We can move beyond being a mere acquaintance to become a true friend to the sunflower, if we simply take the time to listen.

Tag Archive for: Philosophy

Learn about the true value of a home garden in enhancing well-being and providing a soothing escape from daily challenges.

Uncover the power of a systems approach for gardens. Understand the interconnectedness of plants, insects, soil, and more for a thriving ecosystem.

We want to share GrowHaus with you. During recent travels, we toured this amazing micro-farm in the northeast section of Denver, CO. Starting with an old flower greenhouse in an isolated immigrant neighborhood, this is now a model of innovative urban farming.

Healthy Food is a Right, not a Privilege

GrowHaus is a non-profit indoor farm, marketplace and educational center in north Denver, CO. The neighborhood of Elyria-Swansea is a historically working class immigrant community. It is surrounded by industrial manufacturing and transportation industries. As a result the neighborhood is listed as the most polluted ZIP code in Colorado.

The Elyria-Swansea neighborhood has been a first home for recent immigrants since the 1880s. It has always had one of the lowest household incomes in the city with low education and employment levels.

The area has endured a lack of access to healthy and affordable food with high rates of diet-related illnesses. This is due to their isolation within the industrial manufacturing and heavy industry areas.

Their motto is “Healthy food is a right, not a privilege.”

GrowHaus developed out of an old flower greenhouse. It incorporates several methods of growing food for local residents and restaurants in Denver.

We saw this is still a very busy industrial area with a large roofing and asphalt company and 4 lines of railroad tracks across the street.

The large hand-painted “Mercado” sign above a roll-up garage door indicated something unusual. The sign shows that vegetables, fruit, meat, dairy and more are available inside. Spanish and English are the predominant languages spoken here now, but historically this area has been a settling place for many different nationalities.

Challenging Conditions

The map shows just how crowded things are. A major rail line with multiple tracks is less than 50 feet from the front door. A large roofing and asphalt company are across the street to the east.

The modest sized homes are clear, with the line of older single wide mobile homes just to the right in the photo.

Just outside of the photo to the bottom is I-70, with its update and expansion just beginning. Much of the neighborhood to the south of the GrowHaus will be lost to the expansion and re-alignment.

When completed, I-70 will come within a couple hundred feet of the greenhouse. Two new light rail lines will be built in the next 10 years, cutting through the neighborhood.

Click to expand the close-up photo of the greenhouse and see just how tightly packed in the GrowHaus is.

The amount of food, education and community improvement that happens in this space is nothing short of amazing!

Our tour guide was an employee who is also a local resident. His insights and comments were very beneficial, having grown up in the neighborhood.

The food grown in the greenhouse is a world better than the boxed and fast foods he grew up eating!

Serious Food Production in a Small Space

There is both a hydroponics and aquaponics operation in the greenhouse. By partnering with local residents to grow food, provide jobs and education, everyone lives better.

Residents gain a valuable skill while earning money growing food they share with their families.

The hydroponics operation is 5,000 square feet and grows leafy greens. The customers are residents and local markets and restaurants throughout Denver. They grow about 1,200 heads of leafy greens per week using 90% less water than conventional farming.

The aquaponics side is 3,200 square feet, growing more leafy greens.

A commercial mushroom farm produces fresh specialty mushrooms year round for local use, restaurants and markets.

There is also a seedling starting nursery that’s just getting started. The nursery provides seedlings and young plant starts to area gardeners.

GrowHaus is a vibrant and essential part of both the local and extended community in Denver.

Our tour guide explains the growing, marketing and distribution of the butter lettuce from the hydroponics farm. Local residents who qualify buy food at cost with a sliding scale for other customers.

A closer look at the butter lettuce and packaging. It is marketed as “living” lettuce because the roots are still attached. It stays fresher longer than conventionally grown lettuce that is cut from its roots when harvested.

This brings a premium price from restaurants and markets in Denver, increasing the earnings of the hydroponics farm.

Easing the Food Desert

The Elyria-Swansea neighborhood is classified as a “food desert”. This is defined as “an urban area in which it is difficult to buy affordable or good-quality fresh food.”

GrowHaus works to overcome this through three food distribution programs. They are food boxes, the GrowHaus market and Cosechando Salud, a free food pantry and cooking class.

Food boxes are like a traditional CSA with food from GrowHaus and partner organizations. They have fresh fruits, vegetables and other items. The program is open to anyone in the greater Denver area.

The Mercado de al Lado is the neighborhood market, offering fresh produce, meat and dairy products year round.

The pricing is unique, using a tiered pricing system so that everyone has the maximum access to the healthiest foods possible.

Those that qualify can buy food at cost or a small percentage above the production cost. This gives greater access to healthy and fresh food to those who really need it.

Those who can afford to pay slightly below retail up to full retail prices, bringing profits to the program and keeping it running.

The Cosechando Salud is a free food pantry and cooking class. It is supported by the profits of the distribution programs. It teaches cooking essentials while providing healthy food that was not sold at the markets, avoiding excess food waste.

Permaculture and Classroom Space

The class space and common area are a permaculture design. It is a self-regulating edible ecosystem with figs, bananas and papayas. There are composting systems with worms, along with rabbits and chickens.

Growing bananas and papayas at a mile high in Denver’s climate is pretty impressive!

People Making a Difference

It is inspiring seeing the scope of the operations at GrowHaus, along with the number of programs and organizations they partner with.

A small group of dedicated individuals have accomplished much with a challenging environment in an isolated neighborhood.

They have created a working, local, sustainable healthy food system which lives up to its mission. In doing so, they have also created a model of how inclusive participation and open cooperation with other like-minded organizations can expand the positive impact.

We left with the realization that one person can make a difference, even if it is in one other person’s life. That difference, and the results, are worth it!

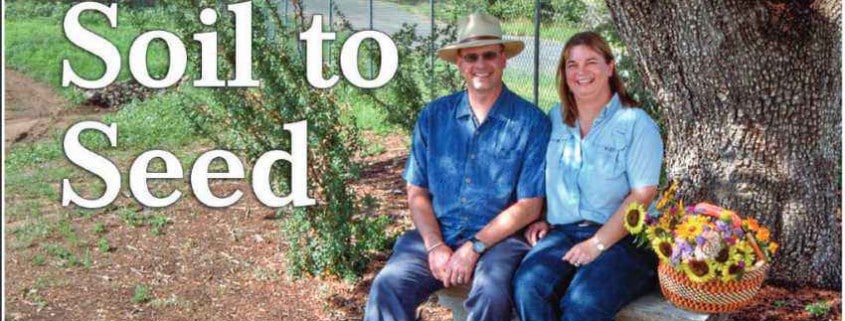

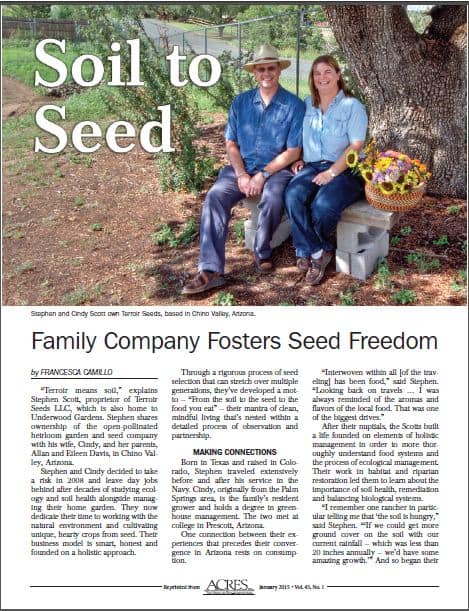

Family Company Fosters Seed Freedom

Want to learn more about what makes Terroir Seeds different? We are excited to be featured in the January 2015 issue of Acres USA magazine, the voice of eco-agriculture for over 40 years. This will give you great insight into what makes Terroir Seeds so unique in today’s seed world.

These varieties are featured in the article – Zapotec Tomato, Chile de Agua, Kentucky Wonder Pole Bean, and Rosemary.

Click the photo to read the article!

Food is something that many of us in the US, quite literally, take for granted. We have reached the point where we simply don’t think about it much anymore. This has become both a blessing and a curse.

For most of us, food is always available, never in short supply and the choices can be staggering. Do we want Asian, Italian, Mexican or American tonight? Easy enough. For some, we can drill down much deeper to regional cuisines of the world available for the price of a phone call or a short drive. The selection at the supermarket or grocery store has exploded, with even the most mundane supermarket in small towns offering aisles of international food that have never been seen before in history.

Of course, any discussion of food is by definition a complex one, and the acknowledgment must be made of the less fortunate that live in “food deserts” where the only available food within 30 minutes is at a convenience store; and those that are euphemistically classified as “food insecure” – meaning hungry. Yes, here in America where we are constantly being told that we must “feed the world” with industrial agriculture, we have a dirty little open secret – 1 in 7 or 49 million of our own people don’t have enough to eat, or don’t know where their next meal will come from.

Today we will look at a slightly different picture, that of food as it relates to civilization and how it can affect all of our lives in positive or negative ways. Food can support or topple governments, as vividly demonstrated by the fairly recent events of the “Arab Spring” uprising in the Middle East where food prices and availability brought down established governments in a matter of weeks.

Henry Kissinger’s famous quip from the 1970s rings as chillingly true today as it did then, “If you control the oil you control the country; if you control food, you control the population.”

In light of that, let’s look at some excerpts from Dr. Vandana Shiva’s lecture we attended at Arizona State University’s Global School of Sustainability on October 30, 2014. Her lecture was titled “Future of Food: Dictatorship or Democracy?” For those not familiar with Dr. Shiva, she is a physicist, environmental activist, speaker and author. Her newest book is Making Peace with the Earth.

Food is the web of life, with interactions between different organisms. The soil food web is such an amazing contradiction to that extremely false idea that life is a pyramid with man on top. The organisms in the soil are one step beyond us, we are their food. That should bring us a bit of humility!

How true this is! In our everyday lives, we often forget that we continue to be here thanks to about 6 inches of soil that feeds us multiple times a day, every week, all year long throughout our lifetimes. 2015 is designated as the International Year of Soils by the UN General Assembly, in recognition of the overlooked importance soil plays in all of our lives.

How we produce and consume food is probably the most significant impact both on the planet and society.

Food is more important in our daily lives than we probably realize on a regular basis. Not only does it feed and nourish us, it brings us together socially at mealtimes, holidays and festivities as well as having a major impact in our political system and our national policies, both at home and abroad. The Farm Bill and international trade agreements are just two examples of this importance.

When Dr. Shiva was doing research in the Punjab region of India for her 1992 book “The Violence of the Green Revolution”, she realized that

When you can’t choose what you grow, when you can’t decide the methods of production, when you don’t determine the price of what you produce, when your own rivers’ water can’t be released through your decision, then you are living under slavery.

When she said this, it immediately brought to mind the situations of some of our farmers, especially the contracted chicken and pig producers, as well as commodity crop growers who are locked into multi-year contracts that specify everything – the seed, chicks or piglets to be used, what feed or fertilizers, pesticides or herbicides will be applied, the length of time until harvest and what price will be paid by the buyer after harvest. There are often punitive clauses that penalize the grower or farmer if conditions or quotas aren’t met. Some large operations, corporations themselves, do well in these contracts, but family farmers do not often find them beneficial in the long run.

A dictatorship is control of an absolute kind. Look at what is happening to our food system – seed, the first link in the food system is being controlled like we’ve never seen before. It was not controlled before, it was shared. We had public universities breeding seed, and they would share the seed. Farmers would share seed with each other.

The issue of food dictatorship begins with the seed, goes into food, goes into our knowledge, goes into how our decisions are made, because governments become involved with the laws they make.

This is a very important point that is not addressed much in today’s food system discussions; the very beginning of the entire food chain comes down to a seed. We have seen the incredible consolidation of almost an entire industry in a little more than a decade. From dozens of companies, we now have 6 that control 80% of the commercial seed supply worldwide.

In decades past, land grant universities bred new open pollinated varieties and shared them with growers in their state. Those growers further selected for the best traits and passed them along, partly sharing and selling. The USDA had a large breeding and research section that would send seed home with Senators and Congressmen when they went back home on the train. Farmers and growers could subscribe to the USDA’s publication, read about new varieties they were interested in and write for samples of seed to try. Bear in mind, these weren’t “Free” seeds; they were paid for by taxes and funded through the agricultural programs of the USDA. The growers and farmers didn’t pay out of pocket for them, but paid via their taxes.

Now, there are very few public universities doing seed research and breeding that are releasing them to the public. The notable exception was in April of 2014 when the University of Wisconsin, Madison ‘Open Source Seed Initiative’ project released 29 new varieties of seed for 14 different crops. Because this type of program was so unknown, many articles and Facebook posts erroneously trumpeted the “Free Seed Initiative”, creating confusion as to what this breeding program was trying to do. The aim of this project is to get new open pollinated seed varieties into growers hands so that they can become available for the public.

This is what seed democracy and by extension, food democracy, looks like. This is what is happening with every small, independent heirloom seed company that works to bring overlooked heirloom seed varieties to market. It is also what is happening with the explosion of Farmer’s Markets across the US, as well as the sustained double-digit growth in the resurgence of the home based backyard garden. Local food hubs and food production systems are being re-thought, re-engineered and re-designed like never before. Farmers and growers who used to see themselves as ‘competitors’ are now beginning to view each other as ‘collaborators’ or ‘co-creators’ in new ventures, with an improved local food system as the result.

Seed sovereignty is the very basis of food sovereignty, of food democracy. Every UN study shows that small scale agroecology produces more food than industrial chemical agriculture. The United Nations Environmental Program 2012 study “Avoiding Future Famines” defends the ecological foundations of traditional, sustainable agriculture.

Something like 70% of the food we eat worldwide is still grown today by small farmers. This has been true for centuries in places like Russia with its ‘Dacha gardening’ system growing close to 50% of the fresh food by the people, for the people. Food democracy can exist, even under the strictest non-democratic governments!

The biotech companies produce seed that is very costly; it is only the governmental subsidies that produce food that is cheap. There is $400 billion in agricultural subsidies – a billion dollars a day!

If that tax money was diverted from subsidizing toxic food that’s destroying the planet and destroying our health and shifted to growing food that protects our health, protects the planet and generates employment in the process, then we could begin to reverse the agricultural damage to the world.

75% of planetary damage to soil, water and biodiversity and 40% of the greenhouse gases comes from global industrial agriculture. This is the single biggest impact on the planet, and yet ecological farming and local food systems can be the place, maybe, to do the opposite. We can rejuvenate biodiversity, we can save seed, we build up organic fertility of the soil, and we conserve water.

This is big-picture thinking, but on many scales it makes sense in many ways. Voluntary, participatory and evolutionary seed breeding projects that are not corporately involved can be very strong food security and food democracy measures today. In times of changing climactic conditions, the plants must be allowed and encouraged to adapt to the current agricultural conditions. Farmers have done this for centuries, evolving salt tolerant or arid varieties that continue to produce food during changing times.

A perfect example of this was after the 2004 Tsunami in Thailand and Indonesia. Dr. Shiva’s foundation, Navdanya, a participatory agricultural research program – gifted 2 truckloads of salt tolerant seeds to the farmers, who had been told that no agriculture was possible for 5 years by their government agricultural resources. The seeds didn’t just survive; they did extremely well and have been saved and shared all across the region. Seeds are hope, the hope for our future. They are the real diversity, the real insurance for the future, whether it is climate change, to create democracy or deal with pest and diseases.

What is your role in creating a food democracy instead of a food dictatorship? Do what you can – grow a garden or expand it, help others garden, grow a row for the hungry and donate it to your local food pantry, buy at the Farmer’s Market, buy a CSA share from a local grower, and choose the closest grown produce at the supermarket. Each of us individually may not be able to influence farm policy, but we can make a change in our daily food, and that is where real, lasting change starts.

Seed quality matters, whether you are a home gardener, small-scale grower or large farmer; whether you buy all of your seeds, save some for next season or a combination, this information can help you be better informed, make better choices and buy more wisely.

The marriage of the concepts of heirloom seeds and seed saving is not new by any means, but rather one that has been growing and gaining ground in the past several years. For some, this is a welcome return to a more traditional method of agriculture, while others use heirlooms for their flavor and diversity to improve the breadth of their products and offerings to the public.

Cindy and I have been home gardeners for 18 years and involved with soil restoration and rangeland improvement projects with local ranchers for 20 years. Our interest in food, especially good food, goes back a bit further than that! Our appreciation for seed quality and seed saving came from both our work with soils and interest and enjoyment of good food. Tasting the flavors of our garden produce sparked the interest of how to keep those characteristics that the seed produced for the future, to be able to enjoy them and share with others. Thus our seed saving education began.

Several years after taking over, refining and expanding an established family owned heirloom seed company of 20 years, we’ve gained knowledge from the differences and similarities in seed quality, production and seed saving from these two different perspectives. We want to share some of these with you; along with lessons we’ve learned along the way that can help improve everyone’s seed quality.

We will work from a point-to-point framework, showing the goals, concerns, differences, and similarities in both types of seed production and preservation approaches.

The foundational goal is the same for both the home gardener and seed company – having a sufficient quantity of high-quality seed stock of each variety needed for next year that is pure and true to type. This sounds simple enough, but in practice is not always easy to accomplish for either one.

We are approaching this from a seed quality standpoint, not just a seed saving one. Saving seed is fairly simple to do, but the results from planting those seeds can be very mixed; without a basis of understanding of seed quality, people can be disappointed and confused as to why they got the results they did. Both the home gardener and the seed company must understand seed quality to be successful in their respective endeavors.

Goals

Let’s look at the goals and concerns from both points of view:

The home gardener might state the reason for saving seeds as, “Enough seeds for next year’s planting, reduce the amount of seeds needed to buy, take advantage of selection and adaptation to achieve better production in our local climate.” These reasons are the very roots of why home scale seed production is important on a local and regional scale. A diversity of varieties are kept alive that are simply not possible on a national scale, as some regional adaptation can only happen in a small geographical area and won’t be applicable to a larger audience, but are no less important for the local people in that area.

As a seed company, our goals might be, “Produce a sufficient quantity of enough varieties and volume of seed to sell next season, introduce several new varieties, provide a wider selection for gardeners than they can produce themselves and provide a high-quality standard that maintains our reputation.” This reflects how the seed industry started, by offering varieties that were new, unusual or were not available in an area and offering a professional standard of germination and production that benefitted the gardener and grower.

These are similar goals, but on completely different scales and for different results. Their achievement and success depends on how the concerns or challenges are recognized and approached. We have economies of scale as a seed company with our network of growers, but the home gardener has some advantages that we would have a hard time taking advantage of, like keeping a locally adapted regional variety alive.

There are no one-size-fits-all best solutions to the availability of quality seed. A resilient, robust and diverse seed and food economy require home gardeners, regional and national seed exchange programs to participate alongside independent seed companies to contribute all of their unique advantages and skills. Only in this way can the full expression of the diversity and adaptability of open-pollinated seeds be realized and utilized. This might be considered the definition of seed quality!

An obstacle for the home gardener used to be the lack of access to solid, proven and reliable seed saving information and resources. There were lots of introductory articles, booklets, and classes on seed saving, but little in the way of intermediate or advanced classes, books, forums or articles for the home gardener. Thankfully, this is not the case anymore, as the internet has given the home gardener access to more detailed and advanced information.

A few examples are Seed Savers Exchange, an excellent resource for the home gardener to learn from and exchange seed stock with. There are also online resources usually used by seed professionals but accessible by anyone such as GRIN, the Germplasm Resources Information Network of the USDA and PFAF, Plants for a Future. There are several books available that are excellent in their education of producing seeds; one is “Seed to Seed” by Suzanne Ashworth that has been one of the standards for seed production and saving for over 20 years. Another newer one is “The Complete Guide to Saving Seeds” by Robert Gough & Cheryl Moore-Gough, which covers flowers, trees, and shrubs.

In addition to the above-mentioned resources, as a seed company, we have access to our growers and other professionals – a group of experienced food and seed producers who have learned through years of training, experience and trial-and-error how to produce the best seeds to continue the traits and characteristics of each variety they grow. These resources are closely guarded, as a highly experienced seed grower is a very valuable resource for any seed company.

Challenges

When looking at the challenges of producing high-quality, viable seed in enough quantities for next year, both the home gardener and seed company face similar concerns. Seed quality should be the primary concern for both. Without high quality, true seed there would be too much variability in all aspects of agriculture, from seed germination, growth, health, pest and disease resistance, food production and the harvesting of more seed. The quality is achieved through proper management, isolation, harvesting, and testing ensuring the viability, vigor and growing true to type of next year’s seed crop.

Management methods

Management for the home gardener starts with the decision of how many plants to use for seed production as opposed to food production, which can be quite different. Ripe vegetables often have immature seeds, while mature seeds are normally found in inedible, overripe or almost rotting vegetables. Some varieties can produce both food and seed by simply letting chosen specimens ripen and mature their seeds on the vine or bush, while the rest are harvested for food, such as a perfect tomato tagged to let ripen for its seeds. Others will need to be kept solely for producing seed, such as a lettuce plant that needs to be allowed to bolt to set seeds.

Minimum Viable Population

A sufficient number of plants, called a minimum viable population, should be used to avoid a genetic bottleneck or the loss of genetic adaptability and diversity that inevitably occurs over time. Sometimes this is hard for the home gardener to do, as often there isn’t enough space for the population needed while allowing for other vegetables to be grown. Our tomato example serves here, as the minimum viable population is 100 plants, way too many for most home gardeners. The rule of thumb is that outcrossing varieties such as tomatoes need 100 plants as a minimum genetic population, while inbreeding ones like peppers need 20 plants. So what is a home gardener to do?

Even modest home garden seed production often results in much more seed than one gardener will use in several years. One very effective solution is participation in member to member seed exchanges either locally, regionally or nationally. This has the dual benefit of introducing a greater amount of genetic diversity to overcome a smaller plant population from any one garden while dispensing extra seed.

As a seed company, this concern is overcome by the number of plants needed to produce the quantity of seed for next year’s sales, and most seed growers who are also food producers have separate fields for seed production, so there is no conflict with seed vs. food growing.

Isolation and Selection

To keep seed quality high, isolation and selection are both used as part of quality management. Isolation simply means keeping two similar varieties, such as peppers, from cross-pollinating. Selection chooses the most desirable characteristics to save seed from or removes undesired characteristics from the seed producing population.

Isolation methods can be time, distance or physical. The time method is simply planting two cross-pollinating varieties at different times so that they aren’t flowering at the same time. Distance isolation involves planting far enough apart so that the pollen or pollinators cannot reach each other. Physical barriers prevent the spread of pollen from one plant population to another by cages, pollen sacks or socks, a thorough but time and labor-intensive approach.

Home gardeners often use time isolation by either planting at different times during a growing season, or only planting one variety each season. Distance isolation can become a challenge, depending on the size of the garden or property. Usually, only very dedicated seed savers will use physical barriers.

Our seed company utilizes a network of seed growers to solve the different seed crop isolation requirements. Time isolation is used by those with longer growing seasons while larger growers use the distance approach, having the needed space on their properties. Another solution is several growers producing different seed varieties at the same time. Physical isolation is used extensively when correcting undesirable traits in a variety, during grow-outs to re-introduce a new or rare variety or for traditional seed breeding and stabilization.

Selection is another aspect of quality management in seed production, with two approaches – negative and positive. Negative selection, or rogueing, removes undesirable aspects, characteristics or traits from the seed producing population to maintain the established variety. An example of this is a potato-leaved tomato. Any regular-leaved tomatoes growing in the row would be removed as undesirable for that particular tomato’s characteristics. Another might be the color of the flowers of a vegetable – the purple ones would be removed, as yellow is the color of the correct characteristics. Positive selection involves saving seed with desirable aspects, characteristics or traits such as a large, sweet, striped, early paste tomato. Positive selection over a period of a few years is how local adaptation can be enhanced for the home gardener, and new varieties brought onto the market for seed companies.

Both the home gardener and seed company grower would over-plant slightly to account for selection losses, and perform the selection process as part of their daily gardening and inspection activities.

Germination Testing and Trialing

Two final aspects of quality seed management are germination testing and trialing or grow-outs, which give proof of the seed sprouting quickly with lots of vigor and growth energy, growing true to type with weather tolerance, disease resistance and good production amount. This becomes “the proof in the pudding”, as it shows any weaknesses and confirms the desired characteristics of the variety being produced.

The home gardener can easily test the germination of the current crop of seed early in the winter, as most seed needs to dry completely and age a few weeks before showing the best germination. For most crops a moist paper towel in a sealed plastic bag works very well to test germination. The grow-out can be as a food crop next year so that the production and garden space are not wasted.

We as a seed company will either have the germination tests performed by the grower so that any issues can be addressed before the seed is shipped to us, or we will perform them once we receive the seed from our smaller growers. Either way, all of our seed is tested for germination prior to being sold to our customers. Next spring’s grow-out will be done either by us or the grower, depending on the grower, the seed variety and seed volume.

There are those that would argue that the heirlooms we have today are the result of families saving their seeds and passing them down from generation to generation. This is partly true, but only partly. We have the abundance of heirlooms today thanks to the families that saved them, the local and regional seed exchanges that helped keep them alive and the seed companies that grew them out, advertised them to a wider audience and sold them across the country.

Aunt Ruby’s German Green tomato is a perfect example – grown in northern TN for over 200 years, passed to a great-grandniece, they would have been lost if they hadn’t been passed to Bill Minkey who donated them to Seed Savers Exchange. They grew the seeds out, told their story and they survive today because of that collaboration. Another excellent example is that of the Concho chile from northeastern Arizona. It was grown in the tiny town of Concho, AZ for several hundred years after being traded by the Espejo expedition in 1563 to the local Hopi Indians. Around 2000 it was almost extinct with only a couple of families continuing to grow it. A local lavender farm resurrected it and shared the seeds with us, and we have helped it to reach all across North America and several other countries.

It took the effort of everyone – the gardener, the seed exchange and the seed company to keep these and many other heirlooms alive; one alone wouldn’t have been able to do it. This is the circle of life of the seed, along with those who care for the seed.

We are very happy to share an editorial that Stephen wrote for the Spring 2014 issue of Small Farmer’s Journal. SFJ, as it’s known, has had a large influence on us for a very long time. It is one of those jewels of a publication, wrapped up in its plain brown paper cover, but holding viewpoints and articles that expand one’s mind, or perfectly sum up thoughts on a subject, or inspire or educate on something that you hadn’t really thought about before.

We’ve contributed articles before, but were very honored when Lynn Miller asked for an editorial. He didn’t specify the subject, so we went with what was most in front of us at the time, drawn from a number of conversations with customers from all across the country, along with material from a couple of recent presentations. We hope you enjoy it!

Our perspective is somewhat unique, based as it is on contact with home gardeners and small scale growers across the US and Canada, along with a number of other countries. Our phone and email conversations are filled with happenings from all over, from cities with community gardens, church and school gardens, to chefs working with growers to bring fresh, sustainable and locally sourced food to the forefront of their cooking, to prison systems that are going back to raising some of their own food for the lower costs, higher quality food and better rehabilitation that a working garden provides.

Canning classes are oversubscribed, seed starting and planting lectures are full and ordinary people are beginning to ask about how to grow food without using so many chemicals, pesticides and herbicides because of their concern about what they are eating. It is no longer unusual to get an email asking if we are connected in any way to the bio-tech companies, if we use herbicides in growing our seeds or if our seeds come from China.

We are seeing many small, quiet but positive indications that give us hope and encouragement in what we, and those like us, are doing. While multinational industrial food companies continue to march in lockstep with the commercial biochemical industry to control the federal regulatory agencies tasked with keeping them in check, many individuals are rejecting the rhetoric, shrill hype and slick marketing to regain their own choices. As Wendell Berry wrote –

“We are going to have to gather up the fragments of knowledge and responsibilities that have been turned over to governments, corporations, and specialists, and put those fragments back together again in our own minds and in our families and household and neighborhoods.”

This is exactly what we are seeing, in many small ways, in every corner of our cities, towns and countryside across our nation. It encourages us and motivates us. These ripples have a cumulative effect, much like the 100th Monkey Principle, where a small group of primates were taught to peel their bananas from the bottom instead of the stem end. They were isolated and out of sight from the mainland, with no identifiable method of communication. Once a critical number of monkeys on the island were consistently peeling their bananas from the bottom, researchers noted that monkeys on the mainland started to do the same. Thus the term – 100th Monkey Principle – where populations change how they do things seemingly spontaneously.

We have no way of knowing where these ripples will end up, who they will affect or how. We do know that they create positive results that continue long after the initial effort or influence.

An excellent example is the Humboldt Elementary school garden in the small Arizona town of the same name. Started by a now-retired teacher almost 20 years ago that was abandoned for a number of years, then re-started last year by a new teacher, it has positively affected kids, parents and teachers already. The local paper has featured it, kids are actively engaged and eagerly look forward to their time in the garden each day, and the growing space is being expanded to grow more.

Whether the influence is simply an appreciation and preference for fresh, local food or extends to the choice to become a grower, rancher or farmer that is biologically friendly, we’ll never know and don’t really need to. Sometimes knowing that we’ve made our corner of the world a little better through our actions is enough. That knowing helps us keep moving on, continuing the work and sharing our knowledge, experience and passion with those who will listen and join with us. As the kid who was told that he couldn’t save all of the starfish washed up on the beach, he replied as he threw another one back, “It made a difference for that one!”

I heard or read the old phrase, “If you want to change the world, plant a garden” when I was much younger. It didn’t make any sense to me at the time, as I strongly disliked being forced to work in our large garden when I had much better things to do with my free time!

After I grew up, left the Navy and the big cities and made the conscious choice to move back to a small town, those words began to make more sense. The world-changing part wasn’t the garden or the food that it grew, not even the world that it was supposed to change. Obviously, one small garden can’t change or feed the world by itself.

What one small garden can do is share.

It can share its food, the knowledge of how that food was grown, why it tastes as wonderful, rich and delicious as it does and the excitement and contentment that only comes from food you’ve grown. The term “local food” becomes something entirely different and ceases to be a carelessly used sound-bite. That one small garden can become a few, then several, then many across a town, a city, a county and a nation. That small garden becomes a metaphor, an idea and a movement.

It can become the embodiment of how we as individuals can reclaim our decisions from the proxies of government, corporations and stockholders and make it a personal choice to grow our own food and share it with our family, friends and neighbors, improving everyone’s lives that we share. After all, we are only talking about the third most important ingredient in life, after air and water! Food, as with soil, has been denigrated and degraded into a commodity that is not worth our attention, respect and devotion. We are slowly waking up to this fallacy.

Something as simple as showing someone the distances between home-grown and store-bought food through the flavor and nutrition can open their eyes to a new world of food.

Sharing our abundance from the field or garden with a friend or neighbor is a powerful way to start a ripple. For us it costs next to nothing as it is surplus, but is worth a lot to the receiver. They want to reciprocate the sharing as a way to say thanks. This creates a very powerful, positive ripple effect that used to be common in rural and agricultural communities and is becoming more widespread once again.

This occasional sharing becomes something much greater when the surplus is planned, such as an extra row that is planted exclusively to give away or share with others. This creates a very positive upward spiral in the community, as well as strengthening it and making it more resilient and self-supporting.

Others follow the example, as they want to contribute and participate in the abundance. Soon the immediate neighborhood begins to look a lot like Switzerland, where neighbors plan their backyard gardens together to maximize the amount of food grown in their area, and then share the crop together. What is surplus then goes out to the larger neighborhood or community; a perfect demonstration of how to get away from the insidious influence of the industrial petro-chemical agri-business that seems bent on controlling our food supply today. The most deadly effective way to loosen their grasp is by making them completely un-necessary in our lives.

Looking at the marketing machines of mass media backed by billion dollar multi-national corporations and aided by the federal government, many everyday people question the continued existence of individual choice and responsibility today and whether it has any application in our lives. It is a valid question, but the answer won’t come from looking at the usual answers.

Look instead at some of the results that have happened from individual’s choices and actions. How rBGH was pushed out of milk in grocery stores due to mothers continually asking for milk without that synthetic hormone, and asserting that they wouldn’t buy any milk that had it. Enough dairy managers heard the questions, passed it up the line and the management board saw that enough market share and dollars were being lost that they made the business decision to remove it. It is estimated that 7 – 10% of the population of moms made this happen, not a majority in a voting situation, but a large impact on the company’s profits that made the choice clear.

Look also at how hard the processed food industry, helped by the bio-tech industry has fought to defeat GMO labeling initiatives in California and Washington states. The commercial, industrial Ag industry has called these “defeats”, but was forced to spend tens of millions to achieve those victories. Their behind the scenes efforts have been exposed to the public, their “Natural” label subsidiaries that helped fund the anti-labeling efforts have been hit hard and repeatedly, feeling the effects of public outrage as more individuals learn of the corporate shell game being played at the expense of their health and money.

From our perspective, we see much to be proud of, yet much to be very concerned with.

The local, sustainable food movement has seen great growth and increase in popularity and acceptance that has been beneficial to small farmers, growers and communities; at the same time there is more rhetoric being lobbed at the “opposition” from both sides than ever before.

Civil discussion is becoming increasingly more difficult with catch-phrases and sound-bites being deployed instead of rational, thoughtful and open discourse where everyone doesn’t have to agree, but can still get along. Shrilly shouting down the other party with emotional, highly charged word bombs or character assassination is the order of the day. It seems that more folk are content with term-slinging that makes them feel good or righteous, instead of actually understanding what those terms mean or describe.

We see more need for resiliency today than ever before, but for entirely different reasons. Resiliency once was used somewhat interchangeably with self-sufficiency, and it still applies in that respect.

I once heard a great example of resiliency – that of a cabin boy taking a cup of coffee to the captain on the bridge. As the ship is pulling out of port in calm waters, it is an easy task – cup of coffee on the tray, don’t run into anyone, be careful going through the doors and all is well.

Everything changes when he has to do the same thing in 8 – 10 foot seas with a storm moving in with the ship anything but still and calm. Every move, every step must be planned, visualized and then executed with confidence. Elbows, knees and shoulders are used to brace against bulkheads, crossing from one side of the passageway and from one wall to the other as the ship rolls is now normal. Waiting until the top or bottom of a swell before going through a door and bracing himself all the while is what is needed.

The same task or plan under different circumstances makes doing that task completely different.

As Allan Savory taught in holistic management – the very last question of any planning is to ask, “What if we are wrong, what are the early signs that things aren’t working?” Don’t assume that everything will go as planned, and that we have all the answers at the beginning. Don’t assume we are always right.

Our country does not have the resiliency that is needed in so many areas today. Look at recent weather events, with people stranded on the freeways in Atlanta, unable to get home, staying at big box hardware stores overnight, running out of fuel on the freeways. Our stubborn insistence on depending on someone else to provide for us will eventually get us into real trouble.

Another example we should have learned from long ago, but were re-taught during the economic meltdown and ensuing political madness of “The Great Recession” that crashed around us in 2008 was the fallacy of infinite growth, as if the financial markets were not a closed system and existed outside of the realities of the world.

I’ve often said that we will wind up in a sustainable economy with a sustainable agriculture – either by force or by choice. We will either make the choices and changes needed to be able to grow enough of our own food to feed ourselves, or we will suffer until we do learn how to when times get tough. We might be seeing the arrival of those times with food starting this summer, with California in a state of emergency due to severe drought and an estimated 50% of US-grown combination of fruits, nuts and vegetables from there. California grows 70% of the national production of fresh vegetables, according to the CA Dept. of Food and Agriculture for 2012.

For a real-world example of resiliency in action, look at Russian Dacha gardening. This is backyard gardening on a national scale that prevented a famine after the USSR collapsed, taking with it commercial, industrial, subsidized agriculture. They produce 47% of their national food supply on 3% of the land, from home gardens and they’ve done this for hundreds of years with hand tools and human labor. According to official government statistics in 2000, over 35 million families (approximately 105 million people or 71% of the population) were engaged in dacha gardening. These gardens provide 92% of Russia’s potatoes, 77% of its vegetables, 87% of the berries and fruit, 59% of its meat and 49% of the milk produced nationally, in a nation that has an average of just less than 100 days of growing season a year. So tell me again, please, exactly how small scale agriculture doesn’t work?

Would we in the US fare as well if the cost of diesel fuel doubled or water scarcity significantly increased food costs? Or would we go the way of the Cubans, where a significant portion of the population died of starvation and everyone else lost 30lbs until they figured out how to grow food in the cities; using every available scrap of soil, planters, lawns, parks, flower beds and spots from curb to sidewalks to grow enough food to feed themselves.

So, what can we do as individuals? Can we truly make a difference? These questions always, inevitably arise in these discussions. The answer is – of course we can make a difference, we already do each and every day that we share our knowledge and abundance, that we create those positive ripples, sending them out into the world to reinforce other ripples from unknown people just like us.

This isn’t just some socially responsive, feel-good response. Looking around us and seeing the unprecedented growth of Farmer’s Markets, community supported agriculture (CSAs), food hubs, community gardens, school gardens and backyard gardens shows us something that terrifies the conglomerates – people are becoming interested in their food once again, and are tired of being lied and marketed to by the industrial food corporations and their lackeys in the government.

It is a radical thought in today’s world where the health care industry pays no attention to food while the food industry pays no attention to the health of their products that improving and healing the soil in our gardens and farms and growing some of our own food will noticeably improve our own health without the costs, paperwork or side effects.

Looking at it from that perspective, it really feels good to be a radical, doesn’t it? After all, if you aren’t on some sort of government watch list these days, you really aren’t trying hard enough!

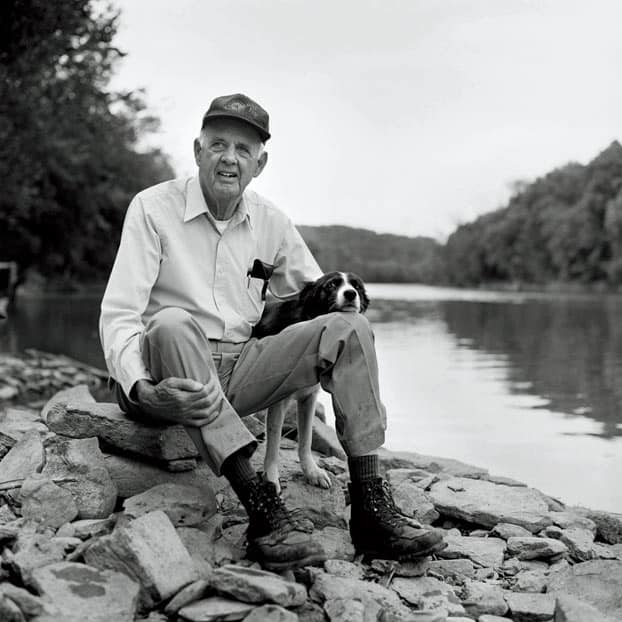

Wendell Berry – Poet, Author, Farmer, Philosopher

Let’s start this conversation off with one of Wendell Berry’s quotes that has had a profound impact on me and what has become Terroir Seeds:

“We are going to have to gather up the fragments of knowledge and responsibilities that have been turned over to governments, corporations, and specialists, and put those fragments back together again in our own minds and in our families and household and neighborhoods.”~ Wendell Berry

I heard or read the old phrase, “If you want to change the world, plant a garden,” when I was much younger. It didn’t make any sense to me at the time, as I strongly disliked being forced to work in our large garden when I had much better things to do with my free time!

I do remember the planting time during spring – readying the rows, digging the small irrigation ditches, making sure that the water would flow all the way to the end of the row. Then the planting of the seeds and transplanting seedlings into their places. We watered our 1/4 acre garden with a gas powered well pump from an old abandoned well that we had cleared up and found water in.

Neither of my parents came from farming or ranching backgrounds. My father wanted to grow our own food because of his concern about the health of grocery store produce in our small town and the proliferation of commercially prepared foods. This was the late 1970s and early 1980s. Most of the knowledge that we used came from our Mother Earth News subscription, along with the advice of a couple of older family friends. Looking back, I see that there was a distinct lack of knowledge and experience even then, but there was a desire to do something different. For all of his faults, my father had it right this time.

Ours was a typical “spring and summer” garden. We planted as soon as we could in the spring and then watered, weeded and waited until the garden came alive and threw way too much produce at us. Then it was cooking, canning and drying seemingly non-stop until the garden sputtered to a stop, usually after the first couple of hard frosts. After that we cleared the dead plants away and waited until the next spring to try again. I remember the dreaded summer break routine of hoeing and weeding after breakfast until it got hot, then again in the late afternoon into early evening. We were gardening in soil that had been fallow for decades, so the seed bank of weeds was tremendous. We didn’t really understand how to manage soil fertility, so we hoed and pulled weeds constantly.

After High School I joined the Navy and left the small town behind just as soon as possible. Six years later – after lots of travel, some growing up and the Gulf War, I left the Navy, the big cities and a failed marriage behind and made the conscious choice to move back to a small town. That was when those words about a garden began to make more sense. I began to realize the world-changing part wasn’t the garden or the food that it grew, not even the world that it was supposed to change. Obviously, one small garden can’t change or feed the world by itself.

I learned the magic of what one small garden can do is share.

It can share its food, the knowledge and experience of how that food was grown, why it tastes as wonderful, rich and delicious as it does and the excitement and contentment that only comes from food you’ve grown. The term “local food” metamorphoses into something entirely different, ceasing to be a carelessly used sound-bite and growing into many delicious food bites that nourish us – body and soul.

That one small garden becomes a few, then several, then many across a town, a city, a county and a nation. That small garden becomes a metaphor, an idea and a movement. That small humble garden becomes a much-needed, deep seated sense of security in a world where very little has the feel of permanence or security today, regardless of social status or financial standing. It gives us grounding and a sense of place, of belonging to and being part of something much bigger, older and better than us.

That small backyard home garden becomes the embodiment of how we as individuals can reclaim our decisions from the proxies of government, corporations and stockholders and make it a personal choice to grow our own food and share it with our family, friends and neighbors, improving everyone’s lives that we share. After all, we are only talking about the third most important ingredient for life, after air and water! Food, as with soil, has been denigrated and degraded into a commodity that is not worth our attention, respect and devotion. We are slowly waking up to this fallacy.

“Odd as I am sure it will appear to some, I can think of no better form of personal involvement in the cure of the environment than that of gardening. A person who is growing a garden, if he is growing it organically, is improving a piece of the world. He is producing something to eat, which makes him somewhat independent of the grocery business, but he is also enlarging, for himself, the meaning of food and the pleasure of eating.”~ Wendell Berry, The Art of the Commonplace: The Agrarian Essays

When we garden, we take an active part in the production of our food and quit passively waiting for it to be grown, processed and delivered to us on our whim. As Joel Salatin said in Folks, This Ain’t Normal, “The average person is still under the aberrant delusion that food should be somebody else’s responsibility until I’m ready to eat it.” Even the smallest container garden starts the reconnection process for that person. They learn and observe what it takes to grow even the smallest amount of food, whether it is a single plant of leaf lettuce or a handful of kitchen herbs. Through success and failure, they begin to realize that food doesn’t just pop into existence at the grocery store regardless of seasonality or weather conditions.

The very act of gardening on any scale forces us to pay attention to the world around us, to observe what is happening and learn more about the interconnected nature of all things. We become aware – perhaps for the very first time- of the enormous complexity of our world, and the realization of the folly of simplistic, reductionist, single solution thinking when applied to complex systems, even such a small one as a garden.

That awakening can be the most beautiful, wondrous experience or one of the most frightful of our lives, depending on how we react and adapt to change. For those who come to see the beauty in growing food, their lives will never be the same. They will acquire a quiet sense of accomplishment, of progress and resiliency that is almost impossible to describe or talk about, but is implicitly understood by another who has made the same journey, whether as a child in a farming or ranching family or one who has made the conscience decision to take the road less traveled.

Our tech driven, always on, instant gratification society is shown to be artificial when we learn that we absolutely cannot plant carrot seeds the day before we want to serve carrot salad to our dinner guests. Everything takes its own time and there are things in life that absolutely cannot be rushed, “right sized”, or optimized to serve our timeline and agenda. As advanced a society as we are today, with as much progress as we’ve made, we are still human beings in a world that is larger than us, that doesn’t march to our drumbeat.

When we begin to garden, we begin to heal our part of the world starting with our own space and lives. As we gain knowledge, experience and success we can start to apply those lessons learned in the garden to other areas of our lives and offer our hard-won experiences to others so that they can hopefully learn from our mistakes. We come to re-connect with the idea that we belong in the world and to the world; we are not separate from and should not be disconnected from it. The idea that human kind shouldn’t be in the wilderness or nature is fully revealed as folly as we learn that not only are we part of the world, we are inseparable from it, no matter how hard some of us try. Rachel Carson said it so well, “Man is a part of nature, and his war against nature is inevitably a war against himself.”

To look at it from a different angle, I leave you with this thought that brings us full circle to the beginning of our conversation:

“Until we understand what the land is, we are at odds with everything we touch. And to come to that understanding it is necessary, even now, to leave the regions of our conquest – the cleared fields, the towns and cities, the highways – and re-enter the woods. For only there can a man encounter the silence and the darkness of his own absence. Only in this silence and darkness can he recover the sense of the world’s longevity, of its ability to thrive without him, of his inferiority to it and his dependence on it. Perhaps then, having heard that silence and seen that darkness, he will grow humble before the place and begin to take it in – to learn from it what it is. As its sounds come into his hearing, and its lights and colors come into his vision, and its odors come into his nostrils, then he may come into its presence as he never has before, and he will arrive in his place and will want to remain. His life will grow out of the ground like the other lives of the place, and take its place among them. He will be with them – neither ignorant of them, nor indifferent to them, nor against them – and so at last he will grow to be native-born. That is, he must reenter the silence and the darkness, and be born again. ~Wendell Berry, The Art of the Commonplace: The Agrarian Essays

The co-founder of Slow Food International, Carlo Petrini took the stage after the opening ceremonies at the Slow Food USA delegate meeting during the 2012 Slow Food Terra Madre and Salone del Gusto conference in Turin, Italy this past October. He gave his remarks to about 230 delegates from all across the USA who are working daily on the core tenants of “Good, clean and fair” food for everyone. It was impressive to see the amount of passion, dedication, talent and genius gathered together in that room, all for the sake of one of our most important yet overlooked foundations of life; food.

Carlo seemed to be impressed as well, with comments like “What you’ve done in America is extraordinary, not just for the USA but for the rest of the world. A Slow Revolution toward respecting food, a deeper appreciation of food that serves as an example for the entire world.” He went on to say that we’ve helped “Achieve the most important thing that Slow Food needs to achieve – given back a holistic sense of food.” We’ve started to show that food is not and never can be a commodity, merchandise, just a price point.

Its story is important – the memory, the people and its history. By reducing food and everything about it to its commodity values of productivity and profit, we are approaching a brink. That brink is the loss of diversity, not only of the varieties of foods that have nourished us for thousands of years, but the loss of human and cultural diversity as well. Those different types of diversities have enabled us to withstand and overcome many different challenges over the millennia, adapting and growing stronger in the process. Without all of those diversities, we are all weakened and more vulnerable to changes, whether expected or unexpected, human or natural caused.

Carlo closed by saying that the people of Slow Food have the holistic vision of the path back to the healthy diversity that will make our food and our communities whole again. Slow Food delegates practice that vision daily, working to strengthen our food connection everywhere we are, every day. Watch the video and see Carlo’s thoughts for yourself!

We need to build a better world, you and I. There has never been more of a need than there is today. There has also never been a better time. There is an old saying, “The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second best time is today.”

A better world where our lives make sense, where we stop working longer hours in jobs we detest to buy things that fill our homes but don’t and can’t make us happy. Where we realize that we – not things and not money – make ourselves and each other happy. Our lives are better when we work with others, helping them while helping ourselves at the same time. A world where what we do engages us and what we love, and that work fulfills us and gives us and the world meaning. Where both parties in each and every transaction benefit, and the first thought isn’t “what profit is there for me?” and the dollar isn’t the sole measure of benefit, profit and satisfaction.

There are many critical systems that are in decline or are breaking, but do not give up. Depending on where you look and what you read the world is on the brink of catastrophic collapse in many areas; finance, food, energy, water and populations are all at risk. There are dire predictions of dark and difficult times ahead, but do not give up.

These circumstances are precisely why you and I must build a better world. We must begin today. Very few people have a positive outlook for the next 5 to 10 years, but we can change that. When questioned, those same people give the reason for their pessimistic outlook as due to the state of the world and to circumstances created by governments and corporations. In other words, they are afraid of external circumstances beyond their control.

We start building a better world by realizing, recognizing and taking responsibility for the only thing that we truly have control over in our lives – our choices. We always have the power of choice. We constantly choose, for better or for worse. Several hundred times a day we make a choice. Our choices affect not only us, but those around us and multitudes of others we will never meet. There are those that say that one person cannot make a difference. This is untrue. One person, alone, will have a difficult time making a difference. However, we are very rarely truly alone – especially in our choices. Our lives are the direct results of our choices, made throughout the years that have lead us to this place in time where we are today. Who we are, what our character is, what we do in life, where we live are all the results of choices we have made.

Our most powerful choice to build a better world may be one that we make with little thought every day. Our choice of how and what to spend our money on is one of those paradoxes that goes largely unnoticed and unexamined in our lives. Both Joel Salatin and Michael Pollan have said that we vote with our forks three times a day. Many of us have heard the “Buy local” and “Know your farmer” mantra, but what does that mean?

What it really comes down to is taking the responsibility of who you support with your dollars. Every time you make a purchase, you are financially helping that company, along with endorsing the way it does business. For better or worse, this is what happens. Do you love the eggs, greens and tomatoes from the young farmer at the Saturday Farmer’s market? Wonderful! Buy them and you directly help that company stay in business and grow. Are you upset at how many jobs have been sent to China, and the newly introduced GMO sweet corn in Wal-Mart? Good! Do you buy anything from them? If so, despite your disagreement, you are helping them to stay in business and grow. It really is that simple.

Realize, though, that simple almost never means easy. It can be tough to make good choices. This is one of the reasons we are so passionate about small business and human scale living. Our individual purchases means very little to a large international corporation, but means a lot to a small family owned farm or business. There is a quote that sums this up nicely –

“When you buy from a small mom or pop business, you are not helping a CEO buy a third vacation home.

You are helping a little girl get dance lessons, a little boy get his team jersey, a mom or dad put food on the table, a family pay a mortgage, or a student pay for college.

Our customers are our shareholders and they are the ones we strive to make happy. “

This can seem daunting at first. There are so many choices about so many things that we don’t want to get wrong, we don’t know where to start. There is also so much negativity around, it can seem to be simply too much. Start small, start by focusing on and emphasizing the positive choices that we can make today. We won’t build a better world by getting rid of the negatives; we will build it by focusing on and increasing the positives. When more of a positive nature is added to a system, it will naturally and automatically become better as the positive displaces the negative. What we focus on – positive or negative – think about, talk about and act on will grow. Help grow the good in our lives. Find good, positive ideas, thoughts and directions, and then incorporate them into your life. It takes some work to concentrate on the good and beneficial, but once those habits are started they will continue to help.

Do not make the mistake of thinking that you cannot make a difference. Never underestimate the power of change inherent in a small effort, movement or idea. Committed people make the difference on a large and small scale every day. As the famous quote from Margaret Mead goes –

“Never underestimate the power of a small group of committed people to change the world. In fact, it is the only thing that ever has.”

Start by finding and working on what you can do, not what can’t be done. Build a better life, starting with your life. Plant a garden at home, no matter how small. Container gardens are great, they are simple to set up and use and can grow some good food. Help out at the community garden, with or without a plot of your own. Share your veggies with a neighbor, family or friends. Help out at the food bank, Meals on Wheels, or your local soup kitchen with donated veggies or your time.

Be on the lookout for opportunities to enrich and improve your life. Stop thinking about the dollar value in each opportunity, and make the decision to take it or not based on how much positive or good it will bring to your life and others. Read more. Read to learn and not just for entertainment. Study your environment and habitat where you live. Get to know what grows wild there. Find out what is edible and what is not. Learn what edibles will grow well with little care and plant some. Start a food forest in your yard or neighborhood and share with those around you. Make a point of getting to know someone new at the Farmer’s market, or going to the Farmer’s market if you don’t already go. Learn what is made in your community or town. You might be surprised at what you don’t know about where you live. Once you start getting to know more about where you live, you just might find that you like it more than you initially thought.

These are some of the ways you and I can build a better world. We can start today.

Unleash the flavor of the past with heirloom seeds. Find out how these seeds can bring back memories of delicious, homegrown produce.

Two of the most important ingredients in growing food are healthy, fertile soil and good quality seed. As gardeners and growers, there is often an arc in the quality of both that directly corresponds to the arc of knowledge and experience of the grower. At first, most home gardeners will start out buying seeds from almost anywhere, without the realization that all seeds are not the same in terms of quality, but also germination and vigor in production. As time goes on, experience and knowledge are earned, and the grower becomes increasingly particular in selecting the seeds that they want to grow from. They usually get to know a company and the performance of their seeds, either through a friend or by experience. We all know the definition of experience, right? Experience is what you get when you don’t get what you want!

This is a type of question that we receive a lot- how are your seeds grown? are they organic? are they well-suited to my climate? do you grow your own seeds, or buy them? Most of the time, the real question is- What is the quality and performance of your seeds? How do I know that I am getting the best possible quality at a reasonable price? Most gardeners and growers that have some years of growing behind them realize that the best, “guaranteed lowest” price is often not at all. Paying $2.00 for a packet of seeds vs. $3.50 a packet may seem like a good deal, but there is more than just the price that must be looked at. If that $2.00 packet has 10-15 seeds and the $3.50 one has 45 seeds for a tomato or pepper, and knowing that high quality tomato seeds will last at least 2-3 years in good storage conditions, then the “more expensive” packet is a much better buy, as it is half the price, when comparing equal amounts of seeds. Or when comparing prices, there are 2 to 3 times more seeds at the same cost. Plant what you need this year, share some with friends and neighbors and you’ll still have enough to plant with next year, maybe the year after that. This is good economy. Long ago, Cindy and I realized that we would never be wealthy enough to afford to buy cheap quality. Let me elaborate. Boots that cost twice as much new, but will last 3 times as long and can then be rebuilt for another service life is money well spent, over saving some dollars today, but being forced to buy the same boots 3-5 times over the same time period. Another benefit of quality is … quality. The better quality will be more enjoyable to use, work better, or grow better with more flavor, nutrition, resistance to pests and diseases or weird weather patterns.

We have just returned from visiting two of our growers in California, and have some good photos that illustrate the differences between high volume, mass-produced seeds and how ours are grown, harvested and cleaned. One of our growers is also a mentor to us; a highly respected traditional plant breeder, introducing the Chocolate and Green Pear tomatoes last year; and an acknowledged expert in seed saving and seed purity. We turn to this grower to identify and correct problems that show up with heirlooms. The other grower is a larger seed grower that we contract with; we are a small portion of their total seed production. Yet they take the time to get to know us and their quality control processes, ensuring that their seed meets our quality criteria.

Let’s look first at commercial, conventional seed production. We will use tomatoes as the example, as they are in season right now, and show the amount of work required to produce the quality needed for heirloom seeds.

Large tracts of land are planted by machine (usually with hybrid varieties) and grown until ready for harvest. There is too much acreage under growth for any hand work, so periodic spot inspections are carried out throughout the season. When it is time for harvest, a large tomato combine machine is pulled by a tractor down the rows to harvest the tomatoes. All of them, regardless if they are fully ripe or not, or if they are smaller or under-developed. The plants are separated from the fruit by a huge vacuum, then the tomatoes are transferred to a gondola bed pulled alongside, to be hooked to a semi truck and transported to the processing facility. Above you can see the double gondolas pulled by a tractor. If you look closely, you can see the people in the cabs to get a sense of how big the equipment is. The transfer spout of the combine can just be seen over the top front of the lead gondola.

This is a rear view of the same combine/gondola. The tomatoes are falling into the gondola, and the remains of the tomato plants are left behind the combine. From here the tomatoes will go to a large crusher to separate the seeds from the rest of the tomato. The seeds will be washed and fermented to remove the gelatin coat, washed again, dried and packaged for shipment to the seed company. The tomato remains might be used for animal feed, or composted.

The challenge from a quality standpoint is that there is no selection possible in the field, it must be done at the processing facility- probably from a conveyor belt with people on both sides, looking for rotten tomatoes and debris. They won’t select for the largest and best of the variety, the ripest and tastiest, as there are simply thousands of tomatoes rolling past fairly quickly. They won’t be able to feel the tomatoes, picking out the ripest and most ready. Nobody will taste the tomatoes to check for flavor and ensure that it holds to the standard for that variety. No one will inspect them for the visual characteristics that make that specific variety unique and valued. The goal is to capture all of the seeds possible, as that is how the grower is paid- by the weight or volume of seeds.

This is in direct contrast to how our seed growers operate. They have smaller plot sizes that enable them to better control various factors and observe growth, flowering and fruit set patterns often and make needed changes during the season. The smaller plots also allow better isolation by time, distance and/or physical barriers to prevent cross pollination that would result in hybridization. This is one of the key factors in ensuring the highest quality seed possible.

Our growers inspect the growth of the tomato plants frequently, and remove any that are stunted, or show abnormal growth. This is done several times throughout the growing season, as flowering happens, and again during fruit set. This technique is a process of specific selection of traits or characteristics throughout the growing process- growth patterns, flower color, fruit size, color, shape and taste. It is labor intensive and requires a lot of handwork and hours in the field, but results in a superior seed. The tomatoes are harvested by hand with the fruit selected for the largest, best characteristics of the variety, best flavor and production right there in the field. The tomatoes are either processed in small batches by hand, or in larger batches by machine- depending on the grower and the volume of production that they do. Either way, there are more hands and eyes on the tomatoes than commercial processing, as there are significantly fewer fruits in the workflow. After separating the seeds from the tomato, the seeds are fermented to remove the gel coat, screened, washed, dried and inspected one last time before being packed for shipping to us.

Production growing for seed only happens after trials to determine viability, suitability and quality of that variety. Some of the trials take a couple of years before seed production begins. We don’t want to offer an heirloom that does not offer superior flavor, growth and resilience characteristics. In all of the selection processes, flavor and taste are at the forefront of the decision process. We have had a couple of instances when our grower called and said that we shouldn’t offer the variety because the flavor was not remarkable enough to qualify as an heirloom, or did not exhibit the flavor profile that it was known for. That means an entire growing season is lost, and the trouble-shooting begins, but it is better to lose a year or more than to offer an inferior quality variety. All of our seed production is focused on home gardeners and small scale growers such as Farmer’s Market and CSA growers.

Now that you have the answer to the questions above – What is the quality and performance of your seeds? How do I know that I am getting the best possible quality at a reasonable price?- you understand more of our processes and commitment to the quality of our seeds that we offer to you, our customer.

We were able to catch up and reconnect with an old friend recently- Dr. Gary Nabhan. He is one of those self-effacing geniuses that are as interested in learning from those he meets as he is in sharing his experiences for their benefit. An internationally recognized, award-winning chile-head, his eyes lit up when I handed him a seed packet of our Concho chiles and a baggie containing a few of these relatively unknown, wonderfully addictive chiles. We spent a few minutes discussing the convoluted history of the introduction of chiles to America, as well as catching up on news.

Gary’s curriculum vitae reads like a book in itself-

“Gary Paul Nabhan is an internationally-celebrated nature writer, seed saver, conservation biologist and sustainable agriculture activist who has been called “the father of the local food movement” by Mother Earth News. Gary is also an orchard-keeper, wild forager and Ecumenical Franciscan brother in his hometown of Patagonia, Arizona near the Mexican border.

He is author or editor of twenty-four books, some of which have been translated into Spanish, Italian, French, Croation, Korean, Chinese and Japanese. For his writing and collaborative conservation work, he has been honored with a MacArthur “genius” award, a Southwest Book Award, the John Burroughs Medal for nature writing, the Vavilov Medal, and lifetime achievement awards from the Quivira Coalition and Society for Ethnobiology.”

He works as most of the year as a research scientist at the Southwest Center of the University of Arizona, and the rest as co-founder-facilitator of several food and farming alliances, including Renewing America’s Food Traditions and Flavors Without Borders.”

For those that aren’t familiar with the term, here is the classic definition: Terroir: noun, the specific conditions of soil and climate of a place where a food is grown that imparts unique and special qualities or characteristics to that food. Also known as the “sense or taste of place”. Origin: French: literally, ‘soil, land’.