Potting soils come in all shapes and sizes, with most touting some form of “Organic & Natural” on the bag – but are they really certified organic? Do those potting soils really work as advertised and contain healthy, wholesome ingredients to help your precious seedlings get that critical head start they need?

To answer these questions and more, we bought a few bags of potting soils from our local sources, brought them home and opened them up to take a close look at what is there. We looked at the bag and labeling, seeing what is being sold and why, what wording and marketing is being used and if they stood up to closer scrutiny. One of those potting soils we have used for a few years, so we let you know of our past experiences.

Please note – this article is in no way meant to be a comprehensive, exhaustive laboratory research and review of all potting soils available to the average home gardener. There’s just no way for us to do that, as many are only regionally available and the ingredients change from region to region in the bigger brands.

As with our seed starting mixes article, we suspect there are a few companies producing potting soils for different markets with unique branding and bagging for each channel. We saw this with one product – one bag design and color set for the big box stores and another one for the smaller independent garden centers. This only underscores the need to read the labels, know what the descriptions, ingredients and marketing-speak mean and be able to decide for yourself if that particular bag will work for you and is worth the cost.

As with our seed starting mixes analysis, we found confusing and sometimes misleading labeling.

What are potting soils and do I need to use one?

Potting soils are traditionally what seedlings are transplanted into from the seed starting mixes. The seed is germinated in the seed starting mix, then when it is 3 – 4 inches tall and starting to put on its second or third set of true leaves, it is transplanted into a potting soil. Potting soils have nutrients which are missing in the seed starting mixes, continuing the growth of the seedling by feeding and supporting the root structure it is starting to develop.

What goes into potting soils varies widely, from a basic seed starting mix with some aged compost added for plant nutrition to full custom blends with compost, soil and nutrients coming from different ingredients – all to supposedly help the seedling grow stronger and faster.

Not everyone needs potting soils, as some have the space and materials availability to create an excellent rich, aged compost to use as the starting point of mixing their own special blend, while others just don’t have the time, space or materials available to do that.

Let’s take a look!

The first of the potting soils we found was the Kellogg Amend Organic Plus at Lowe’s and it’s available at Home Depot as well, so it should be available in most big box stores in the western US. We were interested to see what was in the bag and do some testing, as we’ve had several of our customers email us in alarm after transplanting into the Amend potting soils and within a few hours the seedlings were almost all dead or severely wilted. We found a commonality with most of them using the Kellogg Amend potting soils, but haven’t heard anything negative in the past couple of years.

As we mentioned in our seed starting mix article, we are not impressed with the words “Organic” or “Natural” on bags of soil, so seeing “Organic Plus” prominently splashed across the bag was an alert for us. It is branded as a garden soil for flowers and vegetables.

One label that did catch our eye and add to the intrigue was the OMRI listing on the bottom left of the bag. This indicates the contents are certified for organic food production, and are the equivalent of a “Certified Organic” label on food.

The OMRI label piqued our curiosity because our previous research as to why the Amend potting soils were killing seedlings led us to the fact that Kellogg had been using bio-solids, or treated municipal sewage, and possibly industrial runoff or wastewater. This easily explained why the seedlings died when transplanted into the potting soil.

So the question was – is this the same potting/garden soil, and if so, how is it OMRI listed?

In doing some reading, it appears Kellogg has used bio-solids or treated municipal sewage as a major ingredient in its composting program for a number of years. It seems that their OMRI listed products do not have any bio-solids as an ingredient in their products, but you can’t tell from the label.

In looking at the OMRI listing for Kellogg Amend garden soil, we found it is listed but with restrictions. OMRI lists it in the category of “Fertilizers, Blended with micronutrients” with the restriction being –

May be used only in cases where soil or plant nutrient deficiency for the synthetic micronutrients being applied is documented by soil or tissue testing.

Kellogg’s Amend product page has this to say about their OMRI listing –

Proven Organic

All of our products are listed by the Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI), the leading non-profit, internationally recognized third party accredited by the USDA’s National Organic Program (NOP). That means every ingredient and every process that goes into making our products has been verified 100% compliant as organic, all the way to the original source. Look for the OMRI logo on the bag, ensuring every product is proven organic.

All in all, it is OMRI listed – even with the discrepancies between Kellogg’s product information and the OMRI listing itself with the restrictions.

The OMRI listing is displayed in the lower left part of the bag, underneath the info box of what it is supposedly derived from and what it is good to use it for.

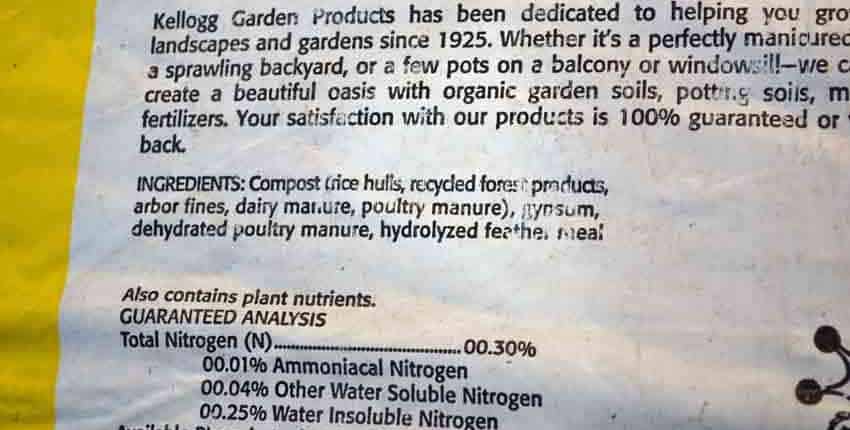

The ingredients list compost as the primary ingredient with what makes up the compost. Recycled forest products are typically a blend of finely ground wood from leftovers of the timber industry. Arbor fines are finely ground tree trimmings. Hydrolyzed feather meal is crushed and boiled poultry feathers, used as a source of nitrogen.

Dairy and poultry manure sound fine, until the source is looked at a little closer. What is the source of the dairy and the poultry manure? There is reasonable concern as to what is contained in the manure of animals from confined feeding operations – there are antibiotics and hormones used in the day to day operations which are passed through in their manure. Another concern is the possible presence of industrial herbicides and pesticides used in conventional grain production, which can easily be passed into the manure.

These are things to think about, especially if you want to grow as organically as possible.

One of our biggest initial concerns after getting it home and looking up both the Kellogg’s product listing page and the OMRI listing showing the restriction is there is no mention anywhere of the “synthetic micronutrients” from the OMRI listing on the bag or Kellogg’s website.

What are those synthetic micronutrients, and what is their source?

On opening the bag we noticed it was moist and had some white mold spots on the woody material in the mix. This is not a bad thing, molds and fungi work to break down wood into more available nutrients. Woody material helps to boost microbial activity to do just this.

The bag had a rich, woody aroma but did not smell of raw or partially decomposed manure. It was a dark, rich brown verging into almost black.

A handful of the soil felt light and porous with a slightly damp feeling to it. There was a trace of dark residue left on the fingers after rolling a handful through the fingers and getting a feeling for it.

On closer inspection, it is easy to see the woody residue of various sizes. Even though it is advertised as a soil, it was fairly light in texture without the more solid structure needed for long term growing of plants.

The white mold can be seen in the top right of the photo.

The next bag we opened was Miracle-Gro Organic Choice. We also picked this up at Lowe’s and have seen an impressive selection of Miracle-Gro products at Home Depot as well, so any big box store will have this line. We’ve also seen this brand at every garden center, hardware store garden aisle and landscaping supply store we’ve visited. It’s hard not to find them.

Again, the word “Organic” is used as a marketing tool in the word choice for the name. This is advertised for use with in-ground vegetables, fruits, flowers and herbs. It has the “Natural & Organic” term next, above a statement that it will grow fresh vegetables in your backyard.

So far, pretty standard stuff and not really any different than the next pile of bags at the big box store.

Our concern with this Miracle-Gro product is much the same as we mentioned in our Seed Starting Mix article -their blend of plant food emphasizes vegetative growth and strong flowering, without the nutrients for fruit or food production. We have seen numerous gardeners with tomato plants growing lush, dark green leaves and covered in flowers but not producing a single tomato, or very few.

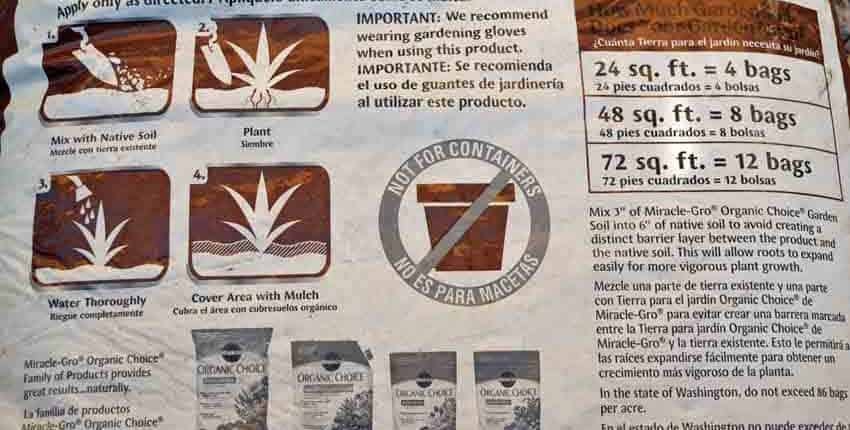

Looking at the back of the bag, we were surprised to see this product was not recommended for container gardening. It is also interesting to see the warning to wear gloves when using Organic Choice.

It’s labeled as “garden soil” on the front, but on the back the instructions say to mix 3″ of Organic Choice with 6″ of native soil, mix well to avoid a stratified layer, then plant. These instructions combined with the not for containers seems to indicate this is not a full potting soil and more of a soil amendment or fertilizer.

The ingredients listing says it is formulated with organic materials but doesn’t specify if “organic” means organic as in containing carbon, or organic as in certified organic.

It has much the same ingredients – forest products, compost, composted manure and pasteurized poultry litter. In addition it lists peat humus and sphagnum peat moss which are more commonly associated with seed starting mixes than potting soils.

The ingredients do vary regionally, which they do specify.

We searched the OMRI listing to see if this, or any, Miracle-Gro product was listed and found this is OMRI listed, along with several other products. This is somewhat surprising, as most other manufacturers proudly display the OMRI listing label. Another interesting detail is this has no restrictions, unlike Kellogg’s Amend. It is listed under fertilizer and soil amendments, which makes more sense of the instructions to mix with native soil.

On opening the bag we noticed it was moist with a dark brown, rich earth color. There was woody material present, but seemed a bit more integrated and had an earthy, soil based aroma. There was no indication of partially composted manure or off odors.

It didn’t have any mold indication and a handful of the soil had more of a substance to the texture, while still being light and fluffy. There were smaller or finer components to the mixture. There was less of a dark residue on the fingers after handling a handful for inspection.

Closer inspection shows the more even distribution of size, along with the dark brown or earthy color. This seemed to be closer to a replacement soil but with enough lightness to allow good root development.

Square Foot Potting Soil

The next bag was Garden Time Square Foot Garden Soil from Gro-Well Brands. They are local to us, being based in Tempe, AZ. This was bought at Lowe’s and we’ve seen it at Home Depot also, and have seen garden forum threads where it is possible to special order it online in different quantities. We also saw it at our local True Value Hardware store in the garden aisle, with a different design bag – so it is probably also available in independent garden centers as well.

We have used this particular mix for a few years now with good results. We primarily use it as a seed starting mix and transplanting medium, but have experimented with it as a complete soil – like the bag’s labeling says – and have been pleased with the results.

Having said that, it isn’t perfect either and makes many of the same claims as the other brands. The “Natural & Organic” label is prominent on the bag, even though this is not OMRI listed. Some of the other claims are “Proven Formula for Optimum Growth” and “Great for Vegetables”. It does say “ready to use” and doesn’t need mixing with native soils, something that might be helpful for a container gardener with a small patio or apartment balcony.

Square Foot Potting Soil Ingredients

The ingredients are compost, peat moss, coconut coir, vermiculite, bloodmeal, bone meal, kelp meal, cottonseed meal, alfalfa meal and worm castings. The peat moss, coir and vermiculite are classic seed starting mix ingredients, with the compost, different meals and worm castings adding nutrients to the soil for the plants growth and health. We use this as both a seed starting mix and potting soil or transplant soil because of the nutrients, which are lacking in straight seed starting mixes.

The same concern we voiced above at the vagueness of what is in the compost is valid here as well. In reading around a bit, I haven’t come across Gro-Well Brands using bio-solids in their compost, which is good news. On the other hand, that doesn’t mean the compost is organically sourced and not feedlot manure, but it’s a step in the right direction.

The more extensive list of ingredients give this some substance in nutrition so it can be used as a transplanting medium, a potting soil or as a complete standalone soil.

As another plus, we’ve not experienced seedlings dying when transplanted into this mix, nor have our customers said anything.

On opening the bag, the soil is slightly moist with a very dark, almost black color. It had almost no odor and felt light in weight but with some substance. This makes sense with the compost being 30 – 40% and much of the rest made up of lighter weight seed starting ingredients that have no odor of their own. The shiny vermiculite specks are easy to see and the texture is fairly even without lots of larger, identifiable chunks of wood.

A handful of the soil showed more of the smaller size particles making up the mix with an even and light feel to it. There was a trace of black residue on the fingers after a handful for inspection.

Square Foot Potting Soil

A closer inspection shows the darker color, with the specks of vermiculite showing through.

Garden Time Potting Soil

The last bag was also from Gro-Well Brands – Garden Time Potting Soil. This was also bought from Lowe’s, and is available in big box stores. It may be regionally available in independent garden centers with a different bag.

The same technique of word use – “Natural & Organic” was in play, but the other trigger words were missing. This is advertised as an all-purpose potting soil for indoor and outdoor use in containers and garden beds, as well as for transplanting.

Like the Square Foot Gardening soil, this is not OMRI listed.

Garden Time Potting Soil Ingredients

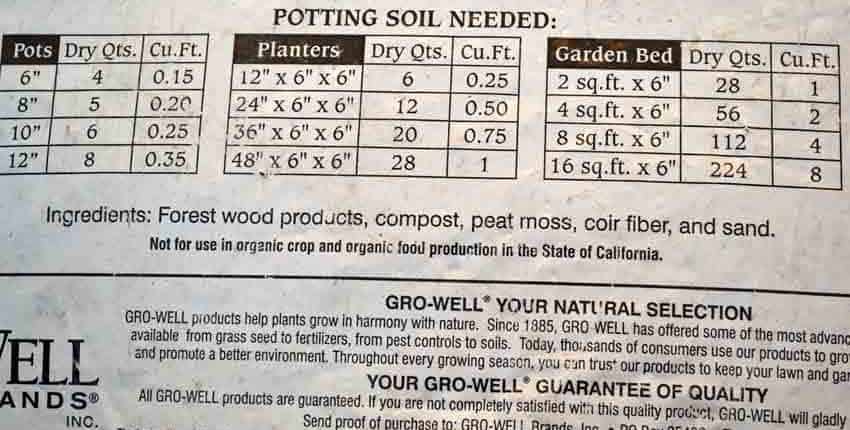

The ingredients are different, with fewer of the seed starting ingredients and less of the nutrient amendments. It does have peat moss and coconut coir fiber, common in seed starting mixes, but is without the perlite and such.

The standard forest wood products are there, as well as the compost listing again. What we found interesting is the addition of sand as the last ingredient.

Garden Time Potting Soil Closeup

When opening the bag we noticed this mix had a more woody aroma and was less earthy. It was also the driest of the mixes, leaving almost no residue on the hand after sifting through a handful of mix. It wasn’t dry, just much less moist than the other mixes. It had more substance and weight to the mix, probably as a result of the sand. This mix looked, smelled and felt the woodiest of the ones we inspected. It had no odor of compost or manure at all, only slightly of decomposed wood.

One thing we immediately noticed with a handful of soil is the white specks in the mix. In looking closely at them, they look much like perlite even though there is none listed on the ingredients. This could be an older bag with a new mix formulation, or a mistake in adding perlite to this mix. The perlite isn’t a negative, but the fact it isn’t listed in the ingredients makes us wonder a bit.

Even with this, the mix looks like it would be good as an amendment to loosen up native soils. The overly woody composition would be beneficial as it decomposed more, but might not add much to this season’s growth.

Garden Time Potting Soil Closeup

A closer look shows the woody texture and color with the white specks of what looks to be perlite throughout.

Potting Soil Cost Chart

In looking at the related costs, a couple of things stand out. The two best-looking soil mixes are also the most expensive – Miracle-Gro and the Square Foot Gardening Soil. They are also the smallest size bags. When adding in the positive benefits of an OMRI listing, the Miracle-Gro becomes the initial winner – something that surprised us.

In making a recommendation, an OMRI listing helps to assure a home gardener that the materials and ingredients used are of better quality and higher nutrient content than a non-listed mix. With that said, we would not recommend avoiding mixes which aren’t listed if you can be sure the ingredients meet reasonable standards. For example, compost from a neighborhood friend’s horses won’t be able to be OMRI listed, but would probably be excellent compost if the horses are fed well and wholesomely. The same would go for a grass-fed farmer in your area, who doesn’t feed growth hormones or regular antibiotics.

From this list, our two choices are the Miracle-Gro Organic Choice Garden Soil and the Square Foot Gardening Soil, with the others being a distant second choice if the first two weren’t available. This is conditional upon our testing some seedlings in each of these to see if they can actually support healthy seedling growth, but that will be another article!

For you, the best choice depends on what is available in your area, the amount of potting soil needed and what you can afford. Some gardeners, like ourselves, much prefer to make our own compost with multiple amendments to create a complex and wonderfully fertile soil amendment, while others simply don’t have the space or availability of materials. Some better options include creating a composting system as part of a community garden, or partnering with a friend or neighbor who has the space and is willing to boost their garden’s fertility. You might offer to do the work in setting up and maintaining the compost in return for some of the finished product for your garden.

Now you’ve got an overview of what to look for and be aware of when shopping for potting mixes, what are your thoughts and experiences? Do you have a dependable “go-to” potting mix you’ve used and loved for years? Or, do you have a tried and true recipe for mixing up your own potting soil that has never let you down? Please share!

Beneficial Soil Organisms – the Team Players

A Universe in Your Hand

In a handful of soil from your garden, you hold potentially billions of different living organisms hard at work making your soil a better place for your plants to live. Most of these team players are microscopic – too small to see with the eye, but a few are large enough to observe. Bacteria, fungi, mycorrhizae, protozoa and possibly algae are on the microscopic side while earthworms, pillbugs, arthropods and some nematodes are big enough to see in your hand.

We pay lots of attention to improving soil, for good reason. Healthy, fertile soil grows stronger, healthier, more productive plants while reducing insect and disease damages. You see and taste the difference in richer, brighter colors and sweeter or more flavorful vegetables and fruits.

Most attention focuses on the structure and chemistry of the soil – is the soil made up of sand, loam, clay or some mixture? The chemistry shows what nutrients are present and in what amounts. This is the common approach but leaves out one of the biggest components of soil improvement – the biological community.

It’s easy to overlook them because they can’t easily be measured – like determining soil structure or reading a soil analysis for nutrient deficiency.

There’s a saying among soil consultants that,”You must build a house for the biology.” That means that soil structure and chemistry must be aligned before the beneficial organisms can fully go to work. It also recognizes the critical but often overlooked role they play. Beneficial soil organisms release tied up nutrients in the soil and move them into the reach of plant roots, improve soil structure and increase nutrient retention, among many other things.

Now that you understand a bit more about them, let’s introduce you to your team!

The Big Boys

Starting with the larger, more visible players-

Earthworms – An acre of good garden soil can have between 2 and 3 million of these black gold producing workers, constantly processing organic matter into readily available nutrients your plants absolutely love.

That means each square foot of good soil in your garden can have up to 45 – 70 earthworms. You won’t be able to see all of them, as they can range a few feet deep.

Arthropods – are ants, mites, and springtails who voracious shred decomposing plant leaves, stems, and mulch. They do the heavy lifting, getting the plant organic matter into bite-sized pieces for the smaller team members.

Pillbugs– are land-based crustaceans, distant cousins to lobsters, crabs, and shrimp. They are scavengers, mainly feeding on moist, decaying plant materials – very useful in shredding dead plant matter so it can be fully decomposed.

If you see these guys in your handful of soil or in your garden, you are doing several things right. They won’t stick around in dead soil with little or no organic matter, or in soils that are heavily contaminated with pesticides.

The Little Guys

Now, on to the smaller and less visible players that are no less important –

Fungi – More common in woodland soils or in areas where woodchips have been laid down. They can appear as mushrooms with stems and caps – especially after a rain – but are more often seen as a whitish growth on moist and decomposing parts of the woody material. They send out hyphae or long, thin strands to decompose organic materials, transport nutrients, and improve soil structure while stabilizing it.

Protozoa – Single-celled animals that are always busily feeding on bacteria, soluble organic matter, and sometimes fungi. As the feed, they release nitrogen that is used by plant roots and other players on the team.

Actinomycetes – (pronounced act-in-o-my-seetees), are special beneficial bacteria that are responsible for the rich, earthy smell of freshly turned soil. Their specialty is digesting the high carbon cellulose in wood and the chitin of shed pillbug shells and insect bodies.

Beneficial bacteria – These microorganisms are more common in the nutrient-rich garden soils, forming associations with annual vegetables and grasses.

Beneficial nematodes – Not all nematodes are destructive, and these guys search out, infect, and kill targeted destructive insects. Different nematode species attack different pests.

Mycorrhizae – A very specialized fungi that bond with the tiny, hair-like roots of plants in a mutually beneficial relationship. The fungi send out hyphae into the soil to bring back specific nutrients needed by the plant, in return for a sugar-based plant sap that feeds the mycorrhizae. In essence, they feed each other what they can’t get for themselves. Mycorrhizae can only survive on living plant roots, and about 95% of our garden plants depend on their fungi friends to thrive.

Help Your Team Out

Now that you’ve met the team working tirelessly for you in the garden, help them out with making sure they’ve got food, water, and shelter – which compost provides almost everything for them!

When you hear someone talk about “beneficial soil organisms“, you will know exactly what they mean!

A Garden’s Beauty

If we are peaceful, if we are happy, we can blossom like a flower, and everyone in our family, our entire society, will benefit from our peace.

Life is filled with suffering, but it is also filled with many wonders, like the blue sky, the sunshine, the eyes of a baby.

To suffer is not enough.

We must also be in touch with the wonders of life. They are within us and around us, everywhere, any time.

– Thich Nhat Hanh

The glory of gardening: hands in the dirt, head in the sun, heart with nature.

To nurture a garden is to feed not just the body, but the soul.

– Alfred Austin

Gardening simply does not allow one to be mentally old, because too many hopes and dreams are yet to be realized.

– Allan Armitage

A garden is a grand teacher.

It teaches patience and careful watchfulness; it teaches industry and thrift; above all it teaches entire trust.

– Gertrude Jekyll

Everything that slows us down and forces patience, everything that sets us back into the slow circles of nature, is a help.

Gardening is an instrument of grace.

– May Sarton

Eden is that old-fashioned house

we dwell in everyday

without suspecting our abode

until we drive away.

– Emily Dickinson

He who plants a garden plants happiness.

If you want to be happy for a lifetime, plant a garden.

Chinese proverb

We have the world to live in on the condition that we will take good care of it.

And to take good care of it, we have to know it.

And to know it and to be willing to take care of it, we have to love it.

– Wendell Berry

The single greatest lesson the garden teaches is that our relationship to the planet need not be zero-sum,

and that as long as the sun still shines and people still can plan and plant, think and do,

we can, if we bother to try, find ways to provide for ourselves without diminishing the world.

– Michael Pollan

A society grows great when old men plant trees whose shade they know they shall never sit in.

– Greek proverb

The greatest fine art of the future will be the making of a comfortable living from a small piece of land.

– Abraham Lincoln

I like gardening – it’s a place where I find myself when I need to lose myself.

– Alice Sebold

But always, to her, red and green cabbages were to be jade and burgundy, chrysoprase and prophyry.

Life has no weapons against a woman like that.

– Edna Ferber

We are exploring together.

We are cultivating a garden together, backs to the sun.

The question is a hoe in our hands and we are digging beneath the hard and crusty surface to the rich humus of our lives.

– Parker J. Palmer

Plants want to grow; they are on your side as long as you are reasonably sensible.

– Anne Wareham

You can spend your whole life traveling around the world searching for the Garden of Eden, or you can create it in your backyard.

– Khang Kijarro Nguyen

I don’t want to return to the world outside these Gardens.

All I want is to notice the dew on a leaf.

The holy busyness of worms in the soil.

– Tor Udall

The garden is a kind of sanctuary.

– John Berger

I’d love to see a new form of social security … everyone taught how to grow their own; fruit and nut trees planted along every street, parks planted out to edibles, every high rise with a roof garden, every school with at least one fruit tree for every kid enrolled.

– Jackie French

These photos are the result of a leisurely, late afternoon spent wandering through the Denver Botanical Garden in early September.

Handmade Organic Soap

How We Clean Up After a Hard Day’s Work

Many of you know we are avid gardeners and own an heirloom seed company, but you may not know we also have a small farm. Gardening or working with our horses, ducks, and pigs always leaves our hands and body dirty.

We’ve searched for a good, all around soap, but it didn’t seem to exist. All of the bars we tried – and we tried a bunch – either cleaned well while stripping all of the moisture from our hands or left an unsettling film after rinsing. Almost none lasted very long and we had just about given up hope of a non-chemical, non-commercial soap we could use and really enjoy.

Researching what goes into soap opened our eyes – especially commonly used ingredients and processes used to make it. We began to understand why most soaps irritated our skin, didn’t clean well or melted too quickly.

The more we learned, the more we knew we wanted a natural and organic soap – something made entirely from plant-based, unrefined ingredients.

When we found and tried this particular soap, we knew our search was a success. We use and love this soap daily, so it made sense to offer it to our customers!

Just like our seeds, we contract with a small family company to produce the absolute best soap possible. Join us as we explore what goes into a great bar of soap!

Unscented Soap

What Makes a Great Bar of Soap?

A bar of soap appears simple sitting in your hand, but it must balance and maximize its best qualities – creamy fluffy lather that cleans while moisturizing, feels good and lasts well – all in one bar.

This takes work – research, experimenting, and testing – to accomplish. A perfect bar soap is a result of carefully choosing and balancing the various ingredients to boost the bar’s hardness, lather quality, cleaning, and moisturizing ability. For example – moisturizing ingredients don’t contribute much to lather quality, and what makes great lather often dries our skin out.

All soap is made through a chemical reaction where part of an oil molecule attaches to a sodium ion from sodium hydroxide, commonly called lye. This is called saponification.

A properly produced soap consumes all of the lye during the saponification process, eliminating any chance of skin irritation. Superfatting assures that all lye is consumed. This process retains extra skin-nourishing oils in the finished soap. Superfatting won’t make your skin oily, it helps it to maintain natural moisture levels.

Lemongrass Tea Soap

Can Soap be Certified Organic?

The USDA’s National Organic Program (NOP) sets the standard for organic production. Soap falls under the “Made with Organic” section – Products made from a minimum of 70% organic content up to 95%. The USDA has set 70% as the minimum percentage a product can have and still use “organic” in its labels and marketing.

So, what does this mean for you?

Organic certification guarantees there are no synthetic fragrances, colors, or preservatives in the soap, as well as that all the oils and herbs were grown and processed according to organic standards (no pesticides, no radiation, and environmentally friendly methods).

To us, this means a soap whose ingredients are plant-based with no artificial substances such as synthetic fragrances, dyes, and preservatives. Our pure herbal soap is scented with essential oils and colored exclusively with organic herbs and plant extracts. 100% certified organic oils make up the soap base recipe.

We feel it’s worth the extra time and effort to meet organic standards and make truly organic products. Your skin will know the difference!

Gardener’s Hand Soap

Why Essential Oils are Better

Essential oils are concentrated plant extracts from the roots, bark, and plant leaves.

Fragrance oils are always synthetic, even though they have perfectly natural names and might contain natural ingredients.

Fragrances smell great initially but quickly overwhelm your nose once you get it home, then it’s not so nice or enjoyable.

Essential oils are less “pushy” up front but retain their appealing qualities throughout the life of the bar, never overwhelming your nose.

Peppermint Soap

How Organic Soaps Get Their Colors

Natural colors can be bright and lively, creating a beautiful bar of soap.

Some essential oils, like citrus oils, have their own color that can be just what certain soaps need.

The easiest way to add or control soap color is with herbs or clays. The desired colors are created near the end of the mixing process by adding herbs, clays or a combination.

Steeping herbs in oil create richer and more vivid colors.

Citrus Lavender Soap

Why Exotic Ingredients Aren’t Included

Don’t be fooled by trendy or exotic ingredients on a label. If you don’t start with a well-formulated base, exotic ingredients won’t produce the soap you’re looking for. For example – palm kernel oil can be a great enhancement, but it can’t fix a poor formulation. Specialty ingredients are most commonly used as advertising hooks or as recipe magic in the hopes of creating a great soap from a poor-quality base. Glamorous ingredients or celebrity endorsements don’t produce extraordinary soap.

Lavender Soap

Try the Most Natural Soap Available

There’s virtue in products as natural as your skin. There are also practical benefits to using essential oils in skincare products.

Read labels carefully. If you see any variation or combination of the words fragrance, fragrance oil, or natural fragrance, don’t be fooled. There’s nothing natural about them.

Purchasing our handmade, organic soap gives you much more than just a great soap that leaves your skin clean. You support our small company and our soapmaker.

They, in turn, support growers for the ingredients of your bar of soap – ethical, sustainable and environmentally friendly methods that increase the soils over time and improves the communities where they are grown.

It turns out that a simple bar of soap can do some real good for many people!

Shea Butter Heals Hands While Healing Lives

A Short history of Shea Butter

The Shea tree – botanical name Butyrospermum parkii or Vitellaria paradoxa – grows in the dry Savannah belt of West Africa, stretching from Senegal in the west to Sudan in the east.

It has been an irreplaceable natural cosmetic pharmaceutical for people in Western Africa for millennia. Over the past few decades, it has become increasingly important in the skincare industries.

Most Americans know Shea butter as a highly touted skin care ingredient in a variety of soaps, lotions, balms, and butters.

Few realize the Shea advertised in the majority of cosmetic products in the US is nothing more than another highly refined food grade oil churned out of an industrial plant, regarded as just another commodity.

Pure hand-crafted Grade A Shea butter is a world apart from this!

Real Shea butter is wild-crafted, hand harvested and handmade

Shea butter has been known as “women’s gold”for centuries for its light golden color but also because it’s historically been the work of women to harvest and produce Shea butter.

Millions of women across Western Africamake their own incomes and are improving their lives producing traditional Shea butter.

Women-owned and organized cooperatives harvest the ripe Shea fruits from wild growing Shea tree forests. Fermentation removes the fruit, then the nuts are sun-dried, crushed and lightly roasted, concentrating the Shea butter.

Finely ground Shea nut powder is mixed with warm water and constantly stirred until it thickens. Warm, liquid Shea oil is collected from the surface, then strained and slowly cooled to form Shea butter. After packaging it is sold at the local markets or exported.

It takes approximately 44 pounds of fresh Shea fruit to produce 3.3 pounds of pure Shea butter.

Shea Tree Flowers

What is Fair Trade?

Fair Trade certification is awarded after meeting certain standards, similar to organic certification. There are benefits and challenges, just like with the Certified Organic label.

This adds to the overall cost, but there are benefits most consumers never know about.

Beyond Fair Trade – Partnering with the Producers

We – our supplier and ourselves – work as closely as possible with women’s cooperatives to keep the quality high, and also to pay them fairly.

Working directly with the cooperative and the Fair Trade organization, we eliminate as many profit-taking intermediate layers as possible while having a larger positive impact than we could by ourselves.

For example – currently, Shea nut harvesters earn 15 cents per pound and the women’s cooperative we work with want to pay the harvesters 25 cents per pound, only 10 cents more but a whopping 66% pay raise.

However, it isn’t as simple as just paying them more.

Regional and local politics, combined with existing laws, are making it difficult to simply give the harvesters a raise, so the Fair Trade organization is working with our women’s cooperative to change this.

A Shea nut harvester might earn $60/month, which allows her to live in a straw-thatched hut with no power in a communal village and walk up to a half mile for water at a common, communal well.

A 10 cent per pound pay raise will give her and her family a solid walled, roofed apartment with running water and a community generator for electricity.

Shea processors – who actually turn the nuts into Shea butter – make about $175/month, and the women’s cooperative is working to raise that to $225/month.

The additional income almost always paysfor schooling, whether it is getting all of their children into schools, or enrolling them in full-time private charter schools with a full curriculum.

The Virtuous Cycle

Buying your Shea butter from a company engaged in direct, positive impact on the local producers gives your purchases a much larger effect simply because much more of each dollar makes it to those producers. This is exactly how one person makes a difference!

The standard commodity approach to Shea butter has so many layers – traders, intermediaries, transportation expenses, and investors – between the Shea butter producers and the US consumer that not even one penny of each dollar spent on a commercial Shea-labeled product reaches those in Africa.

According to The New York Times, a survey of a Burkina Faso village by USAID in 2010 found that every $1,000 of Shea nuts sold generated an additional $1,580 in economic benefits, such as reinvestments in other trades for the village. Shea butter exports from West Africa bring in between $90 million and $200 million a year, according to the article.

Much like the disproportionately large positive effects of spending your money at a Farmer’s Market instead of the grocery store, purchasing pure, unrefined Grade A Shea butter from a dedicated company partnering with a small producer ensures a better life for those making it.

Ethically sourced Shea butter heals our hands and skin while healing the lives and villages who make it.

Ethel M Botanical Cactus Garden

Chocolates with a Side of Cactus Garden?

Las Vegas is often thought of for its glittering lights and heady atmosphere of the Strip. That’s exactly what lost me about its appeal, even though Cindy and I had visited numerous times for gardening trade shows along with a few personal trips.

A few times down the Strip and we started looking for something other than the glitz and glam.

We found Ethel M and its unique botanical garden that focuses on cacti and species from the Southwest US and other countries with a similar climate. Cindy searched for something interesting and relaxing after the bustle and noise of a garden trade show and came across this treasure.

Ethel M chocolate factory – as in Ethel Mars – is part of the Mars family with the factory store housing the botanic garden in Henderson, NV just a few minutes south of Las Vegas. The self-paced tour runs along the dedicated viewing aisle next to the factory floor, then we sampled some excellent chocolates and had an unexpectedly good cup of espresso. Afterwards, we were ready for some botanic garden exploration.

We visited during an afternoon in early May with temperatures hovering around 100°F – not the best light for photos and I had left my usual camera at home, not anticipating a photo opportunity. Armed with my trusty cell phone and a couple of bottles of water, we ventured out into the garden, not quite knowing what to expect.

Impressive beauty and peace

Bee in Prickly Pear Flower – Ethel M Botanic Garden

Over 300 species of cactus, desert-adapted ornamentals and succulents are spread over 10 acres. Artfully arranged in intriguing and enticing groupings, the pull from flowers to cactus to trees made us feel something like the numerous bees and hummingbirds we saw.

Prickly Pear Detail – Ethel M Botanic Garden

The peace and quiet after the noise and crush of crowds was a very welcome respite. Plantings are slightly elevated, inviting an easy look into the details of the life growing there.

These early prickly pear cactus buds are mathematically gorgeous in their symmetry, blushing with an indication of their rich colors to come.

Flower Closeup – Ethel M Botanic Garden

Abundantly blooming flowers were generously spread across the entire garden, with some reaching out with colors and others beckoning with aromas from 20 or 30 feet away.

We weren’t paying attention to the nameplates or descriptions of the flowers or plants but focused instead on the experiences of colors, textures, and aromas drawing us in.

Blooms – Ethel M Botanic Garden

Some plants and their flowers seemed as though they would be right at home as an attraction on the Strip, such as this one!

Given how close the I-515 freeway is the quiet and peace were impressive. The garden had a number of people in it but it never felt crowded.

Flower Blooms – Ethel M Botanic Garden

This flower group had a sweet, perfumed aroma drawing us in from two plantings over. The trumpet-shaped flowers had dozens of small flying insects and bees attending them.

Flower Blooms – Ethel M Botanic Garden

Colors ranged from white to purple with a lot of orange and reds represented. It was high season for blooms as very few plants lacked flowers.

Ethel M Botanic Garden

The surrounding city disappeared from certain viewpoints, giving the illusion of a private estate garden or an undiscovered, undeveloped patch of exotic forest somehow forgotten.

We came away relaxed and refreshed, completely surprised by how wonderfully juxtaposed the experience was from the busy city just down the street. The rest of the day was just as enjoyable, and we realized that this was the best trip to Las Vegas we remembered, simply because of a visit to a garden.

We’ve learned to search a bit deeper for those unexpected garden treats like this!

Cool Season Vegetables to Love

Cool Season Vegetables for Your Garden

Gardeners are sometimes baffled when thinking about a cool season garden – either Fall and Winter or early Spring. We’ve put together this quick checklist to help you see the abundance that can be grown both before and after the traditional Summer garden.

Spend some time browsing these and making notes on what you like to eat and what varieties do well in what dishes you like to cook – pretty soon you’ll have a mouth-watering list to plant!

Which cover crop mix is best for me?

Soil Builder vs Garden Cover Up Mix – which is best for your garden?

Both of our cover crop mixes give you multiple benefits in the soil and above it. You can’t go wrong with either one. The Garden Cover Up mix is a general use cover crop, while the Soil Builder mix is more specific toward improving the overall condition of your soil.

Cover crops improve soil in a number of ways. They protect against erosion while increasing organic matter and catch nutrients before they can leach out of the soil. Legumes add nitrogen to the soil. Their roots help unlock nutrients, converting them to more available forms. Cover crops provide habitat or food source for important soil organisms, break up compacted soil layers, help dry out wet soils and maintain soil moisture in arid climates.

Let’s look at how cover crops work overall, then we’ll see the differences of each mix.

Most cover crop mixes are legumes and grains or grasses. Each one has a different benefit to the soil. Legumes include alfalfa, clover, peas, beans, lentils, soybeans and peanuts. Well-known grains are wheat, rye, barley and oats which are used as grasses for animal forage.

Crimson Clover

Legumes

Legumes help reduce or prevent erosion, produce biomass, suppress weeds and add organic matter to the soil. They also attract beneficial insects, but are most well-known for fixing nitrogen from the air into the soil in a plant-friendly form. They are generally lower in carbon and higher in nitrogen than grasses, so they break down faster releasing their nutrients sooner. Weed control may not last as long as an equivalent amount of grass residue. Legumes do not increase soil organic matter as much as grains or grasses. Their ground cover makes for good weed control, as well as benefiting other cover crops.

Rye Cover Crop

Grains or grasses

Grain or grass cover crops help retain nutrients–especially nitrogen–left over from a previous crop, reduce or prevent erosion and suppress weeds. They produce large amounts of mulch residue and add organic matter above and below the soil, reducing erosion and suppressing weeds. They are higher in carbon than legumes, breaking down slower resulting in longer-lasting mulch residue. This releases the nutrients over a longer time, complementing the faster-acting release of the legumes.

This pretty well describes what our Garden Cover Up mix does, as it is made up of 70% legumes and 30% grasses.

Our Soil Builder mix takes this approach a couple of steps further in the soil improvement direction with the addition of several varieties known for their benefits to the soil structure, micro-organisms or overall fertility.

For example, the mung bean is a legume used for nitrogen fixation and improving the mycorrhizal populations, which increase the amount of nutrients available to each plant through its roots.

Spring Sunflower

Sunflowers are renowned for their prolific root systems and ability to soak up residual nutrients out of reach for other commonly used covers or crops. The bright colors attract pollinators and beneficials such as bees, damsel bugs, lacewings, hoverflies, minute pirate bugs, and non-stinging parasitic wasps.

Safflower has an exceptionally deep taproot reaching down 8-10 feet, breaking up hard pans, encouraging water and air movement into the soil and scavenging nutrients from depths unreachable to most crops. It does all of this while being resistant to all root lesion nematodes. Gardeners growing safflower usually see low pest pressure and an increase in beneficials such as spiders, ladybugs and lacewings.

Now you see why you can’t go wrong in choosing one of our cover crop mixes! Both greatly increase the health and fertility of the soil, along with above-ground improvements in a short time. Even if you only have a month, the Garden Cover Up mix will impress you for the next planting season.

For a general approach with soils that need a boost but are still producing well, the Garden Cover Up mix is the best choice. Our Soil Builder mix is for rejuvenating a dormant bed or giving some intensive care to a soil that has struggled lately. Both will give you a serious head start in establishing a new growing area, whether it is for trees, shrubs, flowers, herbs or vegetables.

Grow Lettuce in Summer

Grow Your Lettuce Longer in Warm Weather

With a little knowledge and a tiny bit of preparation, you can grow lettuce throughout the summer without bolting. Imagine serving your own fresh-harvested, garden-grown lettuce throughout the summer!

First, some knowledge

Lettuce is a cool-season vegetable, meaning it grows best in temperatures around 60 – 65°F. Once temperatures rise above 80°F, lettuce will normally start to “bolt” or stop leaf production and send up a stalk to flower and produce seed. The leaves become bitter at this stage.

This is because the mainstay of our beloved salads is not a North American native, but an ancient part of our dinner table. Belonging to the daisy family, lettuce was first grown by Egyptians around 4,700 years ago. They cultivated lettuce from a weed used only for its oil-rich seeds to a valued food with succulent leaves that nourished both the mind and libido. Images in tombs of lettuce being used in religious ceremonies show its prominent place in Egyptian culture.

The earliest domesticated form resembled a large head of Romaine lettuce, which was passed to the Greeks and then the Romans. Around 50 AD, Roman agriculturalist Columella described several lettuce cultivars, some of which are recognizable as ancestors to our current favorites. Even today, Romaine types and loose-leaf lettuces tolerate heat better than tighter heading lettuces like Iceberg.

Three factors to growing lettuce in summer

The temperatures you are concerned about are both air and soil, as a lettuce plant (or any garden plant for that matter) tolerates a higher air temperature if the soil around its roots is cool and moist. Ensuring a cool and damp soil gives you more air temperature leeway. Because lettuce has wide and shallow roots, a drip system on a timer teamed up with a thick mulch keeps it happier in warm weather.

Shade is the third part to keeping lettuce growing vigorously later into warm weather. Reducing sun exposure lowers the heat to the leaves, but also to the soil and roots – creating a combined benefit. Deep shade isn’t good, but a systemallowing sun during the morning while sheltering the plants in the afternoon keeps your salad machines going much longer than you thought possible.

One last bit of knowledge. Most lettuce seeds become dormant (won’t germinate) as temperatures rise above 80°F, a condition called”thermo-inhibition”. This trait is a carryover from wild lettuce in the Mediterranean Middle East, where summers are hot with little moisture. If the lettuce seeds sprouted under these conditions, they would soon die out and the species would go extinct.

Thanks to research, there are some easy techniques to germinate lettuce seeds in warm weather – our article Improve Lettuce Seed Germination shows you how. Now you’ll be able to start lettuce when no one else can!

Here’s how to grow lettuce in summer

The three most effective elements in keeping your lettuce producing during warm weather are a drip system on a timer, a good bed of mulch and shade. Let’s look at each one and how they help.

Lettuce growing with mulch, shade & drip system

A drip system on a timer maintains moisture levels much more evenly than hand watering, and the timer can be set for how much and how often water is needed. Checking the soil moisture levels is easy – just push your finger into the soil up to the second knuckle. If the soil feels moist and spongy the moisture is perfect for lettuce. Adjust the number and length of watering each time up or down to maintain this level. From experience, we usually start the timer once a day for 10 minutes in the spring and go to 2 and sometimes 3 times a day for 10 minutes during the heat of the summer. As the weather cools down, we decrease the amount of water accordingly.

A thick bed of mulch reduces moisture loss at the surface of the soil from heat and breezes. Here in central Arizona, it’s not uncommon to have a 15-mph breeze with 90°F+ with 5 – 10% humidity levels. Basically, we garden in a giant hair-dryer!

We use two inches of wood chip mulch, but straw also works well and some gardeners have good success with well-aged compost. With mulch, the soil moisture levels are at the top of the soil where it meets the mulch. Without it, the moisture doesn’t appear until you’ve dug down at least two inches, with three inches having the same amount of moisture as the surface does with mulch. Another benefit of wood chip mulch is it provides needed nutrients to the soil and encourages earthworms and other beneficial soil life as it decomposes. The beds where we’ve put wood chips down have three times the amount of earthworm activity as those that have only compost or nothing at all.

The third element is shade, which might seem daunting but is surprisingly simple to provide. Shade can be from various sources – a living trellis of cucamelon, vine peach or Malabar spinach; a row of tall sunflowers on thewest side of the bed; a container garden on the east side of the house or garage to capture afternoon shade, or a shade cloth structure on the west side of the bed or over a container or raised bed. Trees can also give partial shade – grow on the east side to take advantage of shade during the hotter, more stressful afternoons.

Real world examples

Here are two examples showing that it does:

The first example is a study conducted by Kansas City area growers in cooperation with Kansas State University and the Organic Farming Research Foundation.

The second example is a two-season grow-out test by the Sacramento County Master Gardeners at their Fair Oaks Horticulture Center during the summers of 2015 and 2016.

Easy shade for your garden beds

Here’s a quick and easy way to shade any container, raised bed or row in your garden:

Simple lettuce shade structure

Use 1/2 inch PVC pipe from any hardware store. 1/2 inch is the least expensive and easiest to work with for this use.

Shade structure detail

Using PVC elbows, simply insert the tubing into the elbow and push the uprights into the soil at the edge of the planter or raised bed. No glue needed, so they can be taken down and re-used next season.

Planter with shade system

We used some leftover shade cloth from another project and cable ties to secure the shade cloth to the PVC tubing.

Shade cloth canopy

The front of the shade canopy is left loose so we can harvest easily.

Lettuce shade detail

The right half of the lettuce is shaded, with the left half getting shade as the day progresses.

Now you have the tools and knowledge, so plan on successfully growing lettuce after everyone else has given up this season! As your accomplishments are recognized and compliments roll your way – make sure to share your tools and spread the success.

Update – Three Weeks Later

Lettuce after 3 weeks of heat

Our lettuce looks amazing, considering we’ve had continuous temperatures above 95°F for the past 13 days and above 100°F for the past 9 days. The Sweet & Spicy Mix hasn’t slowed down and is robust, crunchy, and still sweet with no bitter flavors. The growth is easy to see, comparing to the above photos.

Lettuce after 3 weeks of heat – detail of leaves

Looking closer, it isn’t perfect. There are some small holes and some of the leaf edges are a little toasty, but these conditions are so far outside of lettuce comfort zone, it’s like growing on Mars!

References

Homegrown Sprouts Safety

Are homegrown sprouts safe?

We’ve greatly enjoyed our own homegrown sprouts for the past several years. There’s just something about their fresh taste and crispy crunch that can be enjoyed any time of year, no matter the weather.

As with all our seeds, we make sure we know who our growers are and where our seeds come from. This is even more important with seeds used for sprouting as they are eaten directly as a food.

We chose our sprouting seeds supplier because of their commitment to the safest and healthiest seeds possible. They showed us their safety standards and testing protocols and we want to share them with you.

Growing your own sprouts at home is much safer than buying them off the shelf at a supermarket, and we’ll show you why.

Sprouts are healthy, nutritious and are rich in vitamins, minerals, proteins, enzymes, bioflavonoids, antioxidants, phytoestrogens, glucosinolates and other phytochemicals. They are an excellent alternative to meat, especially for vegetarians and vegans.

Fresh Homegrown Sprouts

Hazards of sprouts

There are two main hazards associated with sprouts – E. coli and Salmonella. Both of these terms are used a lot, but what do they really mean? What are they and where do they come from?

From the CDC website:

“Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria normally live in the intestines of people and animals. Most E. coli are harmless and actually are an important part of a healthy human intestinal tract. However, some E. coli are pathogenic, meaning they can cause illness, either diarrhea or illness outside of the intestinal tract. The types of E. coli that can cause diarrhea can be transmitted through contaminated water or food, or through contact with animals or persons.”

From the USDA website:

“Salmonella is an enteric bacterium, which means that it lives in the intestinal tracts of humans and other animals, including birds. Salmonella bacteria are usually transmitted to humans by eating foods contaminated with animal feces or foods that have been handled by infected food service workers who have practiced poor personal hygiene.”

How to be safe

The best and surest method of reducing the risk of sprout seeds carrying bacteria is making sure the seeds are never contaminated. This starts with an ethical grower using good agricultural practices and organic standards. The next step is conducting rigorous testing, both in-house and independently.

Mung Bean Sprouts

Sprouts seed testing

The testing done on our sprout seeds is different than any other testing protocols for food. There is no acceptable “percentage of contamination”, as is often the case with other foods. If any bacterial contamination is detected, testing is stopped and the entire lot is rejected – sometimes 40,000 pounds or more.

To ensure the sprouting seeds we offer are as safe as possible, our supplier extensively tests both the sprouting water and the seeds to verify if any bacteria is detectable after harvest. Our supplier and an independent lab both do multiple tests to safeguard our health safety.

As of early 2017, our supplier is the only company doing these extensive screening and testing protocols. The FDA is studying this protocol and has begun advocating its adoption by sprout companies for testing.

Initial Sprouts Screening Results

Screening includes inspecting the bags for any urine or feces contamination, any holes in the bags, insect larva or other contamination. Afterwards, the seed is carefully inspected with both a magnifying glass and microscope.

Each and every bag is screened – this particular lot had 860 bags, each one weighing 50 lbs. for a total of 43,000 lbs.

In-House Lab Spent Irrigation Water Contamination Test

A small sample of seed is taken from each bag and added to the overall lot sample. The entire sample is sprouted for 48 hours, increasing any potential bacteria level approximately 1,000,000 times over the starting amount, substantially increasing the probability of detection.

Next, the sprout runoff water is sampled and tested by the in-house lab. This is called “spent irrigation water”. A sample of the sprouts is crushed and tested for contamination also. These tests are done in accordance with government food safety and industry accepted protocols.

The lab tests for both Salmonella and E. coli 0157:H7 after 48 hours and again after 96 hours of culturing the irrigation water.

Both bacteria do most of their growth in the first 2 days or 48 hours. This is when the first test is performed, with the second test at 4 days or 96 hours. The second test catches any late developments that might be missed on the first.

Independent Lab Spent Irrigation Water Contamination Test

A separate, larger sample of spent irrigation water is sent to an independent lab for more extensive testing. The independent lab performs a more in-depth analysis on a wider range of pathogens than the in-house lab because of their higher level of equipment.

Notice that the independent lab tests for the top seven strains of E. coli, where the in-house lab tests for the most common one. The lab uses a food microbiology genetic detection system.

This is possible because the specific genes or DNA of the different strains of E. coli have been mapped, so they are specifically targeted during this testing. This gives better accuracy, repeatability, and confidence in the testing than any previous methods.

Independent Lab Sprouting Test

Next, the independent lab tests four pounds of randomly obtained sprouting seed from the shipment. Having an independent, third-party lab analyze the sprouting seeds gives an additional measure of confidence.

Storage Confirmation

Finally, the storage facility is inspected and documented. This ensures the cleanliness and food safety of how the seed is stored to avoid insect or rodent infestation or damage.

Homegrown sprout safety

In a home environment with only one person in contact with the sprouting seeds, cleanliness and food safety is much easier. Here are a few tips for sprouting safely:

Now you know the steps taken to ensure the highest quality sprouting seeds are available so you can enjoy the taste and nutrition of sprouts with peace of mind.

Spring Onions – When and How to Plant

Great Onions in Spring

Spring onions have been grown for a long time – Egyptians grew them along the Nile during the time of the Pharaohs. One of the easiest vegetables to grow, onions sometimes confuse home gardeners as to the best type for their garden.

Three forms of spring onions can be planted: seeds, transplants and bulbs (or sets):

We recommend using onion bulbs, which can be planted without worry of frost damage and have a higher success rate than transplants. Bulbs are perfect for the home gardener as they guarantee onions for use or storage within a few weeks after planting.

As a member of the allium family they are a natural pest repellant to most foraging animals in the home garden.

Red Wethersfield Onions

Day Length for Spring Growing

Spring onions are usually sorted by the amount of daylight hours they need to grow bulbs; these are known as day-neutral and long day onions. Day-neutral onions form good size bulbs with 12 – 14 hours of daylight, while long-day onions need 14 – 16 hours.

The map above shows the approximate latitudes where long-day onions need to be grown. Day-neutral onions will also grow well in the more northern states in spring and summer.

Day-neutral onions are usually sweeter and juicier than their long-day counterparts. Their higher sugar and water content make them best suited for cooking and immediate use instead of storage. They are best planted from early spring to mid-summer in northern states and early spring to late fall in southern ones.

Candy is our day-neutral onion, being adapted to a wide range of day-lengths from north Texas to Maine. 12 to 14 hours of daylight will produce a good bulb. These can be grown in Zones 5 to 9.

Long-day onions are just the opposite with lower sugar and water content but higher sulphur, making them best for storage and cooking. These are planted in early spring in mid to northern states for fall harvest.

Our long-day selections include Yellow Stuttgarter (in the header photo), White Ebenezer and Red Wethersfield onions. They do best with 14 to 16 hours of daylight to form a good-sized bulb and are typically grown in colder winter areas. Zone 6 and colder is a good rule.

Sweet Candy Onions

Planting and Growing Spring Onions

Spring onions prefer abundant sun and well-prepared, healthy soil with good drainage.

While onions will grow in nutrient poor soil, they won’t form good bulbs or taste as good. If possible, till in aged manure the fall before planting. Onions are heavy feeders and need constant nourishment to produce big bulbs. If needed, add a natural nitrogen source when planting, such as fish emulsion or aged compost.

Feed every few weeks with nitrogen rich fish emulsion to get good sized bulbs. Synthetic nitrogen fertilizer will grow larger bulbs at the expense of flavor. Stop fertilizing when the onion starts pushing the soil away and the bulbing process begins. Do not put the soil back around the onions; the bulb needs to emerge above the soil.

Onions have short roots and need about an inch of water per week, including rain water to avoid stress from lack of moisture. Mature bulb sizes will be smaller if they do not receive enough water. Raised beds and rows are good growing locations.

It is important to keep onion rows weed-free until they become well established. Mulching helps protect them from weeds competing for water, as well as preventing moisture loss from sun and wind.

Stuttgarter Onions

Harvesting Your Onions

Spring onions are ready for harvest when the bulb has grown large and the green tops begins to brown and fall off. The plant should be pulled at this point, but handle them carefully as they bruise easily, and bruised onions will rot in storage.

Onions need to be cured before storing. Cure them with their tops still attached, in a dry location with good air circulation – they can hang on a fence or over the railing on a porch to cure if there is no rain in the forecast. During curing the roots will shrivel and the tops will dry back sealing the onion and protect it from rot. After 7 – 10 days clip the tops and roots with shears, then store them in a cool, dry environment or use for cooking.

With a little experimenting and succession planting, you will find it easy enough to grow most of your own onions throughout the year. After tasting home-grown onions, you won’t want “store-bought” anymore!

Salsify – the Vegetable Oyster

An Ancient Vegetable

Salsify, also known as Oyster plant or vegetable oyster, was popular with the ancient Greeks who called it “the billy goat’s beard” for the silky filaments adorning the seed. The Romans increased it’s status, depicting it in frescoes in Pompeii. The famous Roman gourmet Apicius developed several recipes dedicated to Salsify and Pliny the Elder mentions it several times in his writings.

Europeans know the more common and darker scorzonera, meaning “black bark” in Italian. Salsify is regaining popularity with market and home gardeners for the delicately tasty roots and chicory flavored leaves.

Salsify Plant

This cold hardy biennial herb has a moderately thick taproot covered by a light brown skin. It has a purple flower, distinguishing itself from scorzonera by its black root and yellow flowers.

Edible Parts of the Plant

Salsify Root

The entire plant is edible when young and the root is eaten after maturing.

Young roots are eaten raw in salads, or are boiled, baked, and sautéed once mature. They are added to soups or are grated and made into cakes. The flower buds and flowers are added to salads or preserved by pickling. Young flower stalks are picked, cooked, dressed and eaten like asparagus. The seeds are sprouted and eaten like alfalfa sprouts for a refreshing and unique flavor addition.

Salsify Fritter

Cooked and puréed roots coated in egg batter and flour then pan or deep-fried to a crispy golden brown make Salsify fritters.

The Salsify root stores its carbohydrates as inulin instead of starch, which turns to fructose instead of glucose during digestion. This is ideal for diabetics as it reduces their glucose load. Most enjoy the flavor of the cooked roots over the raw.

Salsify Seedhead

Planting Seeds

Seeds are direct sown in early March to April then harvested in October. The slender, grass-like leaves normally grow to about 3 feet tall and one purple petalled flower per stalk. As the seeds mature, the flower heads turn into fluffy white puff-balls like dandelion heads and scatter on the wind.

Young Salsify Root

The root is ready for harvest in the fall when the leaves begin to die back. Flavor improves after a few frosts. Dig the roots out whole with a garden spade or fork to avoid breaking them. Only dig what you need at one time, because the roots are best fresh. Salsify will overwinter, tolerating hard frosts and even freezes.

Seed Testing and Preservation: A Behind the Scenes Look at Seed Testing Labs and the USDA

Stephen was invited to provide an article on seed quality for Acres USA’s January 2017 issue that focuses on seeds. This is the article that was published in that issue.

Better Seed for Everyone

Everyone wants higher quality seed – from the seed company, seed grower, breeder and home gardener to the production grower. Even people who do not garden or grow anything want better seed, though they may not realize it.

Education and quality seed is the focus of our company – Terroir Seeds. We make constant efforts to continue learning and educating our customers about how seeds get from the packet to their garden. We recently had the opportunity to visit several cutting-edge seed testing laboratories and the USDA National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation to learn even more about seed testing and preservation. We want to share an insider’s look into a side of the seed world that the average person may not know exists.

Let’s look at this need for higher quality seed from a different perspective.

Anyone who eats depends on seed of some sort for their daily food – from fruits and vegetables to grains, beans, rice and grasses for dairy and meat production. Seed is intimately tied into all these foods and their continued production. Without a continued, dedicated supply of consistently high quality seed there would be catastrophic consequences to our food supply.

Cotton, cotton blends, wool, linen, hemp and silk fabrics all come from seed. Cotton comes from a cotton seed, wool from a sheep eating grass and forage from seed, linen from plant stalks grown from seed, hemp from seed and silk from silkworms eating leaves that originated as a seed.

Even those who grow and cook nothing need better seed! They still eat and wear clothes.

Pepper with Purpose

Chile de Agua for sale at market

The Chile de Agua pepper from Oaxaca, Mexico is a prime example of how seed preservation works. A well-known chef specializing in the unique Mexican cuisine of Oaxaca needed this particular chile for several new dishes. This chile wasn’t available in the US, so we were contacted through friends to work on sourcing the seed.

We found two sources in the US of supposedly authentic Chile de Agua seed and another in Oaxaca, Mexico. After the Oaxacan seed arrived, and those from Seed Saver’s Exchange network and the USDA GRIN station in Griffin, GA we sent them to our grower for trials and observation. All three seed varieties were planted in isolation to prevent cross pollination.

Authentic Chile de Agua has unique visual characteristics, the most obvious being it grows upright or erect on the plants, not hanging down or pendant. Both seed samples from the US were pendant with an incorrect shape. Only the Oaxacan seed from Mexico was correct. We then pulled all the incorrect plants, keeping only the seed from the correct and proper chiles.

The next 3 seasons were spent replanting all the harvested seed from the year prior to build up our seed stock and grow a commercial amount sufficient to sell. This process took a total of four years to complete.

Creating High-Quality Seed

There are two major approaches to improving seed quality – seed testing and seed preservation. One verifies the current condition of the seed, while the other works to preserve previous generations for future study and use.

There are several different methods of seed testing, from genetic verification and identifying DNA variations to diseases to the more traditional germination and vigor testing.

Likewise, approaches to preserving the genetic resources of seed are varied – from a simple cool room to climate and humidity controls for extended storage to cryogenic freezing with liquid nitrogen.

Seed Testing

At its most basic, testing of seed simply verifies the seed’s characteristics right now. Whether testing for germination, vigor, disease screening, genetic markers or seed health, the results show what is present or absent today. Changing trends in important characteristics are identified by comparing with previous results.

Seed germination testing

This trend analysis is a perfect example of seed testing and preservation working together, as previous generations of seed can be pulled for further testing or grown out and bred to restore lost traits.

Modern seed testing labs perform a staggering array of tests and verifications on seed samples.

These three tests are critical for determining a seed’s performance in the field, and satisfy the US seed labeling law showing germination, physical purity and noxious weed percentages.

Seed health testing screens for seed-borne pathogens like bacteria, fungi, viruses and destructive nematodes. Seed for commercial agriculture and home gardens are often grown in foreign countries and shipped into the US, and vice versa. Seed health testing verifies the incoming or outgoing seed is free of pathogens that could wreak havoc.

Seed vigor test

Plant breeders use the healthiest seed stock possible that is free of any pathogens which would compromise breeding efforts. Agricultural researchers use tested pathogen-free seed to avoid skewing results or giving false indications from unforeseen disease interactions.

Hybrid seeds need to be tested for genetic purity, confirming their trueness to type and that the hybrid crossing is present in the majority of the seed sample. Traditional open pollinated breeders will use genetic purity testing to confirm there is no inadvertent mixing of genetic variations, verifying the purity of the parental lines.

It is common to test heirloom corn for GMO contamination – called adventitious presence testing. This test identifies any unwanted biotech traits in seed or grain lots. This is an extremely sensitive DNA based test, capable of detecting very low levels of unwanted traits in a sample – down to hundredths of a percent. This relatively expensive test demonstrates the absence of GMO contamination, an important quality aspect in the heirloom seed market.

Genetic fingerprinting, also called genotyping, identifies the genetic make-up of the seed genome, or full DNA sequence. Testing with two unique types of DNA markers gives more precision and information about the genetic diversity, relatedness and variability of the seed stock.

Computer graph of DNA testing

Fingerprinting verifies the seed variety and quality, while identifying desirable traits for seed breeders. This testing identifies 95% of the recurrent parent genetic makeup in only two generations of growing instead of five to seven with classic breeding, saving time and effort in grow-outs to verify the seed breeding. Genotyping also accelerates the discovery of superior traits by their unique markers in potential parent breeding seed stock.

The difference is how the breeding is verified, both before and after the exchange of pollen from one plant to another. The genetic markers identify positive traits that can be crossed and stabilized, and those markers show up after the cross and initial grow-outs to verify if the cross was successful. If it was successful, the grow-outs continue to stabilize and further refine the desired characteristics through selection and further testing. If it wasn’t successful, the seed breeder can try again without spending several years in grow-outs before being able to determine the breeding didn’t work like expected.

Seed Preservation

There are several different types of seed preservation, just as with seed testing. The foundational level is the home gardener, grower or gardening club selecting the best performing, best tasting open pollinated varieties to save seed from. Replanting these carefully selected seeds year upon year results in hyper-local adaptations to the micro-climates of soil, fertility, water, pH and multiple other conditions.

Many countries around the world have their own dedicated seed and genetic material preservation networks, such as Russia’s N.I.Vavilov Research Institute of Plant Industry. It is named for Nikolai Vavilov, a prominent Russian botanist and geneticist credited with identifying the genetic centers of origin for many of our cultivated food plants.

The Millennium Seed Bank Partnership is coordinated by the Kew Royal Botanic Garden near London, England and is the largest seed bank in the world, storing billions of seed samples and conduct research on different species. Australia has the PlantBank, a seed bank and research institute in Mount Annan, New South Wales, Australia.

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault on the Norwegian island of Spitzbergen is a non-governmental approach with donations from several countries and organizations. AVRDC – the World Vegetable Center in Taiwan has almost 60,000 seed samples from over 150 countries and focuses on food production throughout Asia, Africa and Central America. The International Center for Tropical Agriculture (ICIAT) in Colombia focuses on improving agriculture for small farmers, with 65,000 crop samples. Navdanya in Northern India has about 5,000 crop varieties of staples like rice, wheat, millet, kidney beans and medicinal plants native to India. They have established 111 seed banks in 17 Indian states.

Seed banks aren’t the only ways to preserve a seed. Botanical gardens could be called “living seed banks” where live plants and seeds are planted, studied, documented and preserved for future enjoyment and knowledge. Botanical gardens range from established and well-supported large city gardens to specialized and smaller scale efforts to preserve a single species or group of plants.

100 year old Native American corn in herbarium