisms or overall fertility.

For example, the mung bean is a legume used for nitrogen fixation and improving the mycorrhizal populations, which increase the amount of nutrients available to each plant through its roots.

Sunflowers are renowned for their prolific root systems and ability to soak up residual nutrients out of reach for other commonly used covers or crops. The bright colors attract pollinators and beneficials such as bees, damsel bugs, lacewings, hoverflies, minute pirate bugs, and non-stinging parasitic wasps.

Safflower has an exceptionally deep taproot reaching down 8-10 feet, breaking up hard pans, encouraging water and air movement into the soil and scavenging nutrients from depths unreachable to most crops. It does all of this while being resistant to all root lesion nematodes. Gardeners growing safflower usually see low pest pressure and an increase in beneficials such as spiders, ladybugs and lacewings.

Now you see why you can’t go wrong in choosing one of our cover crop mixes! Both greatly increase the health and fertility of the soil, along with above-ground improvements in a short time. Even if you only have a month, the Garden Cover Up mix will impress you for the next planting season.

For a general approach with soils that need a boost but are still producing well, the Garden Cover Up mix is the best choice. Our Soil Builder mix is for rejuvenating a dormant bed or giving some intensive care to a soil that has struggled lately. Both will give you a serious head start in establishing a new growing area, whether it is for trees, shrubs, flowers, herbs or vegetables.

Let one of our cover crops go to bat for you and see what happens when you play on Mother Nature’s team!

Can cover crops improve garden soil in one month?

Cover crops – also called green manures – have improved soil for thousands of years. 3,000 years ago Chinese agriculture began planting horsebeans and sesame for soil improvement. Much later the Greeks and Romans sowed special crops to increase soil fertility.

The past 60 – 80 years has seen an incredible amount of knowledge emerge from small farmers experimenting with planting different cover crops and learning from what resulted. This knowledge was built on a foundation of several hundred years of European trial and error.

We now have access to detailed information about how to use cover crops for the maximum benefits in our gardens, pastures and fields.

Our Garden Cover Up Mix was developed from research into the specific benefits we wanted to bring to the home garden soil, as well as what species supported each other.

This photo essay is a look at what one month – 4 weeks – of growth provides in an average raised bed.

After sowing we began watering with our drip system, but the monsoon rains provided a good amount of water over the month. This helped the plant growth along, so your results may be a week or two behind these photos.

Week One

At one week, the mix has almost all sprouted and shown vigorous growth. The oats and rye are shooting up, looking like grass while the buckwheat spreads its leaves and the clover hugs the soil. The peas were just beginning to show up, as they took a few days longer to absorb moisture and begin germinating.

We planted the different parts of the mix separately to get an idea of how they grew by themselves and with other species in support.

The rye and oats both shot up rapidly, germinating within 3 – 4 days and showing good soil coverage.

The crimson clover was also up fast, creating a fluffy green blanket over the soil with its tiny green leaves. Even with only an inch of growth it was easy to feel the temperature differences between the tops of the leaves and the soil temperature – it felt like 15°F difference!

The buckwheat was a couple of days slower coming up than the oats or rye. Once the sprouts appeared they immediately opened their leaves and really started growing.

Week Three

After three weeks the mix has almost completely covered the raised bed. The root system is about 3/4 of the top growth at this point, so the root density below the soil is almost as much as seen here. This is why cover crops are so beneficial to soil fertility.

A closer look shows how much shade the soil has and how thick the mix is growing. This out-competes most weeds above the soil while the roots choke out weeds below.

The young seedlings have just finished emitting auxins, a natural root hormone that inhibits other seeds from growing.

This mechanism gives the cover crops a head start over any other weeds for the next 2 – 3 weeks. When weed seeds can’t germinate, they will often rot as the soil fertility improves.

Week Four

The growth accelerated going into the fourth week, as these photos show. The white PVC stake is about 14 inches tall. Last week the growth was about 3 – 4 inches, but this week it shot up above the top of the stake.

Besides putting on a lot of height, the mix also completely filled in the raised bed. Weeds have no space to grow and we could only find one or two after searching for them.

The soil is much cooler than the surface of the leaves. It is also moister, but that could be due to the amount of recent rains and not the cover crop. The buckwheat is starting to bloom and is attracting bees as seen in the top photo detail.

The buckwheat is the tallest of the mix at about 21 inches tall. The mix is extremely full and thick up to about 16 inches, completely choking out any weeds. The root system is still about 3/4 of the height of the plants, so there is an amazing amount of roots below ground! This shows why planting cover crops does so much to improve the physical structure of the soil.

As the roots die and decay they add organic matter to the soil, open up moisture and air pathways where the roots grew and increase the carbon content – all at the same time!

Pretty good for a few minutes spent planting the seeds and a months’ worth of growth!

Both the rye and oats look like really lush grass. They completely cover the soil and top out at just over 15 inches at one month. We couldn’t find any weeds in this test plot.

Looking closer at the density of the rye planting, it is easy to see why weeds don’t stand a chance. There is no room for anything other than the rye with this dense seeding rate, which is the point.

Next Steps

If a killing frost happened tomorrow there is enough growth to create an excellent mulch while the root system will feed the soil and its microbial populations.

Our first frost is still several weeks off so the cover crops will keep growing both above and below the soil level. The flowers need watching to prevent setting seed and creating another crop next season. We will clip or mow the flower heads as they develop if there isn’t a frost soon enough.

If the rest of the mix can develop before mowing or a killing frost, it gives more nutrition and benefits to the garden bed.

Cover crops will increase the bio-available nutrition in your soil for next season, even if you use a well-aged compost. Both approaches have benefits but if used together support each other and create a better, more fertile soil sooner than if only one is used.

You don’t need a lot of time to grow a good cover crop and seriously improve your garden soil – a month will do! Even if you only have 2 – 3 weeks you will be better off with a shorter planting than none at all.

Go plant some cover crops. Your garden will reward you handsomely next season!

Cover Crops Q & A

Our cover crop mix has generated lots of questions on how to use it. This means we need to share more information with you. It is fantastic seeing so much interest about improving your soil and your garden!

I’ve taken the most frequent questions and condensed them into a Q&A format below.

“I want to order cover crop seed. I don’t know how much I need, how to prepare the garden before sowing the seeds and when to plant it.”

The Garden Cover Up mix page lists the coverage rates for each variety.

1 lb will seed 200 square feet, or a 10×20 garden bed or 2 5×10 beds. 8 oz will seed 100 square feet, or a 10×10 garden bed. This gives you a thick planting, boosting soil fertility and decreasing weed pressures.

Ideal planting times are early August through mid-September, depending on your growing season. Plant around mature garden vegetables or in spaces left from the removal of older plants.

Preparation is easy. Broadcast the seeds and rake them into the top half inch of moist soil, or cover with 1/2 inch of mulch or compost. Water equal to 1 inch of rainfall per week until seedlings become established.

The best time to plant is 6 – 8 weeks before your first frost date. If you don’t know your expected first frost date, use the First and Last Frost Dates tool from the National Garden Association.

Enter your ZIP code and find the weather station closest to you.

The first frost date is the intersection of the vertical 50% column and horizontal Fall 32°F line.

Count back 6 to 8 weeks to determine when you should sow the cover crop seed. By planting a few weeks early you’ll have bigger growth, but may need to clip the spent flowers to prevent re-seeding.

“Can/should cover crops be used in raised beds? Approx 3-4′ X 6-8′. Do they need to be turned in the spring? Do they go to seed and become intrusive?”

Cover crops are good for any sized garden larger than a container garden where it is easier to change the soil out. Your raised beds would benefit from our cover crop mix.

If you get a good freeze, the mix will “winterkill”, meaning they will die after a hard frost of around 24°F or so. Then the plant matter will fall down to become mulch for the soil, while the roots decompose. You can turn them under, but I don’t recommend it as tilling or turning disturbs the soil structure. You can plant right among the mulch in the spring.

The cover crops will set seed and scatter those seeds if you let them. Plant cover crops 6 – 8 weeks before the first frost so they get good growth and flower but usually don’t have the chance to set seed. If you see seed forming, just clip those seed heads off and throw them away.

This way the cover crop can’t be an unwanted guest next spring!

“I would like to start a cover crop on a small portion of my property and put in a garden next year. What do I have to do to prepare the soil to put in a cover crop. Also, when do I turn over the cover crop?”

You have a great thought in using the cover crops to help establish and improve the garden soil for next season.

This is the exact method used by organic farmers and growers to prepare fallow soil for a crop. Growers will plant cover crops in succession, or they allow the flowers to re-seed themselves.

Rake to loosen the top inch or so, broadcast the cover crop seed and rake again until just covered. Water the area equal to 1 inch of water per week until the seeds sprout and the plants establish themselves.

Let the plants flower and start setting seed, then clip the heads to prevent them from re-seeding. Allow the plant matter to die in the frost, creating its own mulch. The roots and topsoil mulch decompose over the winter, giving you with an excellent start to next gardening season!

“I am slowly working toward taking my area back from prairie dogs and building a garden plot on 4 acres that are usually dry and sandy. Do you have a general ground cover seed mix to assist in soil health and holding my sand back from flowing away during the monsoon season?

I keep chickens with portable netting so something edible for them would be good.”

Our Garden Cover Up Mix provides plenty of nutritious forage for your chickens. Plant a test plot close to where they are. Water the area equal to 1 inch of water per week until the seeds sprout and the plants establish themselves. Then you can trim some as fodder for the chickens as it grows and develops.

Our Backyard Chickens collection is another option. It has a variety of tasty edibles like sunflower, corn, Swiss chard, mustard and kale.

For erosion control, I would plant a straight (50/50) mix of buckwheat and cereal oats. Both are fast growing with good root systems that hold the soil in place. They provide good mulch after the plant dies off. You might test plant a strip about 3 – 5 feet deep crosswise to how the water flows during monsoon season. This acts as a catch strip, slowing the water down and reducing the amount of soil moved. It also creates a berm for future moisture retention. The roots create a “sink” for the water flow which diverts the water into the soil and away from flowing across it. This starts to build up the shallow soil and water reserves on your property.

I would not mow or kill this planting but allow it to re-seed and establish itself well. If the test works, you can replicate this downstream of where the water flows as many times as needed.

Once the initial berm starts to form, plant the Garden Cover Up mix up stream. This takes advantage of the extra moisture to reclaim and build some good soil!

This will only take 2 or 3 seasons to establish some excellent berms fully and then you can plant more.

“I have celiac disease and therefore cannot be around wheat, and am also sensitive to oats. Do you have any other recommendations?”

Buckwheat is not related to wheat at all, as it is in the Rhubarb family – if you can believe that! You should not have any reaction to buckwheat. You can avoid the oats by ordering the individual cover crop varieties. The Crimson clover and hairy vetch are strong nitrogen fixers, where the Buckwheat and Rye are fast growing ground covers.

You can make your own mix by ordering the smaller amounts of the individual cover crops, avoiding what you are sensitive to.

“After the cover crop dies or you kill it – should you till it into the ground?”

The cover crop mix will die after a couple of hard frosts. It becomes a mulch insulating and protecting the soil over the winter. During that time the roots decompose and increase the soil fertility. Depending on your climate over the winter the mulch should almost dissappear by next spring’s planting time.

I don’t recommend tilling a cover crop, it disturbs the soil you spent the winter improving. When planting, open a small space in the mulch. Then it continues covering and protecting the soil while smothering weeds.

If you do feel the need to till, raise the tines to only till the top 2 – 3 inches of soil and don’t disturb deeper layers. This will work the decomposed vegetative matter into the soil where it will be used quickly.

The process is to plant a fall cover crop, let it die and overwinter to improve the soil. Next spring, plant another after the garden crops are in and up. This covers the soil and shades out most weeds. Repeat this cycle yearly and the soil becomes incredibly fertile after a year or so.

In fertile soil weeds aren’t as much of a problem because they just don’t germinate as well. Fewer weeds leads to fewer insects, as many insects “partner” with specific weeds for habitat or to lay eggs on. Increased soil fertility means healthier plants which do not attract predatory insects.

“I planted clover one fall as a cover crop, and found that in spring it had formed such a dense mat of roots I had to use a pickax, and it never DID die back in winter! (Living in a warmer winter climate.)

I have clay in my soil and have been amending it for several years now. Wouldn’t tilling the soil deeply (about 12 inches) be beneficial for breaking it up and making it more accessible to my garden plants’ root systems? It’s really solid and unfriendly down there in the root zone!”

Thanks for your question! That’s why you need to kill the cover crops manually if the weather doesn’t freeze cold enough to kill them. Mowing or weed-whacking is the easiest way to do this. Otherwise, the plants don’t die, the roots don’t decompose and you struggle to plant your garden.

If you kill the cover crops from late October to mid-November, they will benefit the soil!

There are a couple of ways to open up the soil, especially with a clay component.

1 – You can deep till the soil. Realize you are destroying many micro-organisms as you are completely changing where they live. This is ok once or maybe twice when first establishing the garden, but is detrimental to the soil health if done often.

2 – Use a broadfork or other mechanical means to open up the soil without disturbing the layers. This is often done by hand, so will only work in a smaller garden. Because you won’t be able to drill down deep in a hard soil, this might need to be done a few times over a couple of seasons.

3 – Plant cover crops or aggressive root crops such as sunflower, wheat, sesame or Daikon radishes which drill down and open up the soil. This isn’t a one time, fix-all solution, but with replanting in spring and fall the cover crops can continue building and improving the soil.

Do you know about the magic of milk and molasses in improving your garden? Yes, plain old milk of any kind – whole, 2%, raw, dried, skim, or nonfat – is a miracle in the garden for plants, soil, and compost. Molasses only boosts the benefits! Let’s see how and why they work.

Milk as Soil Food

Using milk on your compost and in your garden will probably come as a surprise to most.

Upon closer inspection, however, it starts to make sense. The amino acids, proteins, enzymes, and natural sugars that make milk a food for humans and animals are the same ingredients in nurturing healthy communities of microbes, fungi, and beneficial bacteria in your compost and garden soil.

Raw milk is the best, as it hasn’t been exposed to heat that alters the components in milk that provide the perfect food for the soil and plants, but any milk will provide nutrition and benefits. Using milk on crops and soils is another ancient technique that has been lost to large-scale modern industrial agriculture.

Milk is a research-proven fungicide and soft-bodied insecticide – insects have no pancreas to digest the milk sugars. Dr. Wagner Bettiol, a Brazilian research scientist, found that milk was effective in the treatment of powdery mildew on zucchini. His research was subsequently replicated by New Zealand melon growers who tested it against the leading commercially available chemical fungicide and found that milk out-performed everything else. Surprisingly, they also found that the milk worked as a foliar fertilizer, producing larger and tastier melons than the control group.

David Wetzel, a Nebraska farmer, completed a 10 year study on applying milk at different ratios to his pastures, and recorded the results with the help of a team made up of the local Agricultural Extension agent Terry Gompert , a university soil specialist, a weed specialist and an insect researcher.

What they found was amazing- the grass production was drastically increased; the soil porosity or ability to absorb air and water doubled; microbe activity and populations increased; cows were healthier and produced more milk on treated pastures; the brix or sugar level in the pasture tripled, indicating more nutrients were stored in the grass than before. Grasshoppers abandoned the treated pastures- the sugars are poison to destructive soft-bodied insects as they do not have a pancreas to process the sugars.

This also explains why damaging insects leave healthy, high-brix-level plants alone, as they contain more sugars than stressed and sickly ones. Read Milk Works As Fertilizer for the full article.

Home Gardener Recipe

For the home gardener, the ratio can range from 100% milk to a mixture of 20% milk to 80% water, with no loss of benefits.

Use as a spray on the compost and garden soil before planting and as needed when insects appear. Spray directly on the insects and around the areas they inhabit. When combined with molasses, it becomes a highly beneficial soil drench.

A proven solution is 20% milk – 1 cup of milk to 4 cups of water, or 2 cups of milk to 8 cups of water for larger gardens. Whatever amount you need, the 20% ratio has been proven to give the most effective results with the least amount of milk.

David Wetzel’s experiments found that 3 gallons of milk per acre benefits pasture grasses most, so the costs are minuscule compared to the benefits!

Molasses Feeds Micro-Organisms

Molasses is a viscous by-product of the processing of sugar cane or sugar beets into sugar.

Sulfured molasses is made from young sugar cane. Sulfur dioxide, which acts as a preservative, is added during the sugar extraction process. Unsulfured molasses is made from mature sugar cane, which does not require such treatment.

There are three grades of molasses: mild or Barbados, also known as first molasses; dark or second molasses; and blackstrap. The third boiling of the sugar syrup makes blackstrap molasses. The majority of sucrose from the original juice has been crystallized and removed. The calorie content of blackstrap molasses is still mostly from the small remaining sugar content. However, unlike refined sugars, they contain trace amounts of vitamins and significant amounts of several minerals.

Blackstrap molasses is a source of calcium, magnesium, potassium, and iron; one tablespoon provides up to 20% of the USDA daily value of each nutrient. Not only do these nutrients do a body good, they are highly valuable in building up the soil!

Molasses is a very valuable addition to the compost pile, as well as to the garden itself. Unsulfured blackstrap is the preferred variety due to the mineral content, but any of the unsulfured ones will do fine. The benefits beyond the minerals are the natural sugar content that will feed the microorganisms in the compost or soil of the garden.

More Gardening Recipes

Use 1/4 to 1/2 cup of molasses to a gallon of water and spray onto the compost pile or garden, or add to the drip system for the garden. For soils that are poor, stressed, or need help, use 1 cup; for those that need a little “snack, “use 1/4 cup. The readily available sugar content will skyrocket the microbial activity.

Apply once or twice a month, but be careful not to overdo it – don’t train the microbes to expect you to feed them, only give them a boost when they need it!

Blackstrap molasses is also commonly used in horticulture as a flower blooming and fruiting enhancer, particularly in organic hydroponics. Use the before mentioned mixture in the drip system, or sprayed alongside the roots of fruiting vegetables as they start to flower to increase their flowering and fruiting.

Add 3 Tablespoons of molasses to the milk spray solution mentioned above and use to feed plants during the height of growing season. Hungry, high production plants such as tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, melons, and such will really benefit from the consistent feedings, giving you more production that is more flavorful.

Sweet Weed Control

A fringe benefit of spraying the milk and molasses mixture on the garden is biologically friendly weed population control. Many broadleaf weeds thrive on diets high in available nitrates and potassium diets, common with commercial fertilizers. Phosphorus is “tied up” or bound with calcium in the soil and needs biological activity to release it. The calcium in milk helps to compensate for what is unavailable in the soil, while the increased biological activity from both the milk and molasses releases unavailable phosphorus and creates soil conditions that are unfavorable to the germination of weed seeds.

Minimal Costs

The costs of applying the milk and molasses mixture are minimal, but when compared to any other fertilizer and insecticide regimen – even those that are organic in nature – milk and molasses have no comparison.

For instance, one acre has 43,560 square feet, and a gallon is 128 oz.

Doing the math, we find that 3 gallons per acre is 0.003 of an ounce per square foot!

Assuming a gallon of organic milk costs $8.00, that works out to 0.00055 dollars per square foot or 0.055 cents per square foot! Yes, that is right – when rounded up, it is six-tenths of a penny per square foot of garden.

So if you had a large garden – say 1,000 square feet – one application of the milk would cost a whopping $0.55 (55 cents), plus the expense of 2 – 3 tablespoons of molasses. What other biologically friendly soil fertility improvements would cost this amount?

Here’s the proof of the math:

1 acre = 43,560 square feet (ft²)

1 gallon = 128 ounces

128 oz/43,560 ft² = 0.002938 oz/ft²

3 gallons x $8 = $24

$24/43,560 ft² = $0.00055/ft² multiply this by 100 for cents = 0.055 cents/ft²

Who knew that something as simple as milk and molasses had such powerfully positive, far-reaching effects? Especially without any of the negative effects of petrochemical fertilizers?

We are sharing an article that we’ve written for magazine publication and has been in the October 2013 issue of Acres USA as well as the Fall 2013 edition of Small Farmer’s Journal. Compost is one of the foundational cornerstones of any successful garden, but has been over-thought and made much too complex by people wanting to make it “faster” or sell you some piece of equipment or machinery to make it “better”. It really is simple to make and doesn’t take any equipment, only needing time to accomplish. After all, who turns and works the compost in nature?

This is about our experiences and what we’ve learned from about 15 years of composting. Enjoy!

What We’ve Learned from Compost

Having been gardening for 15 years and composting for almost as long, we quickly realized that with our climate and native soils, improving the soil’s health and quality were one of the most important things we could do to help our garden. We are located in North-central Arizona, which is a semi-arid high grassland environment. Historically there would be 18 – 20 inches of moisture per year, but we have been lucky to see 10 – 12 inches in a good year over the past 20 years. There is almost always a south-westerly breeze which pulls moisture from any unprotected ground. The soils are really varied in structure with many different types in close proximity to each other. It is not uncommon to have a good productive soil with a caliche or high sandy soil within 20 – 50 feet. Our garden is a good sandy loam, with decomposed granite about 30 feet to the east and a heavy clay caliche soil 20 feet to the west.

Good, aged compost has helped us build the health and fertility of our soil and overcome many of the challenges we face in our garden. It improves the soil structure, brings the micro nutrients and biological life to the soil, along with earthworms and larger soil dwellers. Mulching the compost helps to retain needed moisture and brings the soil moisture level from about 2 inches down to the surface of the soil/mulch interface. We use a combination of straw and wood chips for our mulch.

There is much we have learned that we have applied to our approach in creating great compost, along with observations and education we have sought out along the way. We are happy to share some of our experiences and knowledge about compost.

We don’t turn our compost, partly from being busy and not wanting to invest in machinery or equipment, also partly from research, reading and talking with those who have learned how to create some incredibly rich, earthy compost that looks like highly fertile soil. Most compost tumblers are too small for our needs and a tractor or turning equipment is an expensive purchase for the occasional use.

Our compost piles will age for at least a year before being added to the garden. We have learned that the slow aging is more beneficial to the decomposition process as well as not losing nearly as much nitrogen to off-gassing as happens with the hot and fast methods. Another benefit is the decomposition is much more thorough, destroying weed seeds, pathogens and any unwanted chemicals much better in a slower composting setup. In our climate, we need to water our compost occasionally to keep it going. This is easy to gauge, as the rich earthy smell goes away when the moisture level drops. We water about every 2 weeks on average during warmer weather.

(Cautionary note for those that use city water with chlorine in it: chlorinated water will kill the micro-organisms in the compost and soil that you are working to help! If you have chlorinated water, either fill buckets and let them sit overnight to off-gas the chlorine or buy a chlorine filter that attaches to the garden hose to remove it. Thanks to Marguerite from IL for pointing this out!)

In our research and education of how to make great compost, we consistently saw traditional, proven methods from different countries, climates and approaches that worked. Many of them were very similar, adjusted to adapt to the particular environments of where they were used. The French intensive method used 3 feet of fresh horse manure and straw to heat the cold frames over the winter in Paris, then were pulled out and added to the compost piles to finish decomposing. In the fall the aged compost was added back to the growing beds for the upcoming winter. The Russian dacha gardening tradition shows how continuous composting and mulching with wood chips will improve the soil, overcoming both heavy winters in the north and drought conditions in the south.

Another thing that we found is that European traditions and older American traditions applied compost thickly, about 3 – 4 inches at a minimum, while modern gardening applies it rather thinly – like expensive imported marmalade on toast – and then wonder why they don’t get the results they expect.

After the year of aging and decomposing, our compost looks and smells like rich dark soil. This is especially pleasing to see in comparison to our pale tan native soils! Once we apply it to the garden beds, we mulch it with several inches of straw, watered well to keep it in place. Recently we have begun experimenting with wood chips as mulch, with good results. The wood chips help retain and gain moisture better than the straw, with the added benefit of attracting earthworms faster. The wood chips act like a layer of permeable insulation, attracting the cooler and moist early morning air that sheds its water when it meets the warmer temperature of the soil. This moisture travels into the soil and is retained. It is surprising to see and feel how moist the soil is under 2 – 3 inches of wood chip mulch when there has been no rainfall or drip irrigation at all!

Our approach to making the best compost possible is to combine or “stack” techniques, similar to the bio-tech industry, but it is much more effective with no worries about future side-effects! We will walk you through the different techniques we use and why we use them.

We have used straw bales as the container for our compost system for years, but have recently started using shipping pallets to more effectively utilize the composting area. The pallets are almost 3 times as tall as the straw bales and will give more compost in the same footprint. Wood chips are put down first, about 3 – 4 inches thick. These help retain moisture at the bottom of the pile before it seeps into the soil, as well as helping to attract earthworms and adding nutrients as they break down. We will scatter wood chips throughout the pile as we add horse manure. The nitrogen of the manure helps in the breakdown of the lignin in the wood chips, creating richer and more fertile compost.

Our two horses provide the bulk of the manure, along with the occasional load of cow manure. We are careful to get our cow manure from non-feedlot sources to avoid any contamination from antibiotics, glyphosate or industrial chemicals. This has supplied enough finished compost for our 14 thirty foot long raised bed garden that is our home and trial garden for our heirloom seed business. We apply compost twice a year, mid fall and early spring.

Straw is used to mulch the top of the pile and provides aeration as more manure is added to the top. About 1 – 2 inches of straw is added across the top about every two feet of depth. This is continued as the pile grows in height. As the straw bales that make up other bins start to fall apart, they are added to the new piles.

Milk is diluted 50/50 and sprayed on the pile to help feed the microorganisms and jump starts the decomposition process. The amino acids, proteins, enzymes and natural sugars that make milk a food for humans and animals are the same ingredients in nurturing healthy communities of microbes, fungi and beneficials in compost and garden soil. Raw milk is the best, as it hasn’t been exposed to heat that alters the components in milk that provide a perfect food for the soil and plants, but any milk will work. Using milk on crops and soils is an ancient technique that has been lost to modern industrial agriculture.

Molasses adds readily available sugars to the compost that will skyrocket the microbial activity, with the addition of needed mineral content. We use one cup of molasses to a gallon of water and spray onto the pile once it is about 1 – 2 feet tall.

Coffee grounds are added routinely as the pile builds to help with moisture retention and buffer our alkaline soils. Traditionally, coffee grounds were seen as an acidic addition but recent research shows that coffee grounds act more as a buffer, moderating either an acidic or alkaline pH toward a more neutral one. In arid regions coffee grounds can be added up to 25% by volume of the pile. They are a good nitrogen source to help keep the decomposition going as well as being a natural earthworm attractant! Sourcing the coffee grounds comes from local coffee houses, restaurants, Starbucks, etc.

Hardwood lump charcoal or Bio-Char is added as the pile grows to help the compost in many ways. The most obvious benefit is to add carbon to the soil. Charcoal has a lifetime benefit of several hundred years, as shown by Brazilian university studies on the Amazonian “Terra Preta” sites in the rainforest. It must be hardwood lump charcoal and not briquettes, which are processed with chemical fire accelerators, sawdust and other industrial waste. We like to crush it to about the size of a grain of corn to increase its surface area and effectiveness.

Charcoal acts like a sponge for the first 6 months or so, absorbing minerals and nutrients from the surrounding soil or compost while it “charges” or “activates”. After that it becomes an active beneficial component of the soil, providing housing and food sources for the microbial communities. Mycorrhizal Fungi will colonize charcoal and help to monitor the surrounding soil health, moving nutrients around as needed by plants. It was previously thought that mycorrhizae would only colonize the roots of plants, but it has been found that they will also inhabit charcoal. This will help them live throughout a winter when little root life or activity is present. The charcoal is sourced in 40 pound bags from buying clubs such as Costco or Sam’s Club, and can be obtained in larger quantities directly from the manufacturer.

Trace minerals are added such as Azomite or Elemite to increase the available mineral and trace elements that are often low in today’s feed. This helps the decomposition of the pile, is absorbed in the charcoal and carries over to help feed the garden soil.

Once the compost pile is at the top of the bin, we cover it with a generous layer of straw and build a new bin. Then we pretty much ignore the active pile except for watering when it needs it. Every couple of months we check the pile to see how it is progressing, and see how much it has started to drop in height. Once the pile is finished it will have dropped about 1/4 to 1/3 of its original height.

This system has evolved over several years to the present one and has continually produced better and better compost. This approach may sound like a lot of work, but with the system set up there is very little additional work after cleaning the horse pens. We usually get a full wheelbarrow of fresh manure every other day, and we rotate the addition of minerals, charcoal and wood chips on top of the wheelbarrow load which is then dumped onto the pile, putting the additions underneath the load. Once we have about 2 feet above the last straw layer, we add a few inches of straw. The scent of the active pile is that of a handful of rich fertile earth, so we gauge when to water when we can’t “smell the earth” as we walk by. The additional time needed to add to the nutrients range from the time it takes to add a couple of shovelfuls of wood chips or a scoop of Elemite to the wheelbarrow, to a couple of minutes to crush a few handfuls of charcoal.

No matter what your scale, from backyard home gardener to small acreage, these concepts can be scaled up or down to suit your particular needs and animals. Look to your neighborhood or community for feedstock and supplies for the compost pile. Most horse owners will be happy to give away their excess manure, as most do not compost it and it becomes a waste management issue. Some farms will have excess straw or broken bales that are not useful for them but would be excellent feed for your compost pile.

Good composting – like much of good agriculture – takes a certain amount of patience and observation, letting Mother Nature work her miracles on her schedule. Think about how nature decomposes and composts leaf litter in the forest or grasses in the pasture, they aren’t “done” in 30 to 60 days! Once the cycle is established, you will always have some great compost becoming available for the next feeding of your garden soil.

Fish Emulsion Feeds Your Plants

Fish emulsion has been a go-to product for the organic and natural home gardener for years now, as it has proven its effectiveness in feeding the soil and plants with biologically available nutrients while increasing soil and microbe health. The main drawback to commercial fish emulsion is the cost and the smell. While we can’t do anything to help you with the fishy smell, we can help you make your own fish emulsion that will not only save you a lot of money in product and shipping costs, but just might make a better product than you can buy! This homemade fish emulsion will almost always supply more nutrients than commercially available, but also supplies much more beneficial bacteria from the brewing process. In order to ship, commercial emulsions have little to no active bacteria, because they make containers swell as they continue to grow!

All fish emulsions are good organic nitrogen sources, but they also supply phosphorus, potassium, amino acids, proteins and trace elements or micro-nutrients that are really needed to provide deep nutrition to your soil community and plants. One of the benefits of fish emulsion is that they provide a slower release of nutrients into the soil without over-feeding all at once. It is usually applied as a soil drench, but some gardeners swear by using it as a foliar fertilizer as well.

Adding seaweed or kelp to the brewing process adds about 60 trace elements and natural growth hormones to the mix, really boosting the effectiveness of the fish emulsion. The seaweed or kelp transforms the emulsion into a complete biological fertilizer. Beneficial soil fungi love seaweed. Dried seaweed is available at most oriental grocery stores. The amount you need to add will depend entirely on your soil needs. If you are just getting started in improving your soil, add up to a cup of dried seaweed or 2 – 3 cups fresh. If your soil is doing pretty good then add about 1/4 to 1/2 cup of dried seaweed and up to 1 – 2 cups fresh.

Making Your Own Fish Emulsion

To make your own, obtain a dedicated 5 gallon bucket for this project. Trust me; you won’t want to use it for anything else once you’re done! Buy 10 cans of herring type fish such as sardines, mackerel or anchovies. Sourcing these from a dollar store or scratch and dent store makes perfect sense, as you don’t care about the can and aren’t going to eat them.

Rich, well-aged compost is a key ingredient to great fish emulsion, as it has lots of active microbes and other biological life which will help kick-start the fermentation of the fish. A good compost hunting dog is not required, but really helps. We’ve found the Doberman breed to be very helpful in finding just the right compost! Dalmatians do a pretty good job as well.

Fill the bucket half full of well-aged compost, aged sawdust or leaves, or a combination of all three. You are looking for the dark brown, crumbly compost that smells like rich earth.

Add water to about 2 inches from the top…

add in the cans of fish, rinsing the cans with the water to make sure you get every last drop of the “good stuff”. The juices or oils in the can will breed beneficial microbes and supply extra proteins.

To supercharge the brew, add 1/4 to 1/2 cup of blackstrap molasses to provide sugars and minerals to the fermenting process. The sugars also help control odors. Next, add the chopped or powdered seaweed to the mix. If you need extra sulfur and magnesium, add 1 Tbs Epsom salts.

Stir well and cover with a lid to control the odor, but not tightly as it will build pressure as it brews.

Be Careful!

NOTE – Make sure that flies do not get into the bucket or you will have a marvelous breeding ground for maggots! One solution is to drill several holes in the lid for the bucket and glue screen mesh on the inside of the lid, allowing air flow but keeping those pesky flies out. Remember, you are brewing the most delicious aromas the flies have ever smelled!

Let it Ferment

Let it brew for at least 2 weeks, a month is better. Give the contents a good stir every couple of days.

Once it has brewed for a month, it is ready for use!

There are a lot of ways to use this brew, so be creative. Some folks will strain off the solids, put them in the compost pile and use the liquid as a concentrated “tea” to be diluted with water. Others keep everything together and stir the mix well before taking what they need. What you have is a supply of bio-available nutrients in a soluble form.

Use as a Soil Drench and Foliar Fertilizer

For a soil drench, use 2 – 3 Tbs per gallon of water and apply to the roots on a monthly basis during the growing season. 1 Tbs per gallon of water makes a good foliar fertilizer. Just make sure to apply it by misting during the cooler parts of the day, not drenching the leaves in the heat. Half a cup per gallon will give your compost pile a kick start.

This brew will keep for at least a year, but you might want to make fresh each season. If you need less than 5 gallons, halve or quarter the recipe. It will smell, so store it where the odor won’t knock you out. I don’t trust the “deodorized” fish emulsions, as to remove the odor, some component of the fish product was removed either physically or chemically and is no longer available as a nutrient.

Fresh Coffee Grounds Are Great Source of Minerals and Nutrients

Looking to perk up your compost pile? Do you drink coffee? You might be holding the answer in your hands this very moment, or at least part of the answer. Coffee grounds have been used for many years by those “in the know” to boost the quality of their compost, making a superior soil amendment for free. The grounds are considered part of the “green” portion of the composting, speeding up the decomposition process while keeping temperatures high enough to kill off pathogens.

Coffee grounds provide energy in the form of nitrogen to the hard working bacteria doing all of the work in the compost. They also encourage beneficial microbe growth, contributing to a healthier soil. Another benefit is the minerals added to the compost such as phosphorus, potassium, magnesium and copper – all very necessary to the growing process. Earthworms absolutely love coffee grounds, preferring them to other food sources and turning them into highly prized vermicompost. For many years coffee grounds have been thought of as slightly acidic, but recent research shows that the grounds are usually pretty neutral in pH, but have a very high buffering capacity. This means that whether the soil is acidic or alkaline, the grounds will bring the pH back toward neutral, so they are good for any soil types. The moisture holding ability is very beneficial for loose soils, yet it acts to loosen heavy clay soils at the same time.

Some gardeners have worked the grounds directly into the soil, but it is best to add them to the compost pile and let decomposition release their nutrients first, then add the aged compost to the garden soil, working it into the top 2 – 3 inches in early spring and late fall. The grounds can make up to 25% by volume of the compost, and be used as a manure replacement for gardeners who don’t have ready access to those sources. Some city gardeners make their compost of leaves, cardboard and newspapers for the carbon side with coffee grounds and fresh grass clippings supplying the nitrogen to keep the pile going. It is best to let the compost decompose or age for at least 6 months, with a year time-frame yielding a higher quality amendment that looks very much like soil all by itself.

“Can raw milk make grass grow? More specifically, can one application of three gallons of raw milk on an acre of land produce a large amount of grass?”

David Wetzel is the person possibly most responsible for bringing the ancient practice of applying milk to the soil in order to improve the health, disease resistance, and productivity of the soil. As part of a 10-year study in collaboration with the University of Nebraska soil specialists and weed specialists as well as insect specialists have proven the effectiveness of milk as a soil improver.

It started with David having excess skim milk that he didn’t want to waste, so he started applying it to a pasture on his farm and noticed several oddities about that particular pasture. When his dairy herd was turned out on it, the butterfat content of the milk increased by 3-4% within 2-3 days of being in that pasture, every time. Not only that, but the herd needed fewer vet visits, maintained their weight better and the pasture recovered faster and produced more hay than other pastures. David contacted his next-door neighbor, Terry Gompert, an extension agent for the University of Nebraska about the phenomenon, and a multiple-year study was born. One of the additional benefits of spraying the milk has been a drastic reduction in grasshopper populations in the pastures, as the milk sugars are toxic to soft-bodied insects. One theory is that grasshoppers will leave healthy plants alone, as the milk feeds the plant as well as the soil.

The following article is from Ralph Voss, a student of David’s methods, followed by David’s own observations on what is working on his farm.

Mon, 2010-03-08

“This article appeared in the March 10, 2010, issue of theUnterrified Democrat, a weekly newspaper published in Linn, Mo., since 1866. In addition to writing for the paper, Voss raises registered South Poll cattle on pathetically poor grass that he is trying desperately to improve.”

Nebraska dairyman applies raw milk to pastures and watches the grass grow

An Illinois steel-company executive turned Nebraska dairyman has stumbled onto an amazingly low-cost way to grow high-quality grass – and probably even crops – on depleted soil.

Can raw milk make grass grow? More specifically, can one application of three gallons of raw milk on an acre of land produce a large amount of grass?

The answer to both questions is yes.

Call it the Nebraska Plan or call it the raw milk strategy or call it downright amazing, but the fact is Nebraska dairyman David Wetzel is producing high-quality grass by applying raw milk to his fields and a Nebraska Extension agent has confirmed the dairyman’s accomplishments.

David Wetzel is not your ordinary dairyman, nor is Terry Gompert your ordinary Extension agent. Ten years ago Wetzel was winding up a five-year stint as the vice president of an Illinois steel company and felt the need to get out of the corporate rat race. At first he and his wife thought they would purchase a resort, but he then decided on a farm because he liked to work with his hands. The Wetzels bought a 320 acre farm in Page, Neb., in the northeast part of the state, and moved to the farm on New Year’s Day in 2000.

“We had to figure out what to do with the farm,” Wetzel said, “so we took a class from Terry Gompert.” They were advised to start a grass-based dairy and that’s what they did. “There’s no money in farming unless you’re huge,” Wetzel said, or unless the farmer develops specialty products, which is what they did.

In their business, the Wetzels used the fats in the milk and the skim milk was a waste product. “We had a lot of extra skim milk and we started dumping it on our fields,” Wetzel said. “At first we had a tank and drove it up and down the fields with the spout open. Later we borrowed a neighbor’s sprayer.”

Sometime in the winter of 2002 they had arranged to have some soil samples taken by a fertilizer company and on the day company employees arrived to do the sampling, it was 15 below zero. To their astonishment they discovered the probe went right into the soil in the fields where raw milk had been applied. In other fields the probe would not penetrate at all.

“I didn’t realize what we had,” Wetzel said. “I had an inkling something was going on and I thought it was probably the right thing to do.” For a number of years he continued to apply the milk the same way he had been doing, but in recent years he has had a local fertilizer company spray a mixture that includes liquid molasses and liquid fish, as well as raw milk. In addition he spreads 100 to 200 pounds of lime each year.

Gompert, the extension agent that suggested Wetzel start a grass-based dairy, had always been nearby – literally. The two are neighbors and talk frequently. It was in 2005 that Gompert, with the help of university soils specialist Charles Shapiro and weed specialist Stevan Kenzevic, conducted a test to determine the effectiveness of what Wetzel had been doing.

That the raw milk had a big impact on the pasture was never in doubt, according to Gompert. “You could see by both the color and the volume of the grass that there was a big increase in production.” In the test the raw milk was sprayed on at four different rates – 3, 5, 10 and 20 gallons per acre – on four separate tracts of land. At the 3-gallon rate 17 gallons of water were mixed with the milk, while the 20-gallon rate was straight milk. Surprisingly the test showed no difference between the 3-, 5-, 10- and 20-gallon rates.

The test began with the spraying of the milk in mid-May, with mid-April being a reasonable target date here in central Missouri. Forty-five days later the 16 plots were clipped and an extra 1200 pounds of grass on a dry matter basis were shown to have been grown on the treated versus non-treated land. That’s phenomenal, but possibly even more amazing is the fact the porosity of the soil – that is, the ability to absorb water and air – was found to have doubled.

So what’s going on? Gompert and Wetzel are both convinced what we have here is microbial action. “When raw milk is applied to land that has been abused, it feeds what is left of the microbes, plus it introduces microbes to the soil,” Wetzel explained, adding that “In my calculations it is much more profitable (to put milk on his pastures) than to sell to any co-op for the price they are paying.”

Wetzel’s Observations

Wetzel has been applying raw milk to his fields for 10 years, and during that time has made the following observations:

* Raw milk can be sprayed on the ground or the grass; either will work.

* Spraying milk on land causes grasshoppers to disappear. The theory is that insects do not bother healthy plants,which are defined by how much sugar is in the plants. Insects (including grasshoppers) do not have a pancreas so they cannot process sugar. Milk is a wonderful source of sugar and the grasshoppers cannot handle the sugar. They die or leave as fast as their little hoppers can take them.

* Theory why milk works. The air is 78% nitrogen. God did not put this in the air for us but rather the plants. Raw milk feeds microbes/bugs in the soil. What do microbes need for growth? Protein, sugar, water, heat. Raw milk has one of the most complete amino acid (protein) structures known in a food. Raw milk has one of the best sugar complexes known in a food, including the natural enzyme structure to utilize these sugars. For explosive microbe growth the microbes utilize vitamin B and enzymes. What do you give a cow when the cow’s rumen is not functioning on all cylinders (the microbes are not working)? Many will give a vitamin B shot (natural farmers will give a mouthful of raw milk yogurt). Vitamin B is a super duper microbe stimulant. There is not a food that is more potent in the complete vitamin B complex than raw milk (this complex is destroyed with pasteurization). Raw milk is one of the best sources for enzymes, which break down food into more usable forms for both plants and microbes. (Again, pasteurization destroys enzyme systems.)

* Sodium in the soilis reduced by half. I assume this reflects damage from chemicals is broken down/cleaned up by the microbes and or enzymes.

* If you choose to buy raw milk from a neighbor to spread on your land, consider offering the farmer double or triple what he is paid to sell to the local dairy plant. Reward the dairy farmer as this will start a conversation and stir the pot. The cost for the milk, even at double or triple the price of conventional marketing, is still a very cheap soil enhancer.

* Encourage all to use their imagination to grow the potential applications of raw milk in agriculture, horticulture andthe like – even industrial uses –possibly waste water treatment.

Microbes

The purpose of this story is to convince farmers and livestock producers in this area to look into the possibility of using raw milk, compost tea, earthworm castings tea,liquid fishor sea minerals or some combination thereof to boost production at an affordable cost. It’s my experience that people in the Midwest are to a great extent unaware of the benefits of microbes. If the first part of this story has caught your attention and you intend to consider the use of raw milk or any of the other methods, you need to learn about microbes and the best way I have discovered is a book co-authored by Jeff Lowenfels and Wayne Lewis,Teaming with Microbes.

In this story I cannot go into detail about microbes, the miniscule little critters that exist in abundance in good soil. There are four principal types of microbes – bacteria, fungi, protozoa and nematodes. To get an example of their size, consider that there are a billion bacteria in one teaspoon of good soil. The role of microbes is to consume carbon, along with other minerals and nutrients, and these are stored in their cells until their ultimate release for use by plants. Microbes also store water, which make them drought-fighters as well.