Why do most pots fail in August? It’s not water; it’s physics. Discover the 5 engineering principles of regenerative container gardening—from “Thermal Jackets” to “Wicking Beds”—and learn how to build a living soil system that thrives in the heat.

Tag Archive for: Soil Health

Soil Elixir Jump-Starts Your Garden’s Soil

One of the most anticipated times of year for gardeners is Spring, with the attendant planting season. Everything is new and fresh, a chance to start over and improve on last year’s garden. A big subject for gardeners is what to do with the soil to prepare it for planting. If you have been reading our articles over the past several years, you know we advocate building the health and vitality of the soil in a natural, biologically safe manner. Soil becomes healthier, more productive, and disease, weed, and pest resistant. It results in an upward spiral where the garden gets better year after year.

Here is a unique recipe for a spring garden elixir that is easy to mix, completely non-toxic, and hugely beneficial for jump-starting your garden’s soil and getting it ready for planting. It comes courtesy of Crop Services International, which has over 35 years of experience helping growers accomplish their goals. They provide a Non-Toxic/Biological/Sustainable approach to growing food, from a full-scale commercial farm to the home gardener. We have read “The Non-Toxic Farming Handbook,” which they wrote to educate ourselves on improving our knowledge and approach.

This recipe is based on a 20′ x 50′ garden or 1000 sq. ft. Adjust for your garden size.

Before You Start

This recipe and applications assume an average garden soil that is basically good but could use some help.

It works in fertile soils by subtracting the lime or gypsum application, adding compost before spraying the elixir.

It helps very poor soils, but won’t give as much effect.

Preparing your garden beds for the elixir will require a couple of things.

First, evenly spread a 50 lb bag of high calcium lime (for acidic soils) or gypsum (for alkaline soils) across your beds. Your local garden center should have this. If using lime, it should be high calcium lime with as low magnesium as possible. 5% or less is great, up to 10% is acceptable, but nothing over 10%. The higher magnesium percentage releases excess nitrogen into your soil, greatly decreasing its fertility. It also overloads both the chemical and biological processes of your soil. Do not buy Dolomite lime, as it has too much magnesium.

Then, follow with 100 lbs of rich, aged compost, spread evenly across your beds, about 2 full-sized wheelbarrows. This can be purchased or from your own compost pile. Again, the best is made by you, and it is easy – “Compost – Nourishing Your Garden Soil” has all the details.

After doing both of these, make and apply the elixir.

Notes on Ingredients

- When purchasing the fish fertilizer, if you can find one with kelp or seaweed, even better. If you want the absolute best fish emulsion possible, brew your own! Read our “Best Homemade Fish Emulsion” for the recipe and instructions.

- Blackstrap molasses is best for its increased mineral content. Unsulphured is preferred but not absolutely necessary. One of the best sources of inexpensive molasses is a feed store that supplies horses, which can be bought by the gallon for much less than at a supermarket.

- Do not buy diet cola, as the Aspartame/NutriSweet used as the sweetener acts as a chelating agent, meaning it ties up the minerals and nutrients in the soil, making them unavailable to the plants. (It also does the same thing in your body!) The cola has Phosphorus to add to the mix along with sugars.

- The beer adds B vitamins – no, not vitamin Beer!

- The Borax powder adds Boron, one of the most important elements in the biochemical sequence of plant growth.

- Cranberry juice is full of vitamins and minerals, acts as an antibacterial agent, and has an acidic pH. Depending on how the juice is processed, it can also contain significant amino acids.

This recipe is based on a 20′ x 50′ garden or 1000 sq. ft. Adjust for your garden size.

- 20-24 oz liquid fish fertilizer Home-made is best

- 1/2 cup molasses Black strap has more nutrients

- 16 oz bottle of cola – NOT DIET!

- 24 oz beer 2 - 12 oz cans, any beer works

- 1/2 cup Borax powder

- 1 qt cranberry juice – make sure to get 100% cranberry juice, not a dilution

- Mix well with a stirrer and thin with enough water to enable mixture to be sprayed with a tank type or hose-end sprayer.

Apply the mix evenly over lime or gypsum and compost base with sprayer. If needed, go back over with second application to use up all of the batch, just make sure to apply evenly.

Broad-fork or lightly rototill garden soil. If using a rototiller, don’t go more than 2 inches deep at the maximum. Most of the biological growth happens at the 2-3 inch mark and the soil is turned over an inch or so beyond what the tines reach. Tilling deeper only destroys microbial life in the soil, setting you back in your efforts to create and build biologically active soil.

It must be noted that the sprayer cannot have been used to spray any chemical treatments like herbicides, pesticides, etc. as this will put those chemicals onto your soil, killing the microbial life in the soil and feeding the chemicals to the plants, where you wind up eating them!

Seed Planting Elixir

Once you have applied the elixir and broad-forked or lightly tilled the soil, prepare your garden planning and seedlings. We have another planting elixir to use just after planting the seeds and transplanting the seedlings into the garden that we’ll share with you: In a gallon milk jug, mix 1/2 cup of fish emulsion, 1 tsp sugar (preferably raw or brown), and 1/2 cup of cola. Fill the jug with water and shake well. Apply the mixture over the seeds and transplants. Each gallon will treat approximately a 50-foot row.

This is a great start towards sustainable, biological agriculture in your own garden. Remember, though, it is just a start, a good step in the right direction. To continue to make progress in knowledge and soil health, you need to find out where you are starting from. Do more reading, ask questions, and get a complete soil analysis, not just the widely offered NPK and pH soil tests. Spend the money to find out exactly where your garden soil is, and then you can make sound decisions on where you want and need to go. Then you won’t be guessing and shooting in the dark, trying to do what is right but not really knowing if you are making positive progress.

Soil Builder vs Garden Cover Up Mix – which is best for your garden?

Both of our cover crop mixes give you multiple benefits in the soil and above it. You can’t go wrong with either one. The Garden Cover Up mix is a general use cover crop, while the Soil Builder mix is more specific toward improving the overall condition of your soil.

Cover crops improve soil in a number of ways. They protect against erosion while increasing organic matter and catch nutrients before they can leach out of the soil. Legumes add nitrogen to the soil. Their roots help unlock nutrients, converting them to more available forms. Cover crops provide habitat or food source for important soil organisms, break up compacted soil layers, help dry out wet soils and maintain soil moisture in arid climates.

It’s always a good idea to maintain year-round soil cover whenever possible, and cover crops are the best way.

Let’s look at how cover crops work overall, then we’ll see the differences of each mix.

Most cover crop mixes are legumes and grains or grasses. Each one has a different benefit to the soil. Legumes include alfalfa, clover, peas, beans, lentils, soybeans and peanuts. Well-known grains are wheat, rye, barley and oats which are used as grasses for animal forage.

Legumes

Legumes help reduce or prevent erosion, produce biomass, suppress weeds and add organic matter to the soil. They also attract beneficial insects, but are most well-known for fixing nitrogen from the air into the soil in a plant-friendly form. They are generally lower in carbon and higher in nitrogen than grasses, so they break down faster releasing their nutrients sooner. Weed control may not last as long as an equivalent amount of grass residue. Legumes do not increase soil organic matter as much as grains or grasses. Their ground cover makes for good weed control, as well as benefiting other cover crops.

Grains or grasses

Grain or grass cover crops help retain nutrients–especially nitrogen–left over from a previous crop, reduce or prevent erosion and suppress weeds. They produce large amounts of mulch residue and add organic matter above and below the soil, reducing erosion and suppressing weeds. They are higher in carbon than legumes, breaking down slower resulting in longer-lasting mulch residue. This releases the nutrients over a longer time, complementing the faster-acting release of the legumes.

This pretty well describes what our Garden Cover Up mix does, as it is made up of 70% legumes and 30% grasses.

Our Soil Builder mix takes this approach a couple of steps further in the soil improvement direction with the addition of several varieties known for their benefits to the soil structure, micro-organisms or overall fertility.

For example, the mung bean is a legume used for nitrogen fixation and improving the mycorrhizal populations, which increase the amount of nutrients available to each plant through its roots.

Sunflowers are renowned for their prolific root systems and ability to soak up residual nutrients out of reach for other commonly used covers or crops. The bright colors attract pollinators and beneficials such as bees, damsel bugs, lacewings, hoverflies, minute pirate bugs, and non-stinging parasitic wasps.

Safflower has an exceptionally deep taproot reaching down 8-10 feet, breaking up hard pans, encouraging water and air movement into the soil and scavenging nutrients from depths unreachable to most crops. It does all of this while being resistant to all root lesion nematodes. Gardeners growing safflower usually see low pest pressure and an increase in beneficials such as spiders, ladybugs and lacewings.

Now you see why you can’t go wrong in choosing one of our cover crop mixes! Both greatly increase the health and fertility of the soil, along with above-ground improvements in a short time. Even if you only have a month, the Garden Cover Up mix will impress you for the next planting season.

For a general approach with soils that need a boost but are still producing well, the Garden Cover Up mix is the best choice. Our Soil Builder mix is for rejuvenating a dormant bed or giving some intensive care to a soil that has struggled lately. Both will give you a serious head start in establishing a new growing area, whether it is for trees, shrubs, flowers, herbs or vegetables.

Let one of our cover crops go to bat for you and see what happens when you play on Mother Nature’s team!

Potting soils come in all shapes and sizes, with most touting some form of “Organic & Natural” on the bag – but are they really certified organic? Do those potting soils really work as advertised and contain healthy, wholesome ingredients to help your precious seedlings get that critical head start they need?

To answer these questions and more, we bought a few bags of potting soils from our local sources, brought them home and opened them up to take a close look at what is there. We looked at the bag and labeling, seeing what is being sold and why, what wording and marketing is being used and if they stood up to closer scrutiny. One of those potting soils we have used for a few years, so we let you know of our past experiences.

Please note – this article is in no way meant to be a comprehensive, exhaustive laboratory research and review of all potting soils available to the average home gardener. There’s just no way for us to do that, as many are only regionally available and the ingredients change from region to region in the bigger brands.

As with our seed starting mixes article, we suspect there are a few companies producing potting soils for different markets with unique branding and bagging for each channel. We saw this with one product – one bag design and color set for the big box stores and another one for the smaller independent garden centers. This only underscores the need to read the labels, know what the descriptions, ingredients and marketing-speak mean and be able to decide for yourself if that particular bag will work for you and is worth the cost.

As with our seed starting mixes analysis, we found confusing and sometimes misleading labeling.

What are potting soils and do I need to use one?

Potting soils are traditionally what seedlings are transplanted into from the seed starting mixes. The seed is germinated in the seed starting mix, then when it is 3 – 4 inches tall and starting to put on its second or third set of true leaves, it is transplanted into a potting soil. Potting soils have nutrients which are missing in the seed starting mixes, continuing the growth of the seedling by feeding and supporting the root structure it is starting to develop.

What goes into potting soils varies widely, from a basic seed starting mix with some aged compost added for plant nutrition to full custom blends with compost, soil and nutrients coming from different ingredients – all to supposedly help the seedling grow stronger and faster.

Not everyone needs potting soils, as some have the space and materials availability to create an excellent rich, aged compost to use as the starting point of mixing their own special blend, while others just don’t have the time, space or materials available to do that.

Let’s take a look!

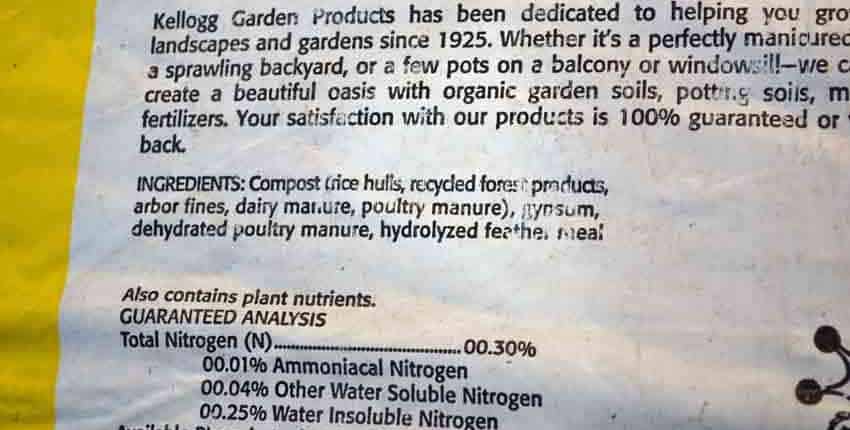

The first of the potting soils we found was the Kellogg Amend Organic Plus at Lowe’s and it’s available at Home Depot as well, so it should be available in most big box stores in the western US. We were interested to see what was in the bag and do some testing, as we’ve had several of our customers email us in alarm after transplanting into the Amend potting soils and within a few hours the seedlings were almost all dead or severely wilted. We found a commonality with most of them using the Kellogg Amend potting soils, but haven’t heard anything negative in the past couple of years.

As we mentioned in our seed starting mix article, we are not impressed with the words “Organic” or “Natural” on bags of soil, so seeing “Organic Plus” prominently splashed across the bag was an alert for us. It is branded as a garden soil for flowers and vegetables.

One label that did catch our eye and add to the intrigue was the OMRI listing on the bottom left of the bag. This indicates the contents are certified for organic food production, and are the equivalent of a “Certified Organic” label on food.

The OMRI label piqued our curiosity because our previous research as to why the Amend potting soils were killing seedlings led us to the fact that Kellogg had been using bio-solids, or treated municipal sewage, and possibly industrial runoff or wastewater. This easily explained why the seedlings died when transplanted into the potting soil.

So the question was – is this the same potting/garden soil, and if so, how is it OMRI listed?

In doing some reading, it appears Kellogg has used bio-solids or treated municipal sewage as a major ingredient in its composting program for a number of years. It seems that their OMRI listed products do not have any bio-solids as an ingredient in their products, but you can’t tell from the label.

In looking at the OMRI listing for Kellogg Amend garden soil, we found it is listed but with restrictions. OMRI lists it in the category of “Fertilizers, Blended with micronutrients” with the restriction being –

May be used only in cases where soil or plant nutrient deficiency for the synthetic micronutrients being applied is documented by soil or tissue testing.

Kellogg’s Amend product page has this to say about their OMRI listing –

Proven Organic

All of our products are listed by the Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI), the leading non-profit, internationally recognized third party accredited by the USDA’s National Organic Program (NOP). That means every ingredient and every process that goes into making our products has been verified 100% compliant as organic, all the way to the original source. Look for the OMRI logo on the bag, ensuring every product is proven organic.

All in all, it is OMRI listed – even with the discrepancies between Kellogg’s product information and the OMRI listing itself with the restrictions.

The OMRI listing is displayed in the lower left part of the bag, underneath the info box of what it is supposedly derived from and what it is good to use it for.

The ingredients list compost as the primary ingredient with what makes up the compost. Recycled forest products are typically a blend of finely ground wood from leftovers of the timber industry. Arbor fines are finely ground tree trimmings. Hydrolyzed feather meal is crushed and boiled poultry feathers, used as a source of nitrogen.

Dairy and poultry manure sound fine, until the source is looked at a little closer. What is the source of the dairy and the poultry manure? There is reasonable concern as to what is contained in the manure of animals from confined feeding operations – there are antibiotics and hormones used in the day to day operations which are passed through in their manure. Another concern is the possible presence of industrial herbicides and pesticides used in conventional grain production, which can easily be passed into the manure.

These are things to think about, especially if you want to grow as organically as possible.

One of our biggest initial concerns after getting it home and looking up both the Kellogg’s product listing page and the OMRI listing showing the restriction is there is no mention anywhere of the “synthetic micronutrients” from the OMRI listing on the bag or Kellogg’s website.

What are those synthetic micronutrients, and what is their source?

On opening the bag we noticed it was moist and had some white mold spots on the woody material in the mix. This is not a bad thing, molds and fungi work to break down wood into more available nutrients. Woody material helps to boost microbial activity to do just this.

The bag had a rich, woody aroma but did not smell of raw or partially decomposed manure. It was a dark, rich brown verging into almost black.

A handful of the soil felt light and porous with a slightly damp feeling to it. There was a trace of dark residue left on the fingers after rolling a handful through the fingers and getting a feeling for it.

On closer inspection, it is easy to see the woody residue of various sizes. Even though it is advertised as a soil, it was fairly light in texture without the more solid structure needed for long term growing of plants.

The white mold can be seen in the top right of the photo.

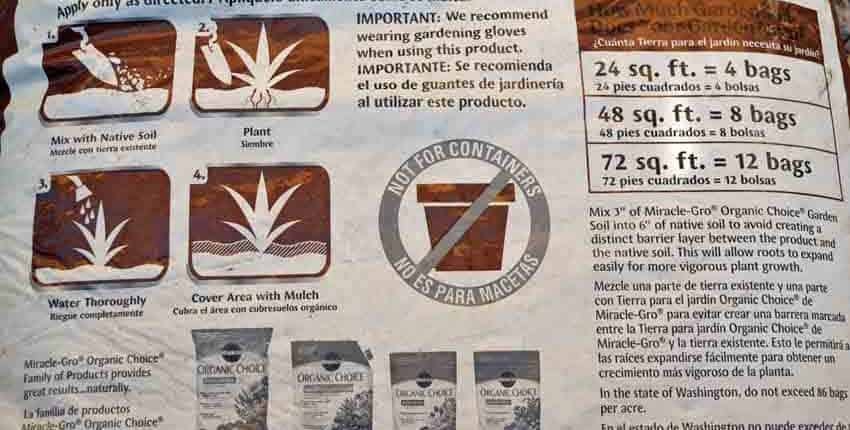

The next bag we opened was Miracle-Gro Organic Choice. We also picked this up at Lowe’s and have seen an impressive selection of Miracle-Gro products at Home Depot as well, so any big box store will have this line. We’ve also seen this brand at every garden center, hardware store garden aisle and landscaping supply store we’ve visited. It’s hard not to find them.

Again, the word “Organic” is used as a marketing tool in the word choice for the name. This is advertised for use with in-ground vegetables, fruits, flowers and herbs. It has the “Natural & Organic” term next, above a statement that it will grow fresh vegetables in your backyard.

So far, pretty standard stuff and not really any different than the next pile of bags at the big box store.

Our concern with this Miracle-Gro product is much the same as we mentioned in our Seed Starting Mix article -their blend of plant food emphasizes vegetative growth and strong flowering, without the nutrients for fruit or food production. We have seen numerous gardeners with tomato plants growing lush, dark green leaves and covered in flowers but not producing a single tomato, or very few.

Looking at the back of the bag, we were surprised to see this product was not recommended for container gardening. It is also interesting to see the warning to wear gloves when using Organic Choice.

It’s labeled as “garden soil” on the front, but on the back the instructions say to mix 3″ of Organic Choice with 6″ of native soil, mix well to avoid a stratified layer, then plant. These instructions combined with the not for containers seems to indicate this is not a full potting soil and more of a soil amendment or fertilizer.

The ingredients listing says it is formulated with organic materials but doesn’t specify if “organic” means organic as in containing carbon, or organic as in certified organic.

It has much the same ingredients – forest products, compost, composted manure and pasteurized poultry litter. In addition it lists peat humus and sphagnum peat moss which are more commonly associated with seed starting mixes than potting soils.

The ingredients do vary regionally, which they do specify.

We searched the OMRI listing to see if this, or any, Miracle-Gro product was listed and found this is OMRI listed, along with several other products. This is somewhat surprising, as most other manufacturers proudly display the OMRI listing label. Another interesting detail is this has no restrictions, unlike Kellogg’s Amend. It is listed under fertilizer and soil amendments, which makes more sense of the instructions to mix with native soil.

On opening the bag we noticed it was moist with a dark brown, rich earth color. There was woody material present, but seemed a bit more integrated and had an earthy, soil based aroma. There was no indication of partially composted manure or off odors.

It didn’t have any mold indication and a handful of the soil had more of a substance to the texture, while still being light and fluffy. There were smaller or finer components to the mixture. There was less of a dark residue on the fingers after handling a handful for inspection.

Closer inspection shows the more even distribution of size, along with the dark brown or earthy color. This seemed to be closer to a replacement soil but with enough lightness to allow good root development.

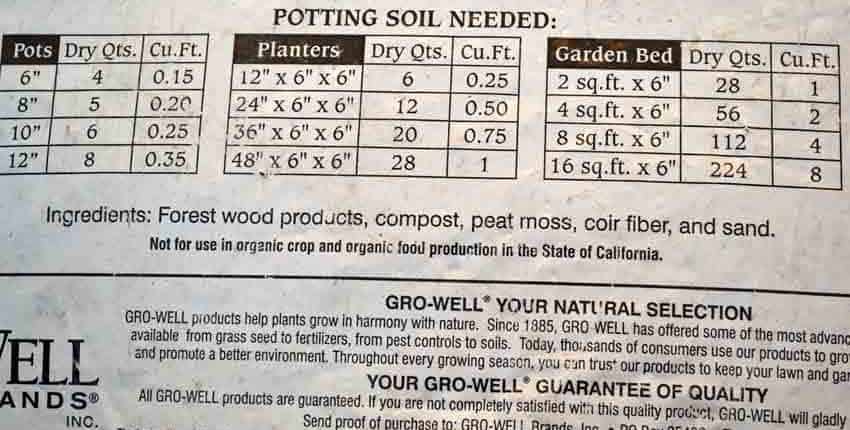

The next bag was Garden Time Square Foot Garden Soil from Gro-Well Brands. They are local to us, being based in Tempe, AZ. This was bought at Lowe’s and we’ve seen it at Home Depot also, and have seen garden forum threads where it is possible to special order it online in different quantities. We also saw it at our local True Value Hardware store in the garden aisle, with a different design bag – so it is probably also available in independent garden centers as well.

We have used this particular mix for a few years now with good results. We primarily use it as a seed starting mix and transplanting medium, but have experimented with it as a complete soil – like the bag’s labeling says – and have been pleased with the results.

Having said that, it isn’t perfect either and makes many of the same claims as the other brands. The “Natural & Organic” label is prominent on the bag, even though this is not OMRI listed. Some of the other claims are “Proven Formula for Optimum Growth” and “Great for Vegetables”. It does say “ready to use” and doesn’t need mixing with native soils, something that might be helpful for a container gardener with a small patio or apartment balcony.

The ingredients are compost, peat moss, coconut coir, vermiculite, bloodmeal, bone meal, kelp meal, cottonseed meal, alfalfa meal and worm castings. The peat moss, coir and vermiculite are classic seed starting mix ingredients, with the compost, different meals and worm castings adding nutrients to the soil for the plants growth and health. We use this as both a seed starting mix and potting soil or transplant soil because of the nutrients, which are lacking in straight seed starting mixes.

The same concern we voiced above at the vagueness of what is in the compost is valid here as well. In reading around a bit, I haven’t come across Gro-Well Brands using bio-solids in their compost, which is good news. On the other hand, that doesn’t mean the compost is organically sourced and not feedlot manure, but it’s a step in the right direction.

The more extensive list of ingredients give this some substance in nutrition so it can be used as a transplanting medium, a potting soil or as a complete standalone soil.

As another plus, we’ve not experienced seedlings dying when transplanted into this mix, nor have our customers said anything.

On opening the bag, the soil is slightly moist with a very dark, almost black color. It had almost no odor and felt light in weight but with some substance. This makes sense with the compost being 30 – 40% and much of the rest made up of lighter weight seed starting ingredients that have no odor of their own. The shiny vermiculite specks are easy to see and the texture is fairly even without lots of larger, identifiable chunks of wood.

A handful of the soil showed more of the smaller size particles making up the mix with an even and light feel to it. There was a trace of black residue on the fingers after a handful for inspection.

A closer inspection shows the darker color, with the specks of vermiculite showing through.

The last bag was also from Gro-Well Brands – Garden Time Potting Soil. This was also bought from Lowe’s, and is available in big box stores. It may be regionally available in independent garden centers with a different bag.

The same technique of word use – “Natural & Organic” was in play, but the other trigger words were missing. This is advertised as an all-purpose potting soil for indoor and outdoor use in containers and garden beds, as well as for transplanting.

Like the Square Foot Gardening soil, this is not OMRI listed.

The ingredients are different, with fewer of the seed starting ingredients and less of the nutrient amendments. It does have peat moss and coconut coir fiber, common in seed starting mixes, but is without the perlite and such.

The standard forest wood products are there, as well as the compost listing again. What we found interesting is the addition of sand as the last ingredient.

When opening the bag we noticed this mix had a more woody aroma and was less earthy. It was also the driest of the mixes, leaving almost no residue on the hand after sifting through a handful of mix. It wasn’t dry, just much less moist than the other mixes. It had more substance and weight to the mix, probably as a result of the sand. This mix looked, smelled and felt the woodiest of the ones we inspected. It had no odor of compost or manure at all, only slightly of decomposed wood.

One thing we immediately noticed with a handful of soil is the white specks in the mix. In looking closely at them, they look much like perlite even though there is none listed on the ingredients. This could be an older bag with a new mix formulation, or a mistake in adding perlite to this mix. The perlite isn’t a negative, but the fact it isn’t listed in the ingredients makes us wonder a bit.

Even with this, the mix looks like it would be good as an amendment to loosen up native soils. The overly woody composition would be beneficial as it decomposed more, but might not add much to this season’s growth.

A closer look shows the woody texture and color with the white specks of what looks to be perlite throughout.

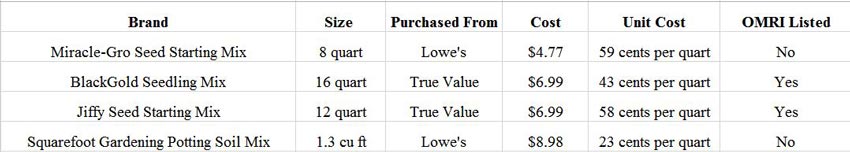

In looking at the related costs, a couple of things stand out. The two best-looking soil mixes are also the most expensive – Miracle-Gro and the Square Foot Gardening Soil. They are also the smallest size bags. When adding in the positive benefits of an OMRI listing, the Miracle-Gro becomes the initial winner – something that surprised us.

In making a recommendation, an OMRI listing helps to assure a home gardener that the materials and ingredients used are of better quality and higher nutrient content than a non-listed mix. With that said, we would not recommend avoiding mixes which aren’t listed if you can be sure the ingredients meet reasonable standards. For example, compost from a neighborhood friend’s horses won’t be able to be OMRI listed, but would probably be excellent compost if the horses are fed well and wholesomely. The same would go for a grass-fed farmer in your area, who doesn’t feed growth hormones or regular antibiotics.

From this list, our two choices are the Miracle-Gro Organic Choice Garden Soil and the Square Foot Gardening Soil, with the others being a distant second choice if the first two weren’t available. This is conditional upon our testing some seedlings in each of these to see if they can actually support healthy seedling growth, but that will be another article!

For you, the best choice depends on what is available in your area, the amount of potting soil needed and what you can afford. Some gardeners, like ourselves, much prefer to make our own compost with multiple amendments to create a complex and wonderfully fertile soil amendment, while others simply don’t have the space or availability of materials. Some better options include creating a composting system as part of a community garden, or partnering with a friend or neighbor who has the space and is willing to boost their garden’s fertility. You might offer to do the work in setting up and maintaining the compost in return for some of the finished product for your garden.

Now you’ve got an overview of what to look for and be aware of when shopping for potting mixes, what are your thoughts and experiences? Do you have a dependable “go-to” potting mix you’ve used and loved for years? Or, do you have a tried and true recipe for mixing up your own potting soil that has never let you down? Please share!

Seed starting mixes can be confusing – there are so many at different price points; who’s to know what’s good and what’s junk? Is the extra expense worth it, or is the cheapest mix just as good?

We looked at a few examples on the market to see what is available from a range of prices and suppliers. Starting with the big box stores and going to a local hardware store with a good gardening selection and then to a garden center, we chose a representative sample to give you a good starting point in choosing what to use for your seed starting.

This is in no way meant to be an exhaustive or comprehensive review of all available seed starting mixes. From what we can tell, there are many different brands and types of seed starting mixes. We suspect that a few companies are producing many of the re-bagged or re-branded mixes, much like there are exactly two car battery manufacturers in the US, selling dozens of brands of batteries through different outlets. Our goal is to provide you with an educated overview of some middle of the road seed starting mixes so you will be better informed when confronted with the “Great Wall” of seed starting mixes at your local garden center.

Along the way, we found seed starting mixes are seemingly designed to be confusing – especially when they are stacked next to each other in the garden section of the big box store or in the garden center. None of them were the same size, so easily comparing costs while in the store was difficult, requiring converting different prices to the same volume. We chose a quart size as the standard for the seed starting mixes, as most home gardeners will be using smaller amounts than market growers.

Another interesting thing we found was the labeling on each bag and the claims made. Some had the word “Organic” prominently displayed or used as part of the name, with no verification that the contents were, in fact, organic. “Natural” was also strongly used, with no substantiation.

In addition to the seed starting mixes, we have included a potting mix we’ve started seeds in for several years and have recommended to our customers. This is included as a reference point, as gardeners in some areas won’t be able to use a potting soil to start seeds due to high humidity and the associated fungi and mold challenges. Others, like us, will be able to use it to their advantage.

What are seed starting mixes and do I need one?

Seed starting mixes are not soil, they are blended to create a good environment to get the seed germinated and into the seedling stage, where it is transplanted into a potting soil or garden soil. For a closer look at the components that typically make up seed starting mixes, read Seed Starting Media for the Home Gardener.

Not everyone needs seed starting mixes, some gardeners do very well starting their seeds in potting soil or a rich garden soil. This often saves the work and stress of transplanting, but if you need a sterile soil because of mold or fungi pressures, then seed starting mixes will really help. Other gardeners just trust a sterile seed starting mix and have had good results for their garden.

Let’s take a look!

For all of the photos, click to enlarge them for more detail.

First up is Jiffy “Natural & Organic” Seed Starting Mix. We bought this at our local True Value garden center, so it should be available at independent garden centers and possibly the big box stores. There are several interesting things about this seed starting mix. First off, there is no ingredients listed, either on the bag or on Jiffy’s website. Second, this is an OMRI listed product, meaning it is approved through the Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI).

OMRI is an international nonprofit organization which certifies which input (fertilizer, herbicide, pesticide, etc.) products are allowed for use in certified organic agriculture. OMRI Listed® products are allowed for use in certified organic operations under the USDA National Organic Program. This is a big deal, there is no way to buy or sneak a product in and most companies will prominently display the OMRI listing on their bags, as you’ll see below.

Jiffy doesn’t mention it, or list the ingredients. With the OMRI listing, we feel pretty comfortable in using this, but would like to see what makes up the seed starting mix.

Here is what the bag looks like. On first read the “Natural & Organic” label is somewhat misleading, especially with no mention of the OMRI listing. The bag has 12 quarts for $6.99, so not a bad price, especially for a smaller home gardener who will use less than one bag to start their tomato, pepper and eggplant seeds.

An initial look at the soil shows what looks to be some coconut coir, possibly some peat moss, perlite and maybe some compost, but it’s hard to be sure. It had a good, rich soil aroma and was finely textured with no large lumps or woody chunks in it.

Here’s a closer inspection.

Overall, we were pleased at what we saw, with the caveat of wishing to know what the ingredients were making up the mix. On the plus side, OMRI listing is very good – indicating it is accepted for certified organic agriculture.

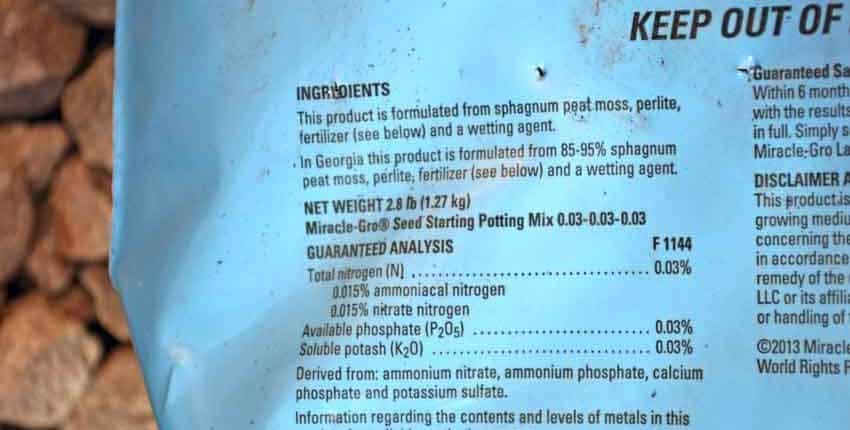

Miracle Gro Seed Starting Potting Mix was next up. The labeling seems to be trying to straddle the seed starting mix/ potting soil applications without specifying if it is suitable for both. The bag says it is enriched with Miracle Gro, which is no surprise, and the mix is excellent for starting cuttings. The bag has 8 quarts and is $4.77 at Lowe’s or Home Depot, which is enough for a small gardener to start seeds with. This mix is not OMRI listed. Here is Miracle Gro’s online listing.

Our concern with Miracle Gro is their blend of plant food emphasizes vegetative growth and strong flowering, without the nutrients for fruit or food production. We have had numerous customers call or email asking why their tomato plants had such lush, dark green leaves and were covered in flowers but not producing a single tomato, or very few. When we asked if they were using Miracle Gro, they seemed shocked that we could know what they were using!

The ingredients are listed – peat moss, perlite, Miracle Gro fertilizer and a wetting agent. Not terrible, but not the greatest either. If you’ve read Starting Seeds at Home – a Deeper Look, you remember that during germination, seeds have no need for fertilizers as they carry everything they need to sprout and establish a seedling inside the seed coat. The fertilizer might be beneficial during the seedling phase, but more soil nutrients are definitely needed to sustain a healthy plant, so this is not a seed to garden transplant mix. The wetting agent will be beneficial in the germination stage, but could contribute to mold and fungal issues for the seedling if the gardener isn’t aware and careful in not over watering and inadvertently saturating the soil, which the wetting agents will make worse.

There is valid concerns raised about the harvesting of sphagnum peat moss from Canada as being sustainable or not. It takes peat moss bogs several hundred to a thousand years to mature, depending on the conditions, so it is hard to “sustainably” manage them.

Looking at the soil it was fine and fairly light with some perlite easily seen among the peat moss. It looks a bit chunky, but the feel wasn’t. It did seem to have a few larger chunks of material, but that shouldn’t matter in starting seeds.

Not a bad seed starting mix, and we would take this over several store brands we’ve seen.

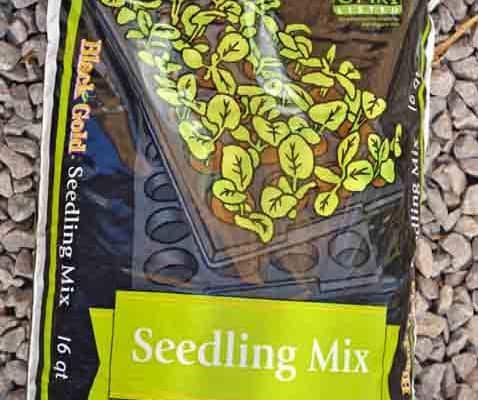

Black Gold Seedling Mix is another of the seed starting mixes listed by OMRI, and it says so on the top right side of the bag. Black Gold is a well known supplier for hydroponic growers and would be considered one of the premium or super-premium seed starting mixes.

We sourced this from True Value, so it should be available from an independent garden center but probably not from the big box stores. The bag has 16 quarts for $6.99, so is a good value with enough to start seedlings for a very large garden or for sharing between a couple of neighbors or a community garden. Black Gold’s online listing.

In addition to the OMRI listing, the label shows this seed starting mix to be enriched with silicon for thicker stems and improved root mass. While it is true that silica and silicon are important components to strong cell, stem and root growth, there is no mention of the silica in the ingredients. This might be a marketing approach, or it could be something worthwhile, but the bag doesn’t expand on the benefits.

Black Gold’s ingredients are pretty standard for seed starting mixes; peat moss, perlite, dolomite lime and Yucca extract as the organic wetting agent. Dolomite lime is calcium magnesium carbonate and increases the pH of soil, but also aids in organic decomposition. It is high in magnesium and calcium, which could be good for acidic soils but could be trouble for alkaline soils like we have in the West. The amount of dolomite lime is probably small and wouldn’t cause much of an effect in the amounts used in seed starting mixes, but might not be the best use as a garden or container amendment.

It is good to see what is used as the wetting agent – Yucca extract.

The appearance confirms what we would expect to see from the ingredients – lots of white perlite specks on a very dark peat moss background. It is light and fluffy, allowing good root penetration and establishment.

Because this is OMRI listed, we would choose it over a non-OMRI listed seed starting mix.

The final comparison is included even though it is labeled as a potting soil and isn’t one of the seed starting mixes. Garden Time’s Square Foot Gardening Potting Soil is about as close as you can come to a complete garden soil in a bag, and we’ve used it for a number of years to start seeds, transplant seedlings into and have been quite happy with the results.

The “Natural & Organic” label is prominent on the bag, even though this is not OMRI listed. Some of the other claims are “Proven Formula for Optimum Growth” and “Great for Vegetables”.

We sourced this from Lowe’s and have bought it at Home Depot in years past. We also saw it with a different bag in True Value. The company name is Garden Time and is a part of Gro-Well brands in Tempe, AZ. The bag is 1.3 cubic feet, which translates to 38.9 quarts for $8.98, making it by far the most cost effective seed starting medium. Garden Time’s Square Foot Gardening online listing.

The ingredients are compost, peat moss, coconut coir, vermiculite, bloodmeal, bone meal, kelp meal, cottonseed meal, alfalfa meal and worm castings. The peat moss, coir and vermiculite are classic seed starting mix ingredients, with the compost, different meals and worm castings adding nutrients to the soil for the plants growth and health. We use this as both a seed starting mix and potting soil or transplant soil because of the nutrients, which are lacking in straight seed starting mixes.

Looking at the mix it’s easy to see the vermiculite granules, which are gold colored specks instead of the white of perlite. It has a lot darker look due to the compost and additional nutrients.

Vermiculite is mica expanded by intense heat and is used much like perlite to retain water, decrease soil compaction and improve water retention.

Here’s the closeup look.

The breakdown of the costs per quart tell a story – they are in the ballpark of each other, with the exception of our rogue potting soil thrown in. Most of them have similar ingredients, with a few different additions.

If we had to buy a dedicated seed starting mix and couldn’t use the potting soil we do, our choice would be one that lists the ingredients and is OMRI listed. Having said that, any of the seed starting mixes with the primary ingredients of coconut coir (our preference) or peat moss with perlite or vermiculite would make a satisfactory seed starting mix.

What you choose will depend largely on the availability for you, how much you need and the cost.

As part of the test, we are starting seeds in all four mixes and have documented our results in Seed Germination Observations. Our Potting Soils article gives you some details on what to look for in good soils to transplant your young, tender seedlings into.

Aphids and Nitrogen

Aphids are one of the perennial pests that gardeners deal with, often with very mixed results. What works one year seems to fall flat on its face the next, with the reverse also being true. Aphids are tiny, soft bodied insects that have piercing, sucking mouthparts to feed on plant saps. They live in colonies, most often the underside of leaves and where the tender young growth is on a plant.

By themselves, aphids rarely outright kill a plant but they can inflict serious damage to both its flowers and fruit. It only takes a few aphids sucking on a young flower or fruit to weaken it or damage it beyond being edible. The sap they extract weakens the plant, stunting its growth and food production. The aphids can also be carriers or vectors of diseases or viruses, which they infect the plant with as they pierce the cell walls and extract the plant sap. Just a few seconds is all it takes for a virus to transfer from the mouth of an aphid to the plant.

Aphids will often arrive in a garden or on a plant by flying in. A small number will arrive and leave their wingless young who feed on the plant and immediately lay eggs, increasing the population quickly. The adults will then fly off and repeat this several times. This is why gardeners will often complain that the aphids overwhelmed the garden “overnight”. Each adult aphid can produce up to 80 offspring every week!

So what can be done about these insects? There are several methods of dealing with them, broken down into two main approaches – prevention and treatment. The prevention phase happens in the fall and early winter with soil testing and amendments that set the stage for success the next growing season. Treatment is just that – what to do when those pesky insects show up uninvited in your garden!

Aphids Love Nitrogen

Let’s start at the beginning, shall we? Nitrogen is a big, big player in the aphid dance. Aphids love nitrogen, plain and simple. They are attracted to the soft growing parts of a plant that are high in nitrogen, as it is a major factor in plant growth. Aphids are also really attracted to young seedlings, since everything on a seedling is growing and there is lots of nitrogen to be had.

Nitrogen plays a very important part in a plants growth as well as the content of its sap. Soils with excessively high nitrogen create very fast growing plants. This leads to rapid cell wall growth, which are elongated, thinner and much easier for the piercing mouth-parts of an aphid to penetrate than normal. The plant sap will also be high in nitrogen and will be especially attractive for the aphid. It is very important to understand that high nitrogen sap will be lower in overall sugar content – also known as brix – because nitrogen forms amino acids and proteins – such as chlorophyll – but specifically needs magnesium, phosphorus and carbon to form sugars. This can’t happen if there is excess nitrogen, as there aren’t enough of the other elements to form those sugars. Once the soil is amended with the correct nutrients, the plant will increase the brix/sugar levels and the aphids will die from sucking high sugar content plant sap as it is deadly – aphids can’t digest the sugars with no pancreas and thus die.

What all this means is that using high doses of chemical fertilizers will encourage aphids to call your garden home! Almost all commercial fertilizers are high in nitrogen and release their nutrients much faster than compost or other soil amendments, making aphid pressures much worse than they would normally be. They also contribute to lots of flowers with little fruit production or stunted and smaller than normal sized fruit.

It is interesting to note with soybean studies at Penn State University naturally occurring nitrogen-fixing bacteria – called rhizobia – provided a better form of naturally occurring nitrogen than the laboratory bred inoculated strains did. Plants growing in the naturally occurring rhizobia soils had markedly fewer aphids and stress than the inoculated ones. The amount of nitrogen provided by the lab developed rhizobia and the naturally occurring strains were the same, with the natural rhizobia having much lower aphid populations on the plants. They are continuing the study to see why this happens.

There is a concept at work here that we need to briefly discuss so that you can understand where we are going from here. The “Law of the Minimum” shows how interrelated many nutrients and elements are to healthy plants, not just the N,P and K that are listed on fertilizer bags.

The Law of the Minimum states,

“Plant growth is determined by the scarcest, “limiting” nutrient; if even one of the many required nutrients is deficient, the plant will not grow and produce at its optimum.”

Prevention and Preparation

The preventative method is to have a complete, comprehensive soil analysis done by a professional lab. I’ve mentioned these before, but they bear another – Crop Services International and Texas Plant and Soil Lab are great labs. They are thorough, friendly and will give you the info you need at a reasonable price. From this analysis, you will know exactly what soil nutrients, amendments and trace minerals are needed to eliminate a high nitrogen condition in your soil and plants, and by extension reducing the population and attraction of aphids.

Another, very simple method is to stop using commercially available chemical fertilizers! Without naming names, these come in a bag and sometimes have the word “miracle” attached to them. There are a number of brands that can be bought at any garden center or big box store in their garden section. Well-aged and decomposed compost – especially if you’ve worked with it how we discuss in our articles on compost – will give you a continuous supply of “soil food” to apply to your garden twice a year, in the early spring and again in the late fall. This compost with the amendments will slowly release the nutrients that the garden needs, along with attracting the biological elements in the soil that do the real work – earthworms, pillbugs, beneficial nematodes, fungi and all sorts of other hard-working critters that seriously improve the soil on a continuous basis.

Another aspect of prevention is cultural control, or removing the suitable environments where aphids can overwinter or establish an initial population to then swarm your garden. Standing weeds can be harbors of aphids, so remove them and remove dead plants from the garden in the fall. Don’t wait until the springtime to clean up the garden, as this can provide the perfect habitat for aphid eggs to be sheltered under. Inspect trees and bushes for aphid eggs in the fall, remove them by hand, vacuum or with a strong blast of water.

Treatment Options

Now that you’ve got the prevention and preparation covered, what can be done if and when the nasty aphids arrive? This is where the treatment portion comes in, and it would be wise to prepare for this as well. Early detection is very important for successful treatment, as if the aphids get a toe-hold, it will be much more difficult to rid your plants of several sizable populations instead of just one or two small ones. The incoming flights of adult aphids are random, so consistent inspection is best. This is very easy, just flip over the top, youngest leaves of several plants and look for the clusters of small aphids on the underside. Look around bud areas as well. If you see any aphids, they will be in small clusters or colonies and can be easily dealt with at this stage. Crush them by hand or prune the leaves or buds to remove them. Once you see the first small populations, go back and be very thorough with the rest of your plants, taking the time to examine them well. Trust me on this, the time spent now will save you much heartache, back ache, time and frustration in the very near future!

Aphids will excrete “honeydew” – a sweet, sticky substance – and is sometimes fed on by ants. This isn’t always the case; but in your inspections look for travel pathways of ants up and down the plant where the aphid colonies are. Sometimes the ants will lead you to the aphids that you would have otherwise missed.

Anytime you see any aphids, it is a good practice to set out yellow sticky traps. Aphids are highly attracted to the color yellow, which lures these little monsters into the traps. They are available at most garden centers and will be in squares or strips. Place several of them in the area where you find the aphids, and put out a few more than you might think. They are good inexpensive insurance.

If the aphids have colonized more than about 5% of the bud and young leaves of a plant, or are on more than that amount of your total garden plants, then it’s time for the next round of action.

Beyond physically removing the aphids, there are two approaches to treatment – biological and chemical controls. Biological controls use biology – predatory insects – to eat and control the aphids. Chemical controls are just what they sound like – using sprays of varying toxicity to reduce the aphids’ population.

Using the biological approach first combined with a non-toxic soapy spray is often the knockout punch needed for smaller aphid infestations. Releasing parasitic wasps that lay their eggs inside the aphids, ladybugs, lacewings, soldier beetles and the syrphid fly larvae are all highly effective if done in time, before the aphids’ population explodes. One of the best resources for biological controls is Arbico Organics. They will help you decide what species will work best for your garden situation, how many to release and how many times. Keep in mind that the goal is not to completely eliminate every single aphid, as then the beneficial and predatory insects won’t have a food source. The goal is to keep the aphids controlled, where they aren’t damaging the plants.

Remember, weather can be on your side when dealing with aphids. Heat and high humidity can really knock them back as they are fairly fragile and die off in droves when temperatures are over 90°F.

Soap sprays work by smothering the aphids by coating their skins. Start with a completely harmless soapy water spray like Dr. Bronner’s – using a tablespoon per half gallon in a hand sprayer. Make sure to apply the spray when beneficial insects aren’t around, as they will also be affected. From there, work up to an insecticidal soap like Safer Brand or horticultural oil such as neem oil. With both of these approaches, make sure to cover the underside of the infested leaves well for the smothering effect to work. These are contact controls, and depend on contact with the aphids to work, so they will need to be re-applied as often as needed until you’ve gotten control of the situation. This could mean once a day for a few days, then twice a week for a week or so, then tapering down to once a week. It might well take 2 – 3 weeks to really get a handle on persistent outbreaks, so be patient but persistent!

Moving up the toxicity ladder, multi part sprays such as our Home Garden Bug Solution work very well, but need to be used carefully as they do have a high level of insect toxicity even though they are made with no petrochemical ingredients. If you do need to bring out these big guns, test in a small area to see the effects before spraying your entire garden!

Hopefully you now see that there are a number of ways to reduce and control the pesky aphids in your garden. It all starts with prevention and preparation with improving the soil and balancing the nutrients it needs. From there you now have several new tools in your “pest control” toolbox to help you manage aphids in your garden next growing season.

Blossom end rot affects mainly tomatoes and peppers, but can affect other fruiting crops such as eggplant, watermelon and summer squash. This is a perennial problem, meaning that as a gardener, you will deal with this yearly in your garden. There are two approaches to working with blossom end rot – prevention and reaction, or a primary and secondary solution. Unfortunately, most gardeners only realize they have a problem when the fruit are showing black spots on the end. This is the acute phase – once there are problems – and immediate action is needed to prevent further damage to fruit that is just beginning to set.

We will look at the underlying causes of blossom end rot, along with what happens and what can be done about it in the prevention as well as the acute phase.

As mentioned, blossom end rot will affect more than just tomatoes and peppers, but we will focus mainly on those as this is what most gardeners’ experience. Just tuck the other varieties into the back of your mind, and you’ll have a jump start if you see it strike them. In reality, the prevention will most likely have a beneficial effect for everything as you will be creating an environment that won’t support the cause of the problem!

Blossom end rot is caused by a lack of enough available calcium in the fruit at the blossom end. What most often alerts us is a black spot or patch at the blossom end of the tomato or chile, opposite of the stem. This black spot is a secondary issue caused by a fungus attacking the weakened fruit. Contrary to what many think, we aren’t aiming for the eradication of the fungus and resulting black patch, but fixing and preventing the cause of the problem. Correcting the underlying issues that lead to the weakened fruit will automatically prevent the fungus from being able to attack.

Let’s start with the problem and work backwards, to better understand what is needed for both an acute fix and a preventative approach for blossom end rot. Calcium is a very important part of the growth process for plants and the proper development of high quality, tasty fruit as it contributes to healthy cell wall growth, insect resistance and helps to regulate many cell processes. Calcium is non-mobile in the plant once it is imported, meaning the plant can’t move it from one part of itself into the fruit, or from one part of the fruit to another. Thus, the tomato or chile plant needs a continuous supply of calcium as it grows, flowers and produce fruit all through the season.

Blossom end rot usually occurs early in the season with the first or second flush of fruit. It happens just when the plant is at maximum growth and is putting on the first fruit, with a second set of flowers on the way. It is in high gear and needs all of its nutrients available to be healthy, resist pests and disease, as well as grow lots of delicious tomatoes and peppers. The key to preventing blossom end rot is to supply a sufficient, steady amount of calcium to the plant so it can be transported into the fruit continuously. Problem solved!

Not so fast, just how can we make sure that the plant has a steady supply of calcium?

Here is where we branch off into the two approaches – the primary and the secondary. The primary, preventative approach is to have enough calcium in the soil that feeds the roots and is transported to the fruit throughout the growing season. That calcium in the soil must be ‘available’ meaning that the roots can actually absorb it and transport it where it is needed. Available means that it isn’t tied up by another mineral or a pH level that won’t ‘let go’ of it. There is more to the story than just adding a calcium amendment to the garden bed!

A very good example of this is where we live in central AZ, there is a decent amount of calcium in the soil that plates out on faucets and glassware as a calcium deposit. Conventional wisdom says not to worry about calcium because it is everywhere. That’s true, but the challenge we have is the pH of the soil is fairly alkaline at 8+ on the pH scale, so the calcium is ‘tied up’, or not available to the plants. This is proven by the weed populations we typically see that only grow in calcium deficient soils.

So what can be done? A comprehensive soil test is one of the best, first steps to take. This is much more than the simple NPK type of test done by university extension offices or the do-it-yourself test kits bought at the local garden center. A complete soil analysis is one that is collected and sent off to a recognized, professional lab that sends back a report on every mineral found along with recommendations on what direction to go and what nutrients to add in what form. They will usually cost from $25 to $75 range, depending on what analysis and information you need. There are several of these labs in the US; the two that we’ve worked with and are familiar with are Crop Services International and Texas Plant and Soil Lab. From this, you will have a very good indication of where to go next.

Fall is a great time to get your soil tested and amended in preparation for next spring’s season for a few reasons – the soil testing labs are generally not as busy, so results are quicker; and soil amendments will need some time to become integrated and available into the soil nutrients, so fall gives you the needed time, and it is easily incorporated into the traditional fall garden cleanup and prep.

Calcium is closely tied with magnesium, and this will be indicated on the soil analysis. More acidic soils, such as those generally found in the eastern states, will benefit from lime or calcium carbonate, while the more alkaline soils in the western states will need gypsum or calcium sulfate. Lime tends to raise the pH, while gypsum tends to lower it.

Water plays an often overlooked, but equally important, role in the blossom end rot saga. Inconsistent levels and rates of water will greatly vary the amount of calcium and other nutrients available to the plant, increasing the chance of diseases attacking the fruit like blossom end rot. This is one of the reasons we talk a lot about a drip system on a timer – it really helps even out the moisture levels in the soil and greatly reduces the stress on the entire garden, with the happy result of lowered amounts of nutrient and stress related problems. Of course, the weather can also play havoc with all of our carefully laid plans, as heavy and sudden rainfall can cause blossom end rot and splitting of tomatoes, along with a noticeable ‘wash-out’ of flavor and taste.

This is where the acute or secondary approach is needed. Calcium carbonate tablets, or anti-acid tablets (Tums or the equivalent) work great when a couple of them are inserted at the base of a tomato or chile plant, where they will dissolve and make the calcium available to the plant in just a few hours, saving this flush of fruit if done right after the rains, or the next set if done when blossom end rot is first noticed.

Another approach is to feed calcium directly to the roots through the drip system as a liquid fertilizer, usually with calcium chloride or calcium nitrate. This approach works very well in offsetting one of the most overlooked causes of blossom end rot – great weather. That’s right – excellent weather with moderate temperatures and lots of sunshine put the plants into overdrive, and their rapid growth can often simply outstrip the amount of available calcium in the soil, even if you have been proactive last fall. The calcium just cannot be taken up out of the soil fast enough, so feeding through the drip system can be a big bonus during these times. The secondary approach will always be needed, even if you’ve done your homework and amended the soil the previous fall.

Calcium isn’t absorbed very well by the leaves of a plant, especially older leaves. The roots are much better at absorption, plus they can transport the calcium faster than through a foliar approach. For these reasons, stay away from trying a foliar spray to supply calcium to your tomatoes.

Blossom end rot won’t ever quite go away, because of the reasons you’ve seen here. With some knowledge and practice, you can easily create a much better environment in the soil that supports the plants much more fully and then use the supplemental approach to keeping the calcium levels high enough to minimize blossom end rot and keep more of your hard work for your dining table instead of as scraps for the chickens or compost pile!

Fish Emulsion Feeds Your Plants

Fish emulsion has been a go-to product for the organic and natural home gardener for years now, as it has proven its effectiveness in feeding the soil and plants with biologically available nutrients while increasing soil and microbe health. The main drawback to commercial fish emulsion is the cost and the smell. While we can’t do anything to help you with the fishy smell, we can help you make your own fish emulsion that will not only save you a lot of money in product and shipping costs, but just might make a better product than you can buy! This homemade fish emulsion will almost always supply more nutrients than commercially available, but also supplies much more beneficial bacteria from the brewing process. In order to ship, commercial emulsions have little to no active bacteria, because they make containers swell as they continue to grow!

All fish emulsions are good organic nitrogen sources, but they also supply phosphorus, potassium, amino acids, proteins and trace elements or micro-nutrients that are really needed to provide deep nutrition to your soil community and plants. One of the benefits of fish emulsion is that they provide a slower release of nutrients into the soil without over-feeding all at once. It is usually applied as a soil drench, but some gardeners swear by using it as a foliar fertilizer as well.

Adding seaweed or kelp to the brewing process adds about 60 trace elements and natural growth hormones to the mix, really boosting the effectiveness of the fish emulsion. The seaweed or kelp transforms the emulsion into a complete biological fertilizer. Beneficial soil fungi love seaweed. Dried seaweed is available at most oriental grocery stores. The amount you need to add will depend entirely on your soil needs. If you are just getting started in improving your soil, add up to a cup of dried seaweed or 2 – 3 cups fresh. If your soil is doing pretty good then add about 1/4 to 1/2 cup of dried seaweed and up to 1 – 2 cups fresh.

Making Your Own Fish Emulsion

To make your own, obtain a dedicated 5 gallon bucket for this project. Trust me; you won’t want to use it for anything else once you’re done! Buy 10 cans of herring type fish such as sardines, mackerel or anchovies. Sourcing these from a dollar store or scratch and dent store makes perfect sense, as you don’t care about the can and aren’t going to eat them.

Rich, well-aged compost is a key ingredient to great fish emulsion, as it has lots of active microbes and other biological life which will help kick-start the fermentation of the fish. A good compost hunting dog is not required, but really helps. We’ve found the Doberman breed to be very helpful in finding just the right compost! Dalmatians do a pretty good job as well.

Fill the bucket half full of well-aged compost, aged sawdust or leaves, or a combination of all three. You are looking for the dark brown, crumbly compost that smells like rich earth.

Add water to about 2 inches from the top…

add in the cans of fish, rinsing the cans with the water to make sure you get every last drop of the “good stuff”. The juices or oils in the can will breed beneficial microbes and supply extra proteins.

To supercharge the brew, add 1/4 to 1/2 cup of blackstrap molasses to provide sugars and minerals to the fermenting process. The sugars also help control odors. Next, add the chopped or powdered seaweed to the mix. If you need extra sulfur and magnesium, add 1 Tbs Epsom salts.

Stir well and cover with a lid to control the odor, but not tightly as it will build pressure as it brews.

Be Careful!

NOTE – Make sure that flies do not get into the bucket or you will have a marvelous breeding ground for maggots! One solution is to drill several holes in the lid for the bucket and glue screen mesh on the inside of the lid, allowing air flow but keeping those pesky flies out. Remember, you are brewing the most delicious aromas the flies have ever smelled!

Let it Ferment

Let it brew for at least 2 weeks, a month is better. Give the contents a good stir every couple of days.

Once it has brewed for a month, it is ready for use!

There are a lot of ways to use this brew, so be creative. Some folks will strain off the solids, put them in the compost pile and use the liquid as a concentrated “tea” to be diluted with water. Others keep everything together and stir the mix well before taking what they need. What you have is a supply of bio-available nutrients in a soluble form.

Use as a Soil Drench and Foliar Fertilizer

For a soil drench, use 2 – 3 Tbs per gallon of water and apply to the roots on a monthly basis during the growing season. 1 Tbs per gallon of water makes a good foliar fertilizer. Just make sure to apply it by misting during the cooler parts of the day, not drenching the leaves in the heat. Half a cup per gallon will give your compost pile a kick start.

This brew will keep for at least a year, but you might want to make fresh each season. If you need less than 5 gallons, halve or quarter the recipe. It will smell, so store it where the odor won’t knock you out. I don’t trust the “deodorized” fish emulsions, as to remove the odor, some component of the fish product was removed either physically or chemically and is no longer available as a nutrient.

Fresh Coffee Grounds Are Great Source of Minerals and Nutrients

Looking to perk up your compost pile? Do you drink coffee? You might be holding the answer in your hands this very moment, or at least part of the answer. Coffee grounds have been used for many years by those “in the know” to boost the quality of their compost, making a superior soil amendment for free. The grounds are considered part of the “green” portion of the composting, speeding up the decomposition process while keeping temperatures high enough to kill off pathogens.

Coffee grounds provide energy in the form of nitrogen to the hard working bacteria doing all of the work in the compost. They also encourage beneficial microbe growth, contributing to a healthier soil. Another benefit is the minerals added to the compost such as phosphorus, potassium, magnesium and copper – all very necessary to the growing process. Earthworms absolutely love coffee grounds, preferring them to other food sources and turning them into highly prized vermicompost. For many years coffee grounds have been thought of as slightly acidic, but recent research shows that the grounds are usually pretty neutral in pH, but have a very high buffering capacity. This means that whether the soil is acidic or alkaline, the grounds will bring the pH back toward neutral, so they are good for any soil types. The moisture holding ability is very beneficial for loose soils, yet it acts to loosen heavy clay soils at the same time.

Some gardeners have worked the grounds directly into the soil, but it is best to add them to the compost pile and let decomposition release their nutrients first, then add the aged compost to the garden soil, working it into the top 2 – 3 inches in early spring and late fall. The grounds can make up to 25% by volume of the compost, and be used as a manure replacement for gardeners who don’t have ready access to those sources. Some city gardeners make their compost of leaves, cardboard and newspapers for the carbon side with coffee grounds and fresh grass clippings supplying the nitrogen to keep the pile going. It is best to let the compost decompose or age for at least 6 months, with a year time-frame yielding a higher quality amendment that looks very much like soil all by itself.

“Can raw milk make grass grow? More specifically, can one application of three gallons of raw milk on an acre of land produce a large amount of grass?”

David Wetzel is the person possibly most responsible for bringing the ancient practice of applying milk to the soil in order to improve the health, disease resistance, and productivity of the soil. As part of a 10-year study in collaboration with the University of Nebraska soil specialists and weed specialists as well as insect specialists have proven the effectiveness of milk as a soil improver.

It started with David having excess skim milk that he didn’t want to waste, so he started applying it to a pasture on his farm and noticed several oddities about that particular pasture. When his dairy herd was turned out on it, the butterfat content of the milk increased by 3-4% within 2-3 days of being in that pasture, every time. Not only that, but the herd needed fewer vet visits, maintained their weight better and the pasture recovered faster and produced more hay than other pastures. David contacted his next-door neighbor, Terry Gompert, an extension agent for the University of Nebraska about the phenomenon, and a multiple-year study was born. One of the additional benefits of spraying the milk has been a drastic reduction in grasshopper populations in the pastures, as the milk sugars are toxic to soft-bodied insects. One theory is that grasshoppers will leave healthy plants alone, as the milk feeds the plant as well as the soil.

The following article is from Ralph Voss, a student of David’s methods, followed by David’s own observations on what is working on his farm.

Mon, 2010-03-08

“This article appeared in the March 10, 2010, issue of theUnterrified Democrat, a weekly newspaper published in Linn, Mo., since 1866. In addition to writing for the paper, Voss raises registered South Poll cattle on pathetically poor grass that he is trying desperately to improve.”

Nebraska dairyman applies raw milk to pastures and watches the grass grow

An Illinois steel-company executive turned Nebraska dairyman has stumbled onto an amazingly low-cost way to grow high-quality grass – and probably even crops – on depleted soil.

Can raw milk make grass grow? More specifically, can one application of three gallons of raw milk on an acre of land produce a large amount of grass?

The answer to both questions is yes.

Call it the Nebraska Plan or call it the raw milk strategy or call it downright amazing, but the fact is Nebraska dairyman David Wetzel is producing high-quality grass by applying raw milk to his fields and a Nebraska Extension agent has confirmed the dairyman’s accomplishments.

David Wetzel is not your ordinary dairyman, nor is Terry Gompert your ordinary Extension agent. Ten years ago Wetzel was winding up a five-year stint as the vice president of an Illinois steel company and felt the need to get out of the corporate rat race. At first he and his wife thought they would purchase a resort, but he then decided on a farm because he liked to work with his hands. The Wetzels bought a 320 acre farm in Page, Neb., in the northeast part of the state, and moved to the farm on New Year’s Day in 2000.

“We had to figure out what to do with the farm,” Wetzel said, “so we took a class from Terry Gompert.” They were advised to start a grass-based dairy and that’s what they did. “There’s no money in farming unless you’re huge,” Wetzel said, or unless the farmer develops specialty products, which is what they did.

In their business, the Wetzels used the fats in the milk and the skim milk was a waste product. “We had a lot of extra skim milk and we started dumping it on our fields,” Wetzel said. “At first we had a tank and drove it up and down the fields with the spout open. Later we borrowed a neighbor’s sprayer.”

Sometime in the winter of 2002 they had arranged to have some soil samples taken by a fertilizer company and on the day company employees arrived to do the sampling, it was 15 below zero. To their astonishment they discovered the probe went right into the soil in the fields where raw milk had been applied. In other fields the probe would not penetrate at all.

“I didn’t realize what we had,” Wetzel said. “I had an inkling something was going on and I thought it was probably the right thing to do.” For a number of years he continued to apply the milk the same way he had been doing, but in recent years he has had a local fertilizer company spray a mixture that includes liquid molasses and liquid fish, as well as raw milk. In addition he spreads 100 to 200 pounds of lime each year.

Gompert, the extension agent that suggested Wetzel start a grass-based dairy, had always been nearby – literally. The two are neighbors and talk frequently. It was in 2005 that Gompert, with the help of university soils specialist Charles Shapiro and weed specialist Stevan Kenzevic, conducted a test to determine the effectiveness of what Wetzel had been doing.

That the raw milk had a big impact on the pasture was never in doubt, according to Gompert. “You could see by both the color and the volume of the grass that there was a big increase in production.” In the test the raw milk was sprayed on at four different rates – 3, 5, 10 and 20 gallons per acre – on four separate tracts of land. At the 3-gallon rate 17 gallons of water were mixed with the milk, while the 20-gallon rate was straight milk. Surprisingly the test showed no difference between the 3-, 5-, 10- and 20-gallon rates.

The test began with the spraying of the milk in mid-May, with mid-April being a reasonable target date here in central Missouri. Forty-five days later the 16 plots were clipped and an extra 1200 pounds of grass on a dry matter basis were shown to have been grown on the treated versus non-treated land. That’s phenomenal, but possibly even more amazing is the fact the porosity of the soil – that is, the ability to absorb water and air – was found to have doubled.

So what’s going on? Gompert and Wetzel are both convinced what we have here is microbial action. “When raw milk is applied to land that has been abused, it feeds what is left of the microbes, plus it introduces microbes to the soil,” Wetzel explained, adding that “In my calculations it is much more profitable (to put milk on his pastures) than to sell to any co-op for the price they are paying.”

Wetzel’s Observations

Wetzel has been applying raw milk to his fields for 10 years, and during that time has made the following observations:

* Raw milk can be sprayed on the ground or the grass; either will work.

* Spraying milk on land causes grasshoppers to disappear. The theory is that insects do not bother healthy plants,which are defined by how much sugar is in the plants. Insects (including grasshoppers) do not have a pancreas so they cannot process sugar. Milk is a wonderful source of sugar and the grasshoppers cannot handle the sugar. They die or leave as fast as their little hoppers can take them.

* Theory why milk works. The air is 78% nitrogen. God did not put this in the air for us but rather the plants. Raw milk feeds microbes/bugs in the soil. What do microbes need for growth? Protein, sugar, water, heat. Raw milk has one of the most complete amino acid (protein) structures known in a food. Raw milk has one of the best sugar complexes known in a food, including the natural enzyme structure to utilize these sugars. For explosive microbe growth the microbes utilize vitamin B and enzymes. What do you give a cow when the cow’s rumen is not functioning on all cylinders (the microbes are not working)? Many will give a vitamin B shot (natural farmers will give a mouthful of raw milk yogurt). Vitamin B is a super duper microbe stimulant. There is not a food that is more potent in the complete vitamin B complex than raw milk (this complex is destroyed with pasteurization). Raw milk is one of the best sources for enzymes, which break down food into more usable forms for both plants and microbes. (Again, pasteurization destroys enzyme systems.)

* Sodium in the soilis reduced by half. I assume this reflects damage from chemicals is broken down/cleaned up by the microbes and or enzymes.

* If you choose to buy raw milk from a neighbor to spread on your land, consider offering the farmer double or triple what he is paid to sell to the local dairy plant. Reward the dairy farmer as this will start a conversation and stir the pot. The cost for the milk, even at double or triple the price of conventional marketing, is still a very cheap soil enhancer.

* Encourage all to use their imagination to grow the potential applications of raw milk in agriculture, horticulture andthe like – even industrial uses –possibly waste water treatment.